An Interview with Pakistani-American Calligrapher Sana Naveed An Islamic Calligrapher in Texas: The Art of Sana Naveed

Jan 03, 2013 FEATURE, Interview

Sana Naveed working on Masjid Al-Noor project / Courtesy of the Artist

Sana Naveed working on Masjid Al-Noor project / Courtesy of the Artist

Sana Naveed is becoming a much sought after calligrapher in North America. Born in Pakistan, she grew up on the west coast of Canada and presently resides in Texas with her husband and two sons. She lives a quiet life devoting herself to her family, spiritual practice and art. Born with a natural artistic ability, calligraphy chose her at the age of 14 and she has not looked back since, keeping her practice up while studying history at university, raising her sons, and now grappling with genetically inherited rheumatoid arthritis. She told me that the debilitating condition affecting her wrists but thankfully not her fingers has actually afforded her more focus in and for her work. Selling her work mostly by commission, she has recently completed her most challenging project yet, designing and executing monumental inscriptions and arabesque decoration for the Houston mosque Masjid Al-Noor.

'Ayat al Kursi' by Sana Naveed / 2010, 30x30 in, acrylic, inks / Courtesy of the Artist

'Ayat al Kursi' by Sana Naveed / 2010, 30x30 in, acrylic, inks / Courtesy of the Artist

Those who have commissioned work have been from all around the world, for example Saudi Arabia, England and the U.S. including my own city, Houston. While all definitely appreciate Islamic art, they come from all walks of life and not all are Muslim. I also work in conjunction with my sister Faryal, a graphic designer, helping design logos, book covers, and CD covers for groups such as the Burdah Ensemble and qawwali musicians like the famous Ustad Ghulam Farid Nizami.

Notice the spelling of the word which is not the way Orientalists write it. I grew up around traditional religious people who emphasized the love of the Prophet very much, so it was only natural for me to name my art in honor of him. Many Muslims believe that everything that Allah created is created from the Light of the Holy Prophet Muhammad and thus, as an artist whatever beauty I create is also inspired by his light. Referring to my work as Muhammadan art is also a way of rebuking certain forms of modernist Islam as a reminder that all good that comes to us in this life is because of Allah's love for His Beloved, through his blessings. Also I wanted to align my work with a higher ideal rather than with myself or my ego.

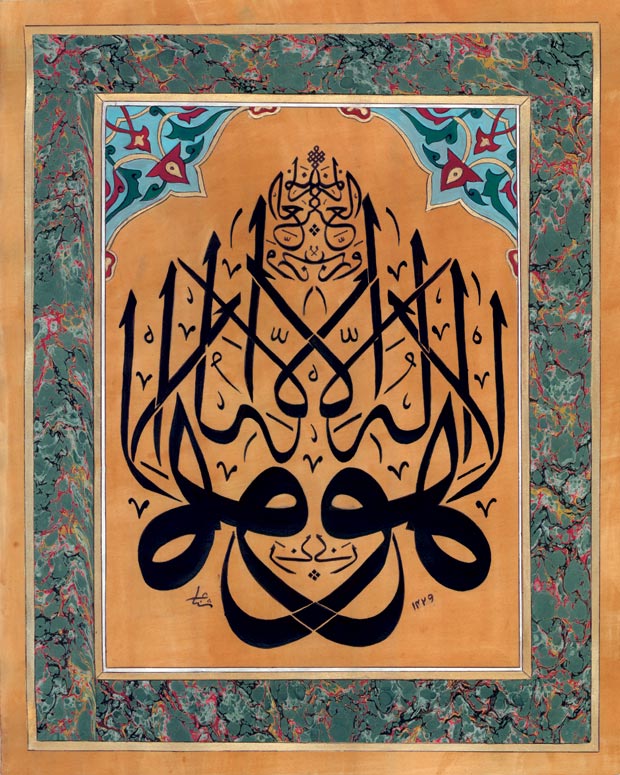

'La illaha illah Hu' by Sana Naveed / 2009, 11x14 in, acrylic ink, soot ink, on marbled/ tea dyed paper / Courtesy of the Artist

'La illaha illah Hu' by Sana Naveed / 2009, 11x14 in, acrylic ink, soot ink, on marbled/ tea dyed paper / Courtesy of the Artist

One's spiritual progress is definitely directly linked to one’s improvement in the art of calligraphy. It is a sacred art because it expresses mostly the words of the Holy Qur’an. It requires a great deal of patience and peacefulness within the heart. If the heart is restless or distracted, the outcome is sloppy... I find myself only doing well when I’m totally involved with mind, body and soul, otherwise the art will suffer. My Naqshbandi practices help me with this. It was once said that calligraphy is a mirror of the character and the straighter one could write the letter alif the more peaceful the soul. In other words, calligraphy is a skill whose steadiness of the hand reflects the soundness of the heart. Its sister art of illumination also requires a great degree of patience, faith, and reverence for the Holy words depicted.

To my great fortune, a very pious Muslim scholar, Shaykh Hisham Kabbani, visited Vancouver in the mid 1990s when I was about 14 years old and asked me to create a few calligraphy posters for an interfaith event. This is when my journey began. Ecstatic beyond belief but never having heard of Islamic calligraphy before, I went home that day and opened up an English calligraphy font book that I had and transformed the English calligraphy into Arabic calligraphy as best I could. At the event, the shaykh referred to one of my posters to bring up a point to the audience. This was not only an encouraging moment but also a defining one. The previously unknown world of Islamic calligraphy had just been opened up to me. I never looked back to other forms of art after that. It is kind of ironic now that I look back that I never was once told about this beautiful Islamic art form while attending the schools in Pakistan but was introduced to it in North America.

'Grandshaykh Abdullah's Tughra' by Sana Naveed / 2011, 24x18, Gouache paint, acrylic gold ink mixed with mica, soot ink on tea dyed paper / Courtesy of the Artist

'Grandshaykh Abdullah's Tughra' by Sana Naveed / 2011, 24x18, Gouache paint, acrylic gold ink mixed with mica, soot ink on tea dyed paper / Courtesy of the Artist

As I delved deeper into this art, my mother handed me a Syrian handbook of Islamic calligraphy that someone had given her as a gift shortly after my journey began. Once I got a hold of that book, I must have analyzed that book from front to back millions of times and what instantly attracted me was the cursive yet composed style known as thuluth. I focused on that one script and started copying the Arabic letters and even complex compositions with some bamboo pens from Pakistan. All I knew was that I must try to copy as closely as possible to the way the letters are formed in these masterful pieces. In the beginning, I used to just trace compositions and paint them in, then eventually I tried to write them myself and later started creating my own compositions by choosing simple names and phrases and ayahs from the Qur’an. Pasting the whole alphabet and all possible combination of letters on my drafting table and meticulously looking at each subtle detail of the forms, I started to get somewhat good so that other people started to appreciate what I was doing.

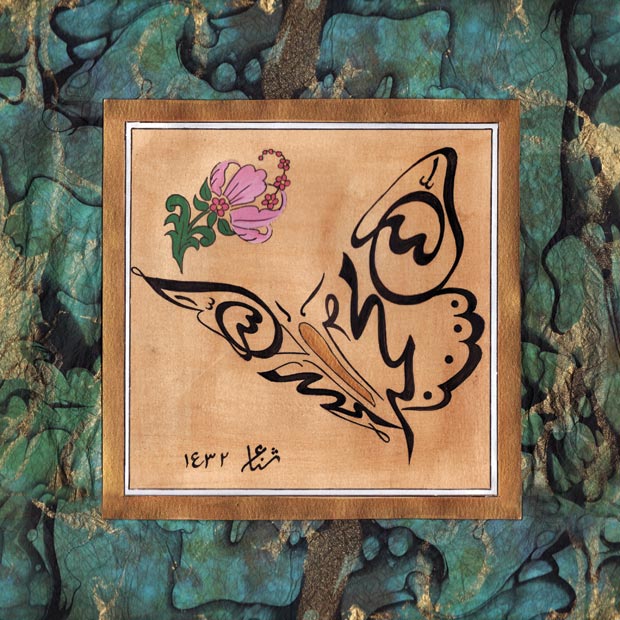

'The Butterfly of the Soul' by Sana Naveed / 2012, 10x10 in, tea dyed paper and soot ink / Courtesy of the Artist

'The Butterfly of the Soul' by Sana Naveed / 2012, 10x10 in, tea dyed paper and soot ink / Courtesy of the Artist

