AN INTERVIEW WITH DR. HILAL KAZAN A Contemporary Woman Master of the Pen

Dec 01, 2014 Interview

Hilal Kazan is a calligrapher who lives and works in Istanbul. In 2000, she received her ijaza in the thuluth and naskh scripts from Master Hasan Çelebi, one of the few calligraphers of the Republican period, and now has students of her own. Kazan, who has a Ph.D. in Islamic art history, is also a professor at Istanbul University and a published author in the field, having written, most notably, a book on Muslim women calligraphers. She has exhibited her work in many countries including Turkey, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, the United States, South Africa and the United Arab Emirates.

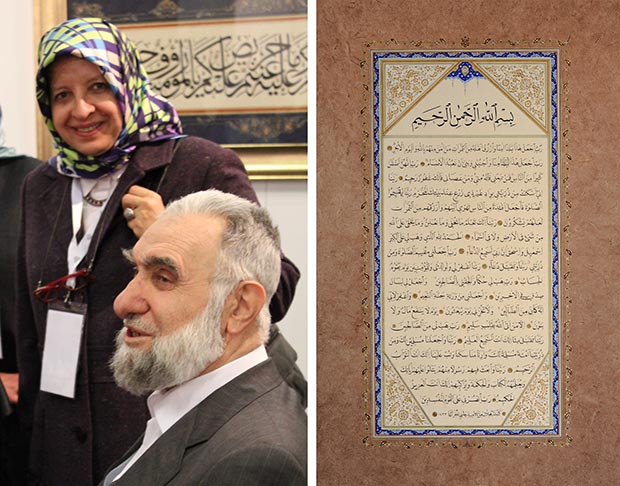

Left: Hilal Kazan with Hasan Çelebi / Right: Some prayers from Qur'an, naskh, 2012, 45x70 cm, coloured & sized paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

Left: Hilal Kazan with Hasan Çelebi / Right: Some prayers from Qur'an, naskh, 2012, 45x70 cm, coloured & sized paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

It was a great honour for me to become his student. He was one of the first calligraphers who received an ijaza in Ottoman calligraphy during the Republican period of Turkey. When I was an undergraduate student in the 1980s, I became interested in calligraphy and began to study mashk, a specific method in calligraphy, with the late Müşerref Çelebi. Müşerref Çelebi was both a calligrapher —she studied with the late Halim Özyazıcı— and a hafiz. However, since she was already very old, after a while, my practice with her was no longer efficient. Back then, I had heard that Hasan Çelebi was teaching but I didn’t know how to contact him. Later, a friend of mine introduced me to him and I started training with him from scratch, from the beginning again. Since then, I have been his student.

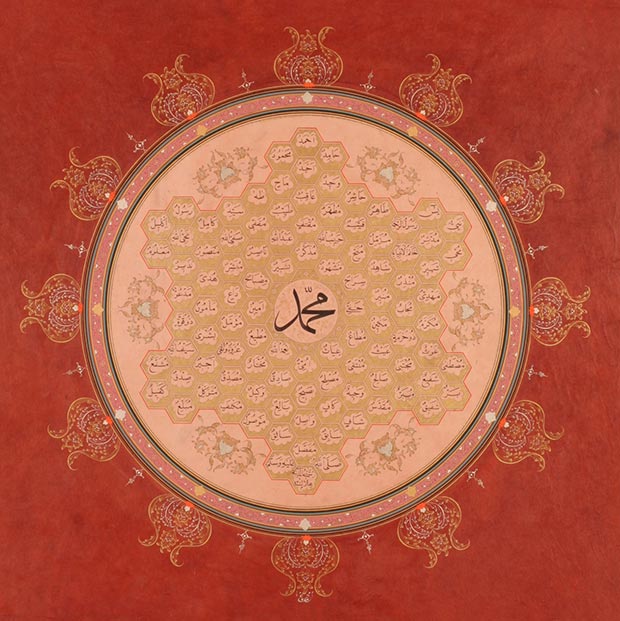

Hilal Kazan / Round Esma Nabi, thuluth & naskh, 2010, 70x70 cm, hand made & sized paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

