INTERVIEW WITH NATHALIE BONDIL, DIRECTOR OF THE MONTREAL MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS From Spain to Morocco, Benjamin-Constant in His Time

Mar 22, 2015 Interview

Natalie Bondil, the director of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts / Photo © André Tremblay

Natalie Bondil, the director of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts / Photo © André Tremblay

Nathalie Bondil has been the Director of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts since 2007. Under her leadership, the museum has greatly expanded and its large exhibits have encountered increasing public success. It was she who initiated —along with Axel Hémery the director of the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse, France— the exhibit Marvels and Mirages of Orientalism: From Spain to Morocco, Benjamin-Constant in His Time.

Thanks to FRAME (French Regional American Museums Exchange), the show first opened in a first version directed by Hémery in Toulouse before travelling to Montreal in a second version directed by Bondil where it is currently on view. Its art historical importance lies in rediscovering an artist who, although famous in his day, has been largely forgotten since his death in 1902. Its contemporary cultural relevance is to be found in Benjamin-Constant’s Orientalist subject matter, which, if it provides visual interest, nonetheless displays and consolidates colonially-rooted stereotypes of the Muslim world. Bondil who specializes in 19th century art is keenly aware of the difficulty of disentangling the pictorial from the political in Orientalist art.

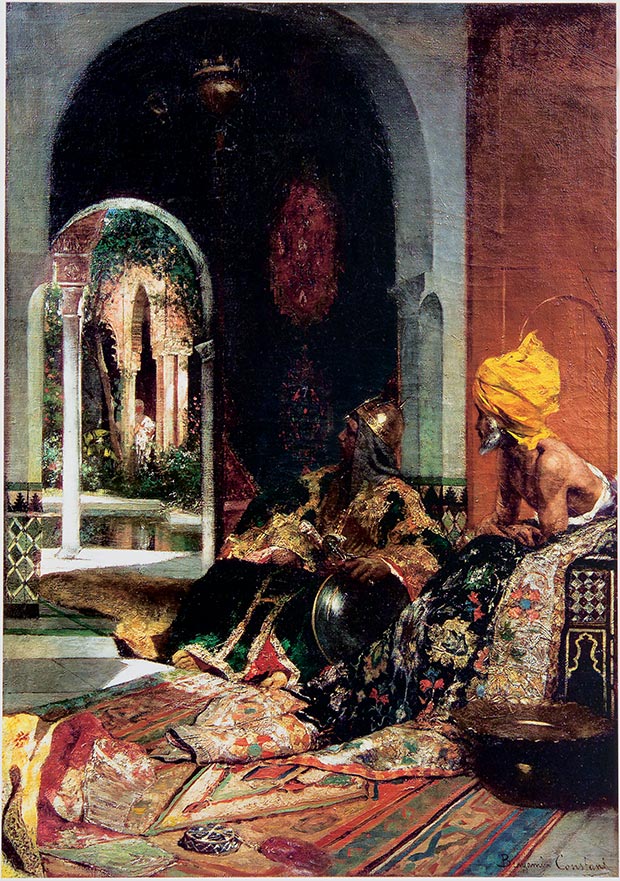

Cat. 134. TM / Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, In the Sultan’s Palace, N.d., Oil on canvas, 66x50.2 cm, Signed l.r.: Benj. Constant, Salt Lake City, Utah Museum of Fine, Arts, University of Utah, Gift of Mary P. Sandberg in honour of Mr. and Mrs. Henry H. Robinson / Inv. UMFA 1973.081.001

Cat. 134. TM / Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, In the Sultan’s Palace, N.d., Oil on canvas, 66x50.2 cm, Signed l.r.: Benj. Constant, Salt Lake City, Utah Museum of Fine, Arts, University of Utah, Gift of Mary P. Sandberg in honour of Mr. and Mrs. Henry H. Robinson / Inv. UMFA 1973.081.001

Benjamin-Constant championed himself as a very conservative painter. He fought openly against any kind of artistic modernity, especially the Realists and the Impressionists except for Puvis de Chavannes or Eugène Carrière. Even if in his early career from the 1870s through the 1890s his work was brilliant, he fell into a kind of facility with chic portraits and repetitive work. When he died rather young at 57, just after having painted Queen Victoria and the Pope, he was already an old-fashioned, although still powerful, ‘art star’. In 1900, the triumph of the «oculists» —using his words— remained a shame in his eyes.

He was naturally gifted, a superb colorist, a petit-bourgeois married into one of the most important French Republican families. He was a hard-worker who did not hesitate to explore America, a man of strict aesthetic principles, a fierce lobbyist for the Academy, and finally an ambitious dandy who enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle. He used his ostentatious studio like a reception salon, and from it sold his paintings to collectors from around the world. His corpus was forgotten with him, even if he had numerous paintings in museums collections and many international students at the Académie Julian in Paris.

Yes, his art was out of sync with the next generation of artists and painters. However, Benjamin-Constant’s career is especially interesting to study because it mirrors perfectly the major changes that occurred in the academic system during the French Third Republic in France (1870-1940). Profound changes emerged with the birth of artistic modernity such as a market for contemporary art, the professionalization of art —artists supported by art critics and art sold by dealers— and the rise of mass media and a consumer class. Simultaneously, the traditional state support of the Salon vanished. The state was the main buyer of historical or religious genre painting for churches and museums and the Salon the main venue for exhibits until the emergence of private galleries.

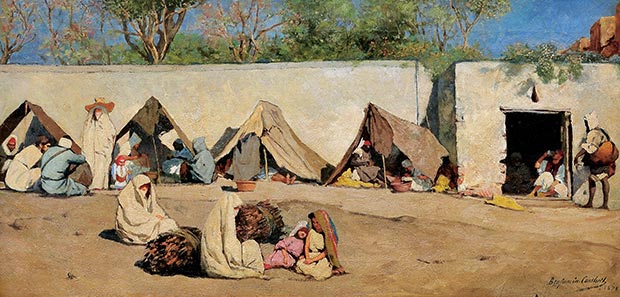

Cat. 165. M / Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, A North African Village, 1879, Oil on canvas, 70x100 cm, Signed and dated l.r.: Benjamin. Constant / .1879. / Collection Sami and Amina Zoghbi, Photo Hany Saïd

Cat. 165. M / Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, A North African Village, 1879, Oil on canvas, 70x100 cm, Signed and dated l.r.: Benjamin. Constant / .1879. / Collection Sami and Amina Zoghbi, Photo Hany Saïd

Even if official painters, like Benjamin-Constant, stayed attached to this old-fashioned system, they had to survive and sell. The investment costs of monumental canvases were huge for a single artist: renting a studio, buying the materials, paying the models, etc. Moreover, the paintings kept increasing in size because every painter wanted his work noticed amidst the thousands of paintings hung in the Parisian Salon. But the state market was too narrow for the number of paintings. This is why Benjamin-Constant like others explored other markets like those of monumental decorative paintings for the Republican regime’s numerous architectural projects, commissioned portraits, and those of foreign countries like England and especially America. Benjamin-Constant travelled many times to the States and even to Canada where he met with collectors and his New York dealer and painted their portraits.

I should add that, even if the Realist and the Impressionist movements were increasingly appreciated by the public —the smaller sizes were more suitable for private homes, the growing bourgeoisie had a new taste for realistic genre scenes among and for art speculation—, crowds preferred the spectacular "masterpieces" shown at the Salon, which catered to their taste for illusionism, akin to theater set decoration at the time with immersive panoramas anticipating blockbuster cinema. Those Salon paintings were thought to be windows on to other realities offering exoticism, Orientalism, nudity: seductive, shocking, impressive, popular, engaging, emotional in a positive way, these works were veritable "tours de force"!

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts already had two superb paintings by Benjamin-Constant when we recently received a donation of two others. As a curator specialized in 19th-century art, I was amazed because I could not find anything on this artist during the research made for our acquisition reports despite the numerous connections he had with Canada and America. After meeting Axel Hémery, director of the Augustins Museum in Toulouse —the city of Benjamin-Constant— which owns a great collection of Orientalist paintings, we decided to produce a show together.

Obviously the intense research done during these years, with the great help of our assistant curator Samuel Montiège, will finally shed light on this famous-but-unknown artist whose name appears regularly in auction or scholarship. The exhaustive catalogue I edited now constitutes the cornerstone of knowledge about Benjamin-Constant and his work as nothing had been published about him since his death with the exception of Régine Cardis’ 1985 unpublished thesis. The international scientific team I brought together for the catalogue brings new and diverse perspectives on Benjamin-Constant: it is totally a first. Wherever he is now, I hope Benjamin-Constant is happy with this kind of resurrection!

Cat. 160. / Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, The Watchful Guard, N.d., Oil on canvas, 45.7x31.8 cm, Signed l.r.: Benj-Constant, New York, Christie’s, October 24, 2007, lot 1 / Photo © Christie's Images / The Bridgeman Art Library

Cat. 160. / Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, The Watchful Guard, N.d., Oil on canvas, 45.7x31.8 cm, Signed l.r.: Benj-Constant, New York, Christie’s, October 24, 2007, lot 1 / Photo © Christie's Images / The Bridgeman Art Library

Looking for his works was a kind of treasure hunt for the curatorial team throughout Europe and America, even Africa with Egypt where works were located but impossible to ship, Algeria where we discovered a beautiful painting of Tangiers’ Sokko in the Algiers’ Museum and Morocco where we secured a great loan from a bank collection. We combed French and American museum collections, and have brought all these paintings together for the first time.

Institutions have invested in major conservation campaigns to save these immense, fabulous Salon paintings long forgotten in storage; this is the reason why we were able to get them as otherwise they would not have been able to travel. The exhibit is a unique occasion to discover them for the first time; the result is spectacular! More difficult was to locate the numerous paintings in private collections. I made the decision to publish a large majority of works sold in auction as the catalogue will undoubtedly remain the sole monograph for some time. It was a good idea one because every week people are contacting us to inform us of the locations of works that I only knew through catalogue illustrations.

There were no archives or family archives, or very few, except for ones we have just discovered thanks to the exhibition belonging to a less known branch of Benjamin-Constant’s family. We were like detectives scouring all kinds of information from different sources from national archives to eBay where were we bought many prints, postcards and photographs! We now have a little Benjamin-Constant archives’ fund at the museum.

Benjamin-Constant’s Orientalist corpus is mostly inspired by his trips to Morocco. Not many painters travelled there then, because this independent country was considered wild, dangerous, and therefore fascinating. Many French artists visited Algeria, which became a French colony in 1830, but few had the opportunity to see the “Land of the Farthest Setting Sunâ€, one of the rare countries of the Maghreb to have remained untouched by Ottoman influence.

Of those artists who did make it to Morocco, many went to Tangiers, historically a more cosmopolitan city, but few travelled to Marrakech like Benjamin-Constant. There is a striking parallel between Delacroix’s journeys in 1832 and Benjamin- Constant’s in 1871-1873. Both were guests in the context of diplomatic missions as France sought to secure Morocco’s neutrality in regard to Algeria. Leaving Tangiers, both artists found themselves in a country considered dangerous for foreigners. Their canvases express their fascination with this still little known area of the world. If Delacroix’s work exudes more empathy, Benjamin-Constant’s is characterized by its sensationalism and monumentality.

He can only be compared to his companion, the painter Georges Clairin but, unfortunately, the scholarship about this other famous-but-unknown academic artist remembered especially for his portraits of the actress Sarah Bernhardt, is also still lacking. Benjamin-Constant remains a superb ultra-colorist with a strong postromantic style, and a special gift for rendering the contrast of light and shadow. I also want to mention the case of the interesting former French “Moroccan†artist, Alfred Dehodencq whose work, although also monumental and sensationalist, was nonetheless on a smaller scale than Benjamin-Constant’s. Maria Fortuny and Henry Regnault, were only rediscovered recently by art historians because they were precocious artists who died young. They were influential for their decorative, glittering palette, stylistically more Moorish than Moroccan, so more modern. Maybe Benjamin-Constant, like Dehodencq or Clairin, embodies the weight of our Western guilt with his more theatrical and colonialist vision of Morocco, and maybe this is why they had remained mainly forgotten. But I was interested to notice in discussing with Moroccan collectors, that Benjamin-Constant’s art is now appreciated for what it is, and not for what we project.

Cat. 157. / Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, The Carpet Seller, N.d., Oil on canvas, 91x64 cm, Signed l.r.: Benjamin Constant, Paris, Aguttes, April 9, 2004, lot 130

Cat. 157. / Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, The Carpet Seller, N.d., Oil on canvas, 91x64 cm, Signed l.r.: Benjamin Constant, Paris, Aguttes, April 9, 2004, lot 130

As there is no evidence about Benjamin-Constant having assistants, I remain astounded by his intensive production, especially the huge canvases which required a lot of self-confidence and rapidity. 'The Harem' that is about 5x4 meters is the biggest picture we have ever introduced in our museum in one piece and not rolled, a true challenge for logistics. This huge work beautifully shows his quick brushwork, often working in impasto. Not a draftsman – only a few drawings are known —Benjamin-Constant is the master of effect with efficient geometrical compositions— very much in the style of his friend from the bright and virile artistic circle of "Les Toulousains" like Jean-Paul Laurens. His successful dramatic perspectives using monumental architecture such as main city entrances, impressive arches, stocky colonnades, for placing his figures evokes theatre set design, especially that of Victorien Sardou. In a less kitsch manner, Benjamin-Constant also plays with radical chiaroscuro and close-ups of larger-than-life figures. If his female models remain more standardized following Western taste, usually white-skinned with red hair, —which may be explained by repetition— we are seduced by some of his more authentic male portraits like the masterpiece Caïd Tahamy or a little jewel in a private collection, a Moorish Head.

In sum, Benjamin-Constant makes the balance among a clear palette inspired by his trips to Morocco, the depth of blacks from Rembrandt, and the colorful vividness from Delacroix, his two main masters. His facility to create such a decorative atmosphere or striking imagery explains that he was sometimes criticized for privileging aesthetics and composition over the people portrayed, but it is the work’s aesthetic sense that is exactly what we appreciate now. Benjamin-Constant’s style fits more in the context of the British Aesthetic movement where the exemplum virtutis dogma and the concept of painting as cosa mentale were not so much a strict academic principle. This is why he was so much appreciated there.

Cat. 156. / Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, Harem Women, N.d., Oil on wood, 124.4x80 cm, Signed l.r.: Benj.Constant, New York, Christie’s, October 24, 2007, lot 29 / Photo © Christie's Images / The Bridgeman Art Library

Cat. 156. / Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, Harem Women, N.d., Oil on wood, 124.4x80 cm, Signed l.r.: Benj.Constant, New York, Christie’s, October 24, 2007, lot 29 / Photo © Christie's Images / The Bridgeman Art Library

I am passionate about social history and especially the process of building iconographical identity - propaganda images, political artistic goals - as shown in several recent exhibitions I initiated or curated from 'Cuba ! Art and History from 1868 to Nowadays' in 2008, through 'Peru: Kingdoms of the Sun and the Moon' directed in 2012 to "Western": 'Mythology and Myths in Art and Cinema' scheduled 2017. Images are never innocent. Obviously, working on Benjamin-Constant was interesting for the scholarly rediscovery of his life and work. However, the main reason of the show for me was the opportunity to see beyond the art and engage with its social, colonial and gender dimensions… not yet much accepted in the French traditional art world. Trained in France, I remember gender studies were not part of our curriculum, contrary of Canada where I discovered multiculturalism: as a cultural hub crossing cultures between America and Europe, and now with a cosmopolitan immigration, Quebec is sometimes agitated… but so stimulating. So the goal was different than in Toulouse, where Axel Hémery’s exhibit used a more classic and neutral approach to emphasize the art of the city’s prodigal son.

In Montreal, I wanted to propose a complete different narrative with Said, Nochlin and others in the back of my mind. American postcolonial scholars have been of course translated into French for many years, but the examination of their legacy is not widespread in our more conservative education. Our recent colonial past in France also explains this relative timidity, despite major interesting institutions like the Institut du Monde Arabe, the Cité de l’Immigration, the Musée des Arts Premiers in Paris,the Musée de la Méditerranée in Marseille or the Musée des Confluences in Lyon. The subject remains still touchy, and I must say I was a little bit surprised showing that I am well adapted to my new country. This is why I invited rare French voices to write catalogue essays like Florence Hudowickz - whose project on the Musée de l’Algérie in Montpellier has been indefinitely postponed, despite strong criticisms, or like the feminist Christelle Taraud, not forgetting the inclusion of contemporary Moroccan artists.

And even more dollars now! Erwin Panofsky’s distinction between examining a work of art as "document" and as "monument" is here useful. Orientalist works are documents that can be interpreted through so many filters. I am convinced that art speaks many languages and that art historians do not have the monopoly of its interpretation. We learn so much by crossing our expertise with scholars from other disciplines. Orientalist art was made by white artists for white customers, mainly men. This is why we cannot avoid the colonial and male context of the genre, without excluding the standard stylistic art historical approach. Each perspective adds to our global knowledge of the work. Orientalism is such a wide subject as a Western construction because they are so many Orients. This is why I choose to focus on smaller, specific themes relevant to Benjamin-Constant and his circles in the exhibition: Byzantium at the Salon, Islamic Spain, Morocco, and the inevitable harem theme. Each possesses its own imagery and iconography with its fake mythologies or authentic testimonies.

As "monument", Orientalist art is variously appreciated throughout Arabic collections. Qatar recently acquired many works building a strong collection for their museum, the King of Morocco also owns many good Orientalists paintings some signed by Benjamin-Constant. These collectors can appreciate the works for what they are: superb paintings showing a reflection, sometimes distorted, of their past. But I do not think this kind of fine arts taste is spread throughout the population who has been exposed to Western clichés more through popular culture or entertainment like postcards or cinema.

Cat. 170. / Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, The Tailor’s Shop, 1878, Oil on canvas, 64x 100.5 cm, Signed and dated l.l.: Benjamin. Constant. 1878, New York, Christie’s, October 27, 2004, lot 54 / Photo © Christie's Images / The Bridgeman Art Library

Cat. 170. / Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, The Tailor’s Shop, 1878, Oil on canvas, 64x 100.5 cm, Signed and dated l.l.: Benjamin. Constant. 1878, New York, Christie’s, October 27, 2004, lot 54 / Photo © Christie's Images / The Bridgeman Art Library

From the very beginning, especially in light of the well-known harem motif and Fatima Mernissi’s books, it was obvious that I must include Middle Eastern contemporary women artists. Phallocratic, artificial, sugar sweet, and somehow disturbing iconic pictures by Benjamin-Constant’s companions —Debat-Ponsan, Gêrome, or Leconte de Nouy— often relate to the Ottoman world. Bringing in Moroccan women artists was more relevant regarding Benjamin-Constant as Bouziane, Essaydi, and Khattari, work precisely with Moroccan cultural iconography. Khattari, for example, has been directly inspired by Benjamin-Constant’s Cherifas whose huge painting is displayed along with her photographs in a very impressive face-to-face.

I am conscious that their contemporary stage is larger. I could have considered others artists like Fatima Mazmouz or Safaa Erruas. But it would be another exhibition, one, by the way, I would like to do one day about contemporary women Middle Eastern artists! I am convinced that mixing those works, from yesterday and today, is an absolutely necessary tool that helps us to understand and so to better appreciate each other’s artistic expression.

Comments

Add a comment