INTERVIEW Iranian Artist Ghazel Wins Prestigious French Government Award

Dec 21, 2018 FEATURE, Interview

Left: Portrait of Ghazel / Right: Ghazel, Black Hole Performance, 2011-12, Both photographs reproduced with the kind permission of the artist

Left: Portrait of Ghazel / Right: Ghazel, Black Hole Performance, 2011-12, Both photographs reproduced with the kind permission of the artist

Mrs. Catherine Grenier, Director of the Giacometti Foundation, presented Iranian artist Ghazel with the medal of the Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters at Paris' Museum of Immigration. 2018 has been indeed a very "ghazel" year. Not only because the artist had a solo show at Vienna's Hinterland gallery and participated in two group shows in Paris (Bic Foundation show at 104 Art Space, MAC Val-de-Marne), but also and especially because of the importance and timeliness of the issues the socially-engaged artist has been addressing for years. The fact that the French government has recognized my favourite art rebel's cultural contribution to France and the world has rekindled my faith that social justice and the politically incorrect sometimes win out in a still largely conventional art world.

Ghazel who lives between the "East" and the "West" is an inherently political artist. Her performances, videos, posters, and drawings tackle the topics of undocumented migrants and refugees, war, racism, East-West relations, and the politics of oil. Even her ongoing autobiographical "Me" series (1997-ongoing) that first garnered her international attention broaches oft-taboo subjects like the death penalty or state-sanctioned torture. Ghazel more than deserves the prestigious award because of the politics and compassion of her work, but also because of its tongue-in-cheek humour and anti-bravado aesthetic that both make art accessible and constitute a not-so-subtle critique of the art market.

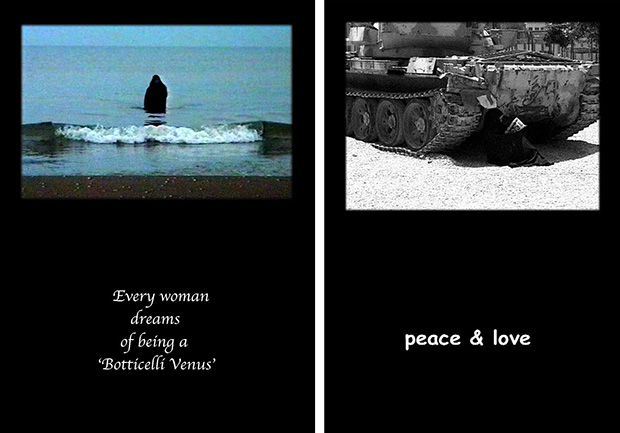

Left: Ghazel, “Venus” from “Me” series, video, (1997-2000). Right: Ghazel, “Tank” from “Me” series, video, (2000-2003) / Courtesy of the artist

Left: Ghazel, “Venus” from “Me” series, video, (1997-2000). Right: Ghazel, “Tank” from “Me” series, video, (2000-2003) / Courtesy of the artist

I received a letter on April 14. I was very surprised as I never expected anything like this ever. At first, however, I was kind of angry telling myself, “I don’t want to be just another chevalier.” But then I thought, no wait, it’s so nice because I was the black sheep of the artists of my generation. I’m really so very thrilled that the Ministry of Culture has followed my work, even if I haven’t shown much in France for the last four years. In short, I am really happy with the award. I am especially proud because I don’t have a powerful gallery in Paris or elsewhere in Europe that’s backing me.

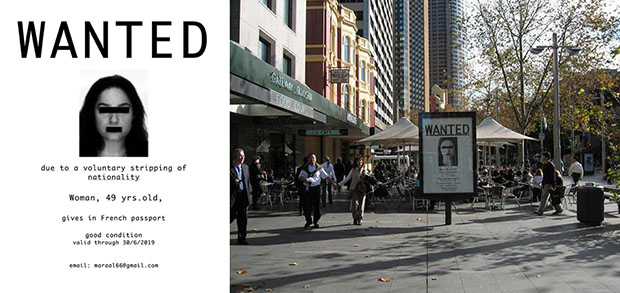

Left: Ghazel, “Wanted” poster, 2016. Photograph @ Ghazel. Right: “Wanted” Poster on view in Sydney, Australia, 2006. Photograph@Biennale of Sydney.

Left: Ghazel, “Wanted” poster, 2016. Photograph @ Ghazel. Right: “Wanted” Poster on view in Sydney, Australia, 2006. Photograph@Biennale of Sydney.

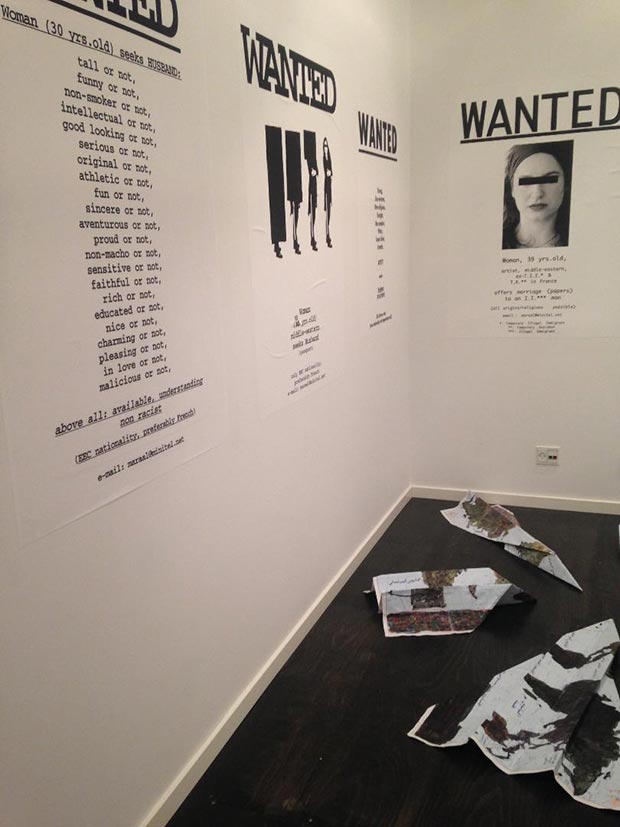

Yes, that’s what I think too. How cool and amazing it is, especially because two years ago, in 2016, I started bombarding everybody with my last poster in my “Wanted” series. It proposes a voluntary self-stripping of French nationalites as a reaction to ex-president Francois Hollande’s wish to strip Middle Eastern criminals or terrorists of their nationality even if they are second or third generation immigrants. For me, French is French, regardless. We don’t strip criminal actors of other ethnic origins of their citizenship. The “Wanted” work made in contestation to Hollande’s proposal led to a lot of heated discussions and debates with people —even friends— who couldn’t understand my perspective of not accepting select racism. This award, however, confirms that France is a country with a continued tradition of freedom of expression. I really appreciate the fact that it recognizes my work in spite of my critiques and political views.

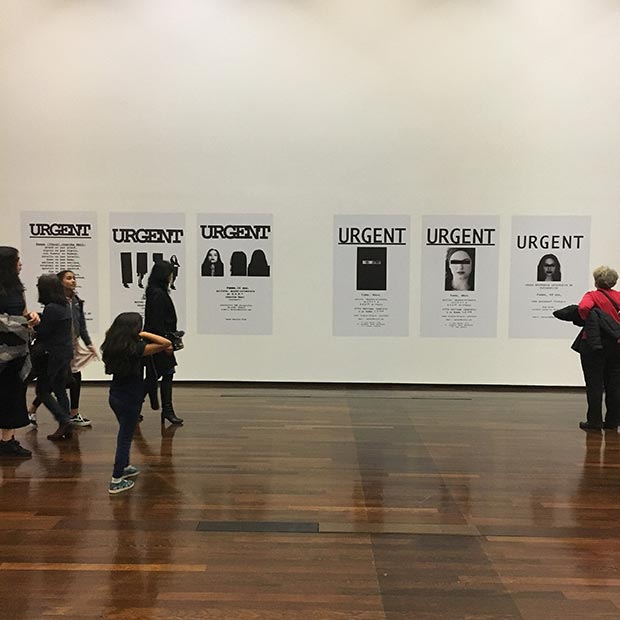

The Museum of Immigration has bought six of my “Wanted” posters or “Urgent” in French, four of which form part of the permanent collection. This pleases me a lot because it is a history museum and therefore visitors go to learn about history, not art. The posters are popular there and I am happy that they possess this additional important dimension of historical document. It’s because of the institution’s interesting work and the art collection that I chose the Parisian museum for my award ceremony. I am grateful to the whole team there.

Installation shot of Ghazel’s “Wanted/Urgent” posters at “Persona Grata ”exhibition, Val-de-Marne Contemporary Art Museum, 2018. Photograph @ Azad Asifovich

Installation shot of Ghazel’s “Wanted/Urgent” posters at “Persona Grata ”exhibition, Val-de-Marne Contemporary Art Museum, 2018. Photograph @ Azad Asifovich

Installation shot of Ghazel’s “Wanted” posters at “Deportation Regime: Artistic Responses to State Practices and Lived Experience of Forced Removal” exhibition (September 9 – December 16, 2016) at the Center for Art on Migration Politics in Copenhagen. Photograph @Ghazel

Installation shot of Ghazel’s “Wanted” posters at “Deportation Regime: Artistic Responses to State Practices and Lived Experience of Forced Removal” exhibition (September 9 – December 16, 2016) at the Center for Art on Migration Politics in Copenhagen. Photograph @Ghazel

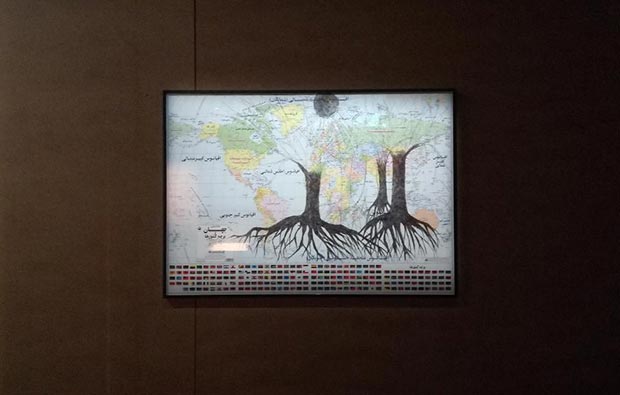

I showed a lot of new map drawings that comment on world politics and manmade disasters. In fact, I hung a huge map -2.88 cm high by 3,70 cm wide- that took up a whole wall. During the opening, I did a performance, blackening the map not with ballpoint pen like the drawings, but with acrylic paint.

Installation shot of "Dyslexia" exhibit at Hinterland Gallery, Vienna, 2018 / Courtesy of the artist

Installation shot of "Dyslexia" exhibit at Hinterland Gallery, Vienna, 2018 / Courtesy of the artist

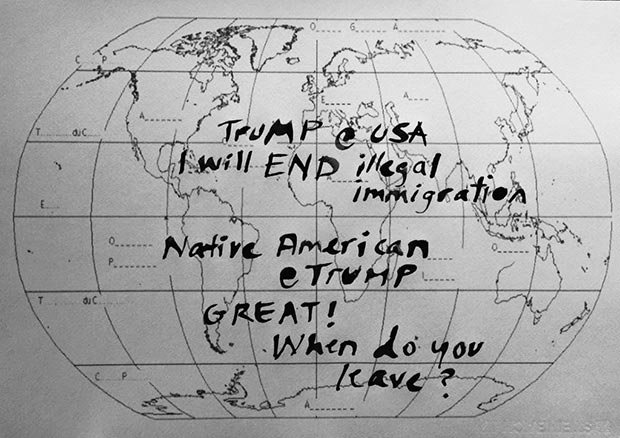

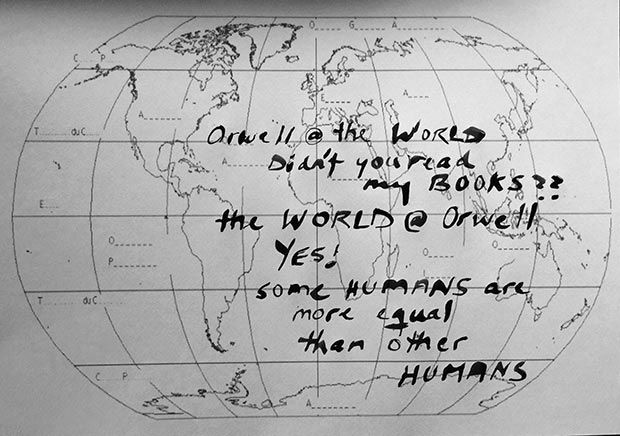

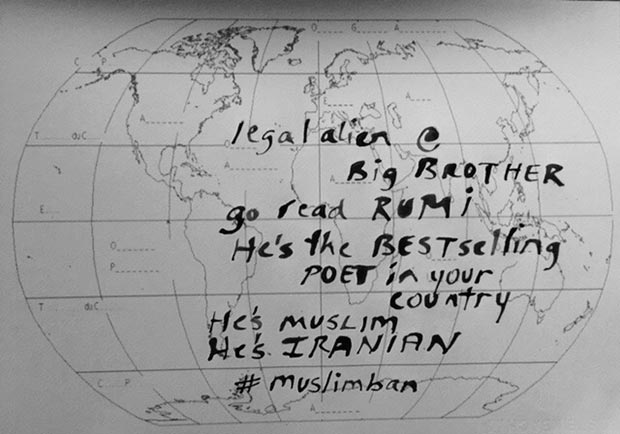

Yes, I showed this new series for the first times. They are hand-drawn ‘tweets’ or what I call ‘inputs’ addressing contemporary political issues like Trump’s wall or his disturbing views on migrants. These works are inspired directly from real tweets by political leaders like Hollande, Trump or Austria’s right-wing Chancellor Sebastien Kurz. A lot of Austrians were surprised that I would dare to comment on Austrian politics. However, I think that many people overlooked the tweets, not only due to their political content but also because they were not exhibited in the right way. I will, from now on, show them in black and white and as posters on larger paper and take them out into the streets and place them in strategic areas. For example, the one in which Hollande expresses his regret for the stripping of nationality idea and to which the late François Mittérand offers an imagined response will be placed in the Marais or Saint-Germain des Prés neighbourhoods of Paris. I am also going to transform the works into videos in which the tweets function as a metaphorical heartbeat. I’m really excited about the possibilities of this new project.

Ghazel, from the "Inputs" series, photocopy of ink on cardboard, 29.70 x 42 cm, 2017. Photograph @ ghazel

Ghazel, from the "Inputs" series, photocopy of ink on cardboard, 29.70 x 42 cm, 2017. Photograph @ ghazel

Ghazel, from the "Inputs" series, photocopy of ink on cardboard, 29.70 x 42 cm, 2017. Photograph @ ghazel

Ghazel, from the "Inputs" series, photocopy of ink on cardboard, 29.70 x 42 cm, 2017. Photograph @ ghazel

Ghazel, from the "Inputs" series, photocopy of ink on cardboard, 29.70 x 42 cm, 2017. Photograph @ ghazel

Ghazel, from the "Inputs" series, photocopy of ink on cardboard, 29.70 x 42 cm, 2017. Photograph @ ghazel

Actually, I first starting talking about undocumented migrants when I got an expulsion letter from the French police. I was really scared. The letter gave me fifteen days to leave the country, but it took five days to arrive, leaving me with only ten! I was able to become a student again to save myself from being deported. I had to do something with this experience that left me feeling uprooted and displaced. I no longer had a romantic vision of roots and belonging. In one moment, I had become one of those undocumented people you see on TV. It was a big slap and a turning point. It led to my ongoing “Wanted” poster series. When I got my resident card in 2002, I did one offering a marriage of convenience to an undocumented migrant and then I began working with real migrants in “Home Stories.” For the latter, I spent a few weeks outside of Venice giving workshops to migrants and this culminated in a performance by the participants around the theme of home in the 37th Venice International Theater Festival –and later into the film “Home (Stories).” It was the first time my social work and art were married. An Afghan migrant was supposed to take part in my first filmed “Road Movie” performances, but just before the first performance, he stood me up and asked me to do the performance myself. What he said to me to explain his change of heart was so moving, it became the heart of the performance. He said, “I don’t want to tell a story, a fiction and if I tell the truth, no one would believe me because they have seen too many films and will say my life is just another fiction story.”

_2008_01.jpg) Still from Ghazel's "Home (Stories)" 2008 / Courtesy of the artist

Still from Ghazel's "Home (Stories)" 2008 / Courtesy of the artist

_2008_02.jpg) Still from Ghazel's "Home (Stories)" 2008 / Courtesy of the artist

Still from Ghazel's "Home (Stories)" 2008 / Courtesy of the artist

The thing is that I find much contemporary art very boring; it has become, in my eyes, increasingly formalist, decorative or superficial. I mean, I’m not saying that this is the whole of contemporary art, but a lot of what we see and what is sold seems far from reality and real issues. This trend is seen not just at art fairs, but also at biennials and big exhibitions. My work doesn’t fit into this category of art that is politically correct and unconcerned with today's many problems. I’m proud that my work is socially conscious and engaged, and I admit that I have difficulties with the necessary commercialism of the art world. I left my gallery in Dubai this year because I can’t work with galleries anymore.

The context and the message are always more important than form in my work. This is largely due to my encounter with French Fluxus artist Robert Filiou’s “Bien fait, mal fait, pas fait” or “Well Done, Badly Done, Not Done” when I was a young student of 22 or 23 years old. I was amazed by this piece and, when I started to work seriously on my art after art school, I realized that I had to say what I had to say and that the form came after the concept or idea. It liberated me! I always make work in the simplest and direct manner without spending too much money or energy. If I can make a sculpture out of recycled aluminium, why make it out of bronze or copper? Moreover, I think when you work with recycled aluminium, there is something more important going on. There’s a better message then too. Before making any piece, I always also think of Duchamp’s words about thinking twice before adding another object to our object-laden world. In short, I make everything without make-up; that’s a conceptual aspect of my work. And I do everything myself —whether video, sculpture, drawing, etc.— without subcontracting it to keep a human dimension to it. The low-tech aspect creates a style.

Ghazel, "Life Span of a Ballpoint Pen" (ink on paper, 2010) at Bic Foundation show, 104 Art Space, Paris, 2018 / Courtesy of the artist

Ghazel, "Life Span of a Ballpoint Pen" (ink on paper, 2010) at Bic Foundation show, 104 Art Space, Paris, 2018 / Courtesy of the artist

In 2010, I returned to drawing that I find meditative. I think it came to counterbalance the eight or nine years spent exclusively on my ongoing video series “Me.” I spontaneously began drawing on world maps, which had appeared in “Me” videos as fans, a toreador’s cape and so on. During the first drawing, my Bic pen ran out and I left it as such. This is the work that the Bic Foundation bought. It was exhibited in the show alongside four maps from the “Dyslexia” series that they borrowed.

The show was really interesting because everyone can relate to a Bic pen. The ballpoint pen was a fabulous invention and Bic remains one of the most popular pens on the globe. And so besides there being great artists in the show like Giacometti and Boetti, the most interesting thing for me were the viewers and how engaged they were. Many visitors, for instance, drew in the guest book in addition to leaving comments. I’ve never seen viewers so involved in an art show. After all, a Bic pen is not a mystery and everyone can use it.

Comments

Add a comment