INTERVIEW Islamic Calligraphy Art by Nuria Garcia Masip

Jul 09, 2017 Interview

This article is a part of the project 'Promotion of the Ottoman Cultural Heritage of Bosnia and Turkey' which is organized by Monolit, Association for Promoting Islamic Arts and supported by the Republic of Turkey (YTB - T.C. BAŞBAKANLIK Yurtdışı Türkler ve Akraba Topluluklar Başkanlığı / Prime Ministry, Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities).

Nuria Garcia Masip with Dr Fatih Özkafa / Courtesy of Dr Fatih Özkafa

Nuria Garcia Masip with Dr Fatih Özkafa / Courtesy of Dr Fatih Özkafa

I first encountered calligraphy in Morocco in 1999 while I was exploring different Moroccan traditional arts and studying Arabic. In contrast to other mediums I loved the simplicity of the materials used in calligraphy --paper, ink and qalam-- and the discipline needed for its practice. Unfortunately at the time there were no trained calligraphers in Morocco, so this led me to look for a true master, starting my studies with master Mohamed Zakariya in the USA and later on in Istanbul with Masters Hasan Çelebi and Davut Bektas.

Of course one of the things that drew me towards calligraphy was the fact that it is so intimately linked to writing the sacred Word.

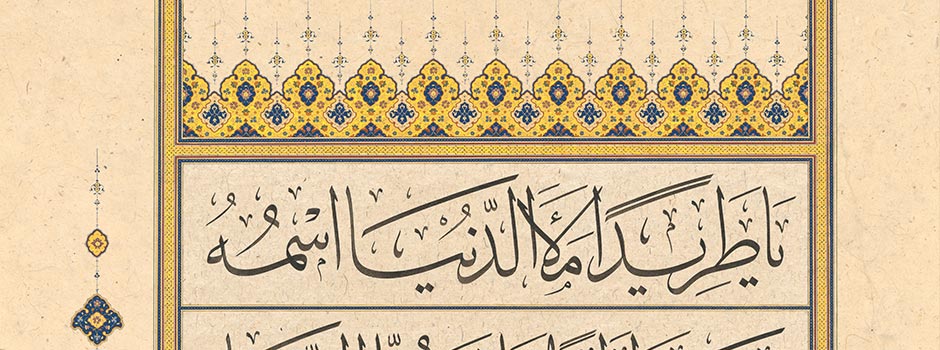

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

Like in any classical art, such as music, the discipline needed to become a calligrapher involves a lot of time, sacrifice and hard work. For me, I also had to travel to see my teachers, adapt to a new culture, learn Turkish… this involved major decisions and sacrifices which of course affected my personal and professional life. As you know the relationship with our teachers doesn’t end after obtaining the calligraphy diploma, or ijaza, so we invest our whole lives in the learