AN INTERVIEW WITH SYRIAN MASTER CALLIGRAPHER KHALED AL SAAI Balance Between the Form of the Letters and an Aesthetic Harmony

Jan 29, 2015 Interview

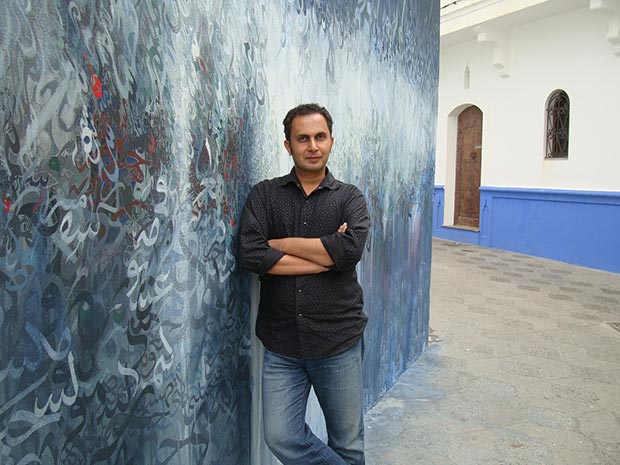

Khaled Al Saai was born in Syria in 1970. By the age of 18 he had already established a reputation as a calligrapher, going on to graduate from the University of Damascus in 1998 with his MA in Fine Art. Today, he is an internationally recognized master of Arabic calligraphy, and he works in an astonishing range of styles, from decorous classical modes to radically inventive compositions, in which lettering is fragmented into fantastical, almost pictorial compositions.Al Saai has received numerous prizes and awards in international festivals and calligraphy competitions, and his works can be found in the collections of the British Museum, UK, San Pedro Museum of Arts, Mexico, Denver Museum of Arts, Colorado, USA and Museum of Calligraphy, Sharjah, UAE among others.

Khaled Al Saai / Courtesy of the Artist and Kashya Hildebrand, London

Khaled Al Saai / Courtesy of the Artist and Kashya Hildebrand, London

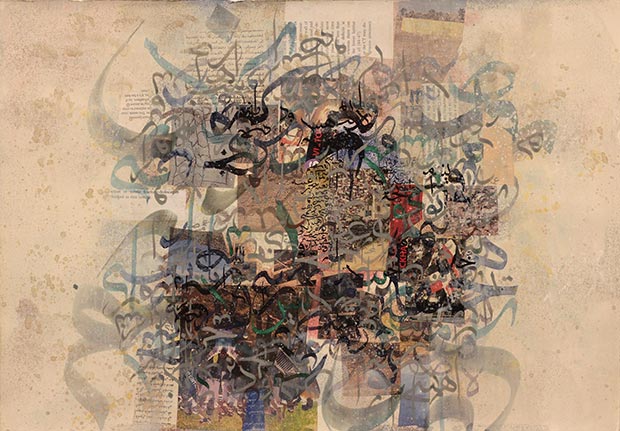

In the past, I have focused on the words themselves and their meaning, drawing on poetry andother literary sources. I have also worked with an expansive range of Arabic calligraphy styles. Now, however, I am trying to expand that range to include more elements, experimenting with collage or scale. Now, it is not just letters that play the main role in my works, but also other visual and metaphorical elements as well.

I grew up in a family that appreciated the arts, and I think that atmosphere drew my attention to calligraphy at a very early age. I was too young to figure out the meaning of the letters, but there was a visual attraction. Later, as an adult, I began to further appreciate the aesthetic value of Arabic calligraphy, and that in turn added more depth to my work. Basically, I work in the Thuluth script as well as the Ottoman DiwanyJaly style. The former allows for strong a composition and the latter brings softness and curved lines. I also feel that paper fits as a medium for traditional calligraphy (as opposed to canvas), which is why I stuck with it for so long. I’ve worked hard to get the same quality on canvas, and have now been able to achieve this.

Khaled Al Saai / Memory of City 1, 2014, 35x50 cm, mixed media and collage on paper / Courtesy of the Artist and Kashya Hildebrand, London

Khaled Al Saai / Memory of City 1, 2014, 35x50 cm, mixed media and collage on paper / Courtesy of the Artist and Kashya Hildebrand, London

At least in my case, yes, it is. The challenge is this: Traditional or classical calligraphy does not work well with the free strokes and fluidity of more modern forms, because there is accuracy to its ratios and rules. This has been my challenge, how to adapt the figures of letters and words to allow for an artistic vision and painterly atmosphere, while navigating the boundaries of classical calligraphy.

As a painter I have always admired the works of Rembrandt and Turner, because of the dramatic use of light in their works. I have even dedicated some of my painting to them, and colour gains its value and beauty from the presence of light. On the other hand, light plays another role in my work – that of a metaphorical one, drawing on my reading of Rumi, Kahlil Gibran and Sufi poetry.

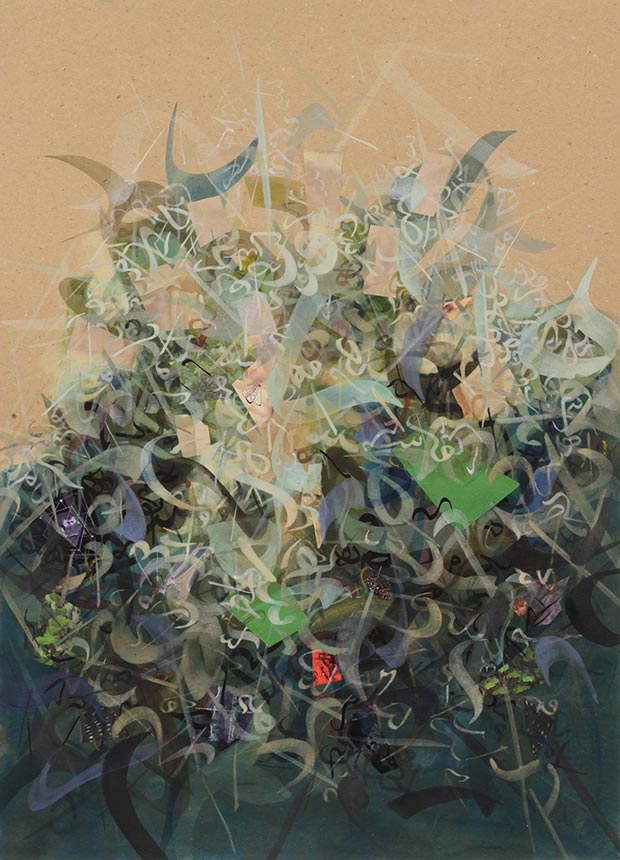

Khaled Al Saai / Untitled 4, 2014, 50x70 cm, mixed media and collage on paper / Courtesy of the Artist and Kashya Hildebrand, London

Khaled Al Saai / Untitled 4, 2014, 50x70 cm, mixed media and collage on paper / Courtesy of the Artist and Kashya Hildebrand, London

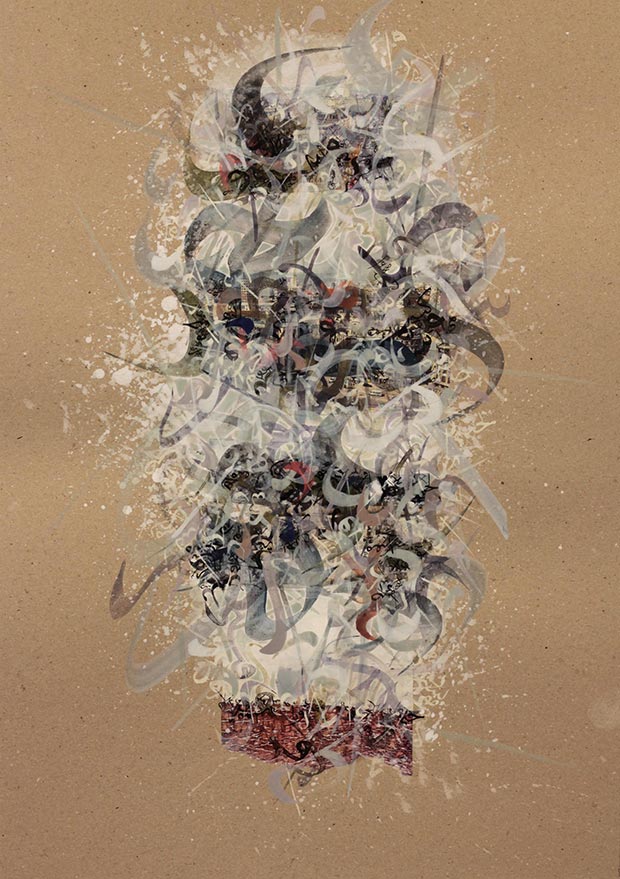

There has to be a balance between the form of the letters and an aesthetic harmony – each enhances the other. To paraphrase the Sufi poet Ibn Arabi, ‘letters are a nation among nations’. Therefore, I see letters as being alive, they have such a variety of shapes, they represent the human condition – they can breathe, be happy, sad, dance and express themselves. They have their own destiny.