I wouldn't say that I'm really 'self taught' more along the lines of 'spiritually taught/guided'. Throughout my life I have always been blessed to be supported by many pious people. After many years of practising on my own though, I came across a roadblock in my progress. I was feeling that I needed an actual teacher to teach me the subtleties of the art that I was not noticing as well as technique. I contacted Mohamed Zakariya and shortly after he sent me the meskh of the basmala to copy and was impressed with my rendering of it, he invited me to visit him at his home in Virginia. I studied with him roughly for about a year but then the birth of my two sons and an unforeseen illness kept me from resuming. With hindsight, I think what impeded me was the difficulty of unlearning what I had done and starting over which is a definite requirement of learning calligraphy with a master. I hope one day to complete what I had started with such a masterful calligrapher that I was given the privilege to study with. Mohamed Zakariya definitely exposed me to Turkish Ottoman calligraphy and provided me with a glimpse of writing at a much more advanced level.

'Kalimah-at-Tawhid' by Sana Naveed / 2008, 24x30 in, acrylic ink, soot ink on tea dyed paper / Courtesy of the Artist

'Kalimah-at-Tawhid' by Sana Naveed / 2008, 24x30 in, acrylic ink, soot ink on tea dyed paper / Courtesy of the Artist

My approach has always been to copy the masters of which there are plenty. There is a lot of symmetry and nature is the Islamic art of illumination. My inspiration for the illumination comes from classical pieces as well as from architectural decoration and arabesque that gives the work a lot more boldness in detail and color. Although I admire the traditional methods of illumination and gilding, they require more resources and time than I have. I use watercolor for smaller pieces and acrylic for larger ones. When it comes to gold and silver, which is the main aspect of Islamic illumination, I've come across very effective metallic powders and mica to create a similar effect although I question the purity of it and hope to use all natural pigments one day.

'The Crown of All Good Deeds' by Sana Naveed / 2011, 23x12 in, Soot ink, acrylic inks, on tea dyed paper / Courtesy of the Artist

'The Crown of All Good Deeds' by Sana Naveed / 2011, 23x12 in, Soot ink, acrylic inks, on tea dyed paper / Courtesy of the Artist

I took on the Masjid Al-Noor project with a higher purpose in mind, namely to help foster awareness in Houston and America more generally of the beauty and spiritual ambiance that traditional Islamic art and calligraphy brings to a space of worship and to those who pray in it. The project was quite challenging due to its size, precisely 6 feet high and 95 feet in length. The mosque had initially chosen Surah Rahman for the dome but it was too long to fit in one single line so they selected the ayat al Kursi and two other ayahs from Surat al Tawba and Surat al Ahzab. It is painted with acrylic paints with the main color being reddish maroon with gold calligraphy and hints of light blue, olive green and black within the arabesque and border.

'The Dua of The Blind Man' by Sana Naveed / 2011, 43x28 in, Acrylic paint, mixed with mica for gold, tea dyed with soot ink / Courtesy of the Artist

'The Dua of The Blind Man' by Sana Naveed / 2011, 43x28 in, Acrylic paint, mixed with mica for gold, tea dyed with soot ink / Courtesy of the Artist

Well, first I composed and sketched out the calligraphy on graph paper on a much smaller scale then resized it as multiple templates that were transferred onto the painted panels with carbon paper, then painted the calligraphy with a straight edge curved brush similar to a kalam. The arabesque patterns will be blown up as well and made into a stencil to repeat the pattern more easily. I have divided the whole project into twenty four 3 by 5 foot panels for the calligraphy and another twenty five panels of the same size for the arabesque design that will be executed by making a series of stencils from my designs. In the end, each panel will be coated in varnish and mounted on a canvas cloth that will be rolled up and hopefully put up successfully by a professional wallpaper mounting company. The project required concentrated energy and many hours of it.

'Hadith of Knowledge and Guidance' by Sana Naveed / 2010, 10.5x8 in, acrylic inks / Courtesy of the Artist

'Hadith of Knowledge and Guidance' by Sana Naveed / 2010, 10.5x8 in, acrylic inks / Courtesy of the Artist

Pretty much throughout all my early teenage years I've suffered from this disease off and on, and as long as I can remember my wrists have become immobile. Not that I would wish this on anyone to progress in this art, but I will say that it has definitely changed my personality to better suit the practise of this art making me a more down to earth and more sober person. The stillness of my wrist allows for a much steadier hand that I probably would have needed many hours of practise to achieve.

Comments

Add a comment

Commenting is not available in this section entry.