Hilal Kazan / Round Esma Nabi, thuluth & naskh, 2010, 70x70 cm, hand made & sized paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

There is an idiom in the culture of the East: “No mashk can be without love.†To love what you are doing is one of the fundamental principles of being successful. It is very beneficial. One becomes more productive and successful in one’s work by loving it. It also enables patience and perseverance. That’s to say, you have to be patient in order to fulfill your goals. Once I aimed to learn the art of calligraphy for the sake of transmitting its culture to the next generations, it was calligraphy that attracted me to it and no longer the other way around. This is what we call in religious terms faid or “to be enlightened.†The intention no longer comes from the ego. Then the deep commitment of our masters to this art is transmitted to us.

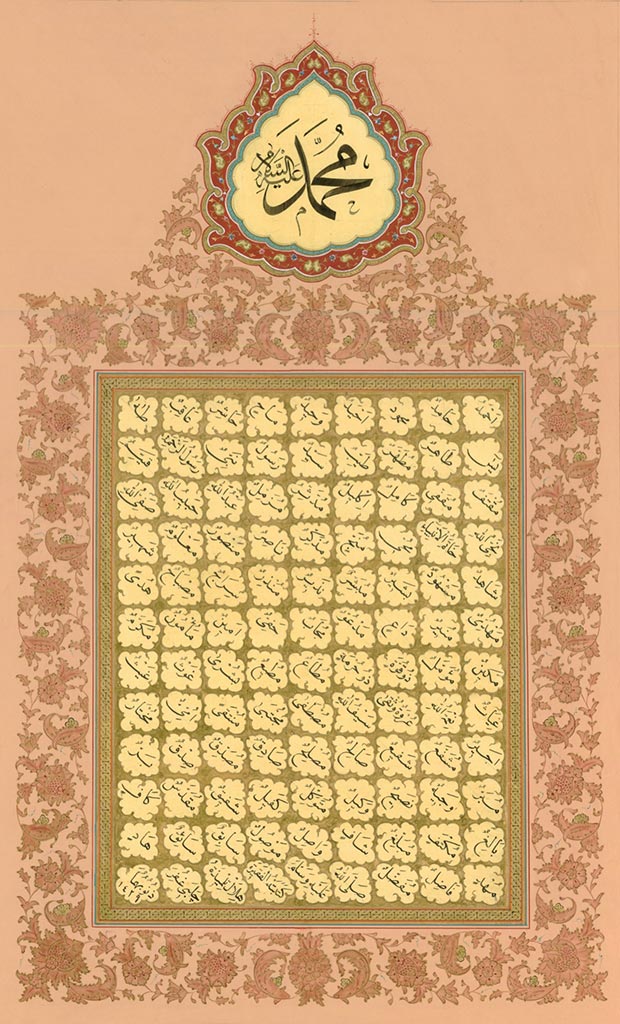

Hilal Kazan / Esma Nabi, thuluth & naskh, 2008, 45x75 cm, coloured & sized paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

Hilal Kazan / Esma Nabi, thuluth & naskh, 2008, 45x75 cm, coloured & sized paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

People who know me say that this art has contributed positively to my character. Generally, I am an impatient person who desires to finish things quickly. However, since I started to be occupied with this art, I have learned to move with life, accepting rather than fighting what it presents. In short, I have learned to be more patient. My view of life has changed too.