I studied the history of European art while in university, so of course this has some measure of impact on the philosophy of my work. In the case of Arabic calligraphy, it will never be a purely abstract form; even a single letter indicates something by its shape. Furthermore, in Arabic, each letter has seven layers of representation. For example the letter ‘A’, or ‘alef’ in Arabic refers to God, as well as to the number one. On a figurative level, it represents the human being, as well as ideas of beginnings, unification, etc. All this background knowledge adds up and of course influences me, but, having said that, I have my own ideas of what each letter stands for and its symbolism, drawing on the interaction between fine art and Arabic calligraphy.

Khaled Al Saai / Untitled 9, 2014, 50x70 cm, mixed media and collage on paper / Courtesy of the Artist and Kashya Hildebrand, London

Khaled Al Saai / Untitled 9, 2014, 50x70 cm, mixed media and collage on paper / Courtesy of the Artist and Kashya Hildebrand, London

When working with traditional calligraphy methods, it is necessary to first treat the paper you are going to use. Not only does it have to be of the highest quality (preferably handmade), the treatment process both fixes the colour to the paper and ensures longevity along with allowing the brush to flow smoothly over its surface. Polishing the paper with a special stone completes the process. When working on canvas, on the other hand, I have to combine the technical aspects of calligraphy painting with those of ‘regular’ painting and it can be a struggle to translate the watercolour aesthetic and technique from paper onto a canvas. I’m pretty open to anything that will bring richness to my work, which is why I have started experimenting with pottery and collage.

These are two very different entities, and both should work for the sake of art and artists. Of course every artist dreams of a gallery or museum exhibition and the attention it brings. Art fairs, however, help to promote the work to a wider audience, so I think they each play a role.

This a big question! I think that calligraphy, within the realm of Islamic art, plays an important role. Meanwhile, many conceptual artists have made a name for themselves pushing the boundaries of what can be achieved, such as Susan Hefuna, or Kamal Boullata, for example. The increasing support and interest from international museums and art foundations is also encouraging.

Khaled Al Saai / Untitled 10, 2014, 50x70 cm, mixed media and collage on paper / Courtesy of the Artist and Kashya Hildebrand, London

Khaled Al Saai / Untitled 10, 2014, 50x70 cm, mixed media and collage on paper / Courtesy of the Artist and Kashya Hildebrand, London

The exhibition takes its name from one of the pieces on display, inspired by Damascus, where I spent many years. Damascus is a beautiful, intense city, one that to me holds the essence of the Orient, a city that forms the foundation of my personality. Damascus was a second home to me, and I loved the Barada river, all its beautiful views, as well as the people. Damascus was my own personal universe. The exhibition also has memories of my town, Mayadeen, where my family and my roots are, by the Euphrates, and where I made my first paintings and calligraphic works. Then there is my birthplace of Homs, that beautiful Syrian city. When I see now on television what has become of them all, I get so angry, it is so heartbreaking and impossible to witness these scenes of unbearable devastation. I collect newspaper images and use them in my collages, along with large, loud letters, trying to transform these scenes of anger and destruction into ones of beauty. It is to try to bring hope, a promise, a renewed faith in healing and new beginnings. Tragedy can be reversed if there is faith in a better tomorrow.

Khaled Al Saai / Inner Journey, 2014, 50x70 cm, mixed media on paper / Courtesy of the Artist and Kashya Hildebrand, London

Khaled Al Saai / Inner Journey, 2014, 50x70 cm, mixed media on paper / Courtesy of the Artist and Kashya Hildebrand, London

Most importantly is to keep working hard as usual, but I do have some ideas about working on a collection of work based on the concept of essence. I also have a museum show coming up in Mexico, and may be exhibiting my work as part of a big group exhibition on modernity in Arabic calligraphy in Europe next year. Hopefully I can also create an exhibition of my students’ works in the UAE or Gulf.

Thank you too for this opportunity, and to let me talk about my work. I hope it allows readers to get to know my art better, so thank you again.

Comments

Add a comment