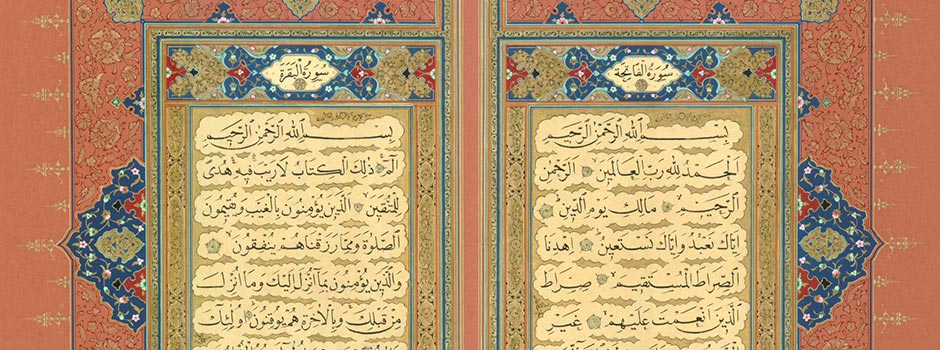

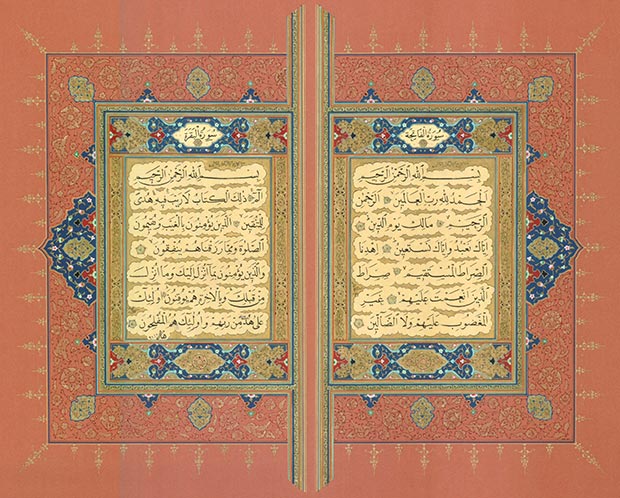

Hilal Kazan / First two pages of Qur'an, naskh, 2010, hand made old sized paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

Hilal Kazan / First two pages of Qur'an, naskh, 2010, hand made old sized paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

Throughout Islamic history, women have always been involved in the art of calligraphy. Even among them, some produced works as artistically powerful as men calligraphers and were called mardÄna, a Persian word that means ‘like a man’. There is only one difference between the genders. Because women calligraphers spent most of their time at home, they produced works that focused on the writing of the holy Qur’an, prayer books as well as calligraphic panels or levhas. In other words, they were not involved in calligraphy for architectural settings.

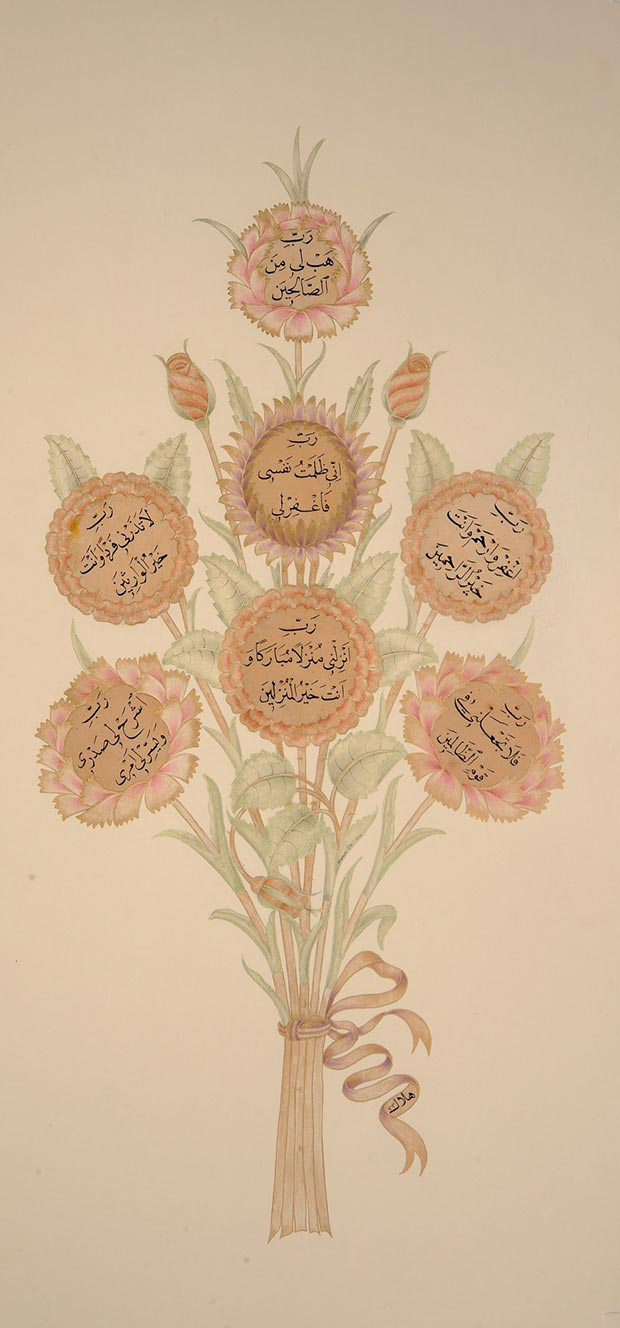

My disposition is to love writing in naskh, which is the script most often used for the Qur’an. The works that I have produced so far, I have designed myself. For instance, writing God’s most beautiful names, the asma’ al-husna, is a tradition for calligraphers. My Master in fact asked me to write the asma’ al-husna to obtain my ijaza. In addition to the asma’ al-husna, I wanted to write the Prophet’s most beautiful names, the asma’ al-nabi. I prepared a calligraphic panel with one hundred of the three hundred most beautiful names of the Prophet that I wrote in the same way as God’s most beautiful names are usually written. That’s to say, I prepared two identical panels, one of which is for God’s most beautiful names, and the other for the Prophet’s most beautiful names. Their styles of illumination and design were the same. Another work comes to mind too. Once we organized an exhibition called 'A Bouquet for Prayers' for which I wrote some prayer verses from the Qur’an in the manner of small circles. Then, I asked an illuminator who was very skilled in her job if she could illuminate my work in the manner of a bouquet. She illuminated it so that the verses were in the middle of a beautiful flower bouquet. People told me that my work was the most original one in that exhibition.

Hilal Kazan / A Bouquet of Prayers, naskh, 2012, 45x75 cm, hand made & sized old paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

Hilal Kazan / A Bouquet of Prayers, naskh, 2012, 45x75 cm, hand made & sized old paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

It is a different field of expertise. Each calligrapher has his or her own characteristics in writing just as that each of us has our own style of handwriting. Nevertheless, discerning them in artistic works entails more refinement. One who is not a calligrapher can learn to recognize or even produce the different styles of writing. Looking carefully and often at works produced in each style is also very important.

Hilal Kazan / Ism-i Nabi, Jali Diwani, 2012, 25x25 cm, coloured & sized paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

Hilal Kazan / Ism-i Nabi, Jali Diwani, 2012, 25x25 cm, coloured & sized paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

Hilal Kazan / Lafz-i Allah, Jali Diwani, 2012, 25x25 cm, coloured & sized paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

Hilal Kazan / Lafz-i Allah, Jali Diwani, 2012, 25x25 cm, coloured & sized paper, hand made/traditional ink / Courtesy of Hilal Kazan

I would rather thank you for giving me the opportunity to talk about my art. As both an artist and an academic, I always have a number of projects and things to do. As an artist, I want to produce some new calligraphic works. In terms of academic research, I am working nowadays on a long-term project dealing with women calligraphers in history. Hopefully, I will be able to finish it soon.

Comments

Add a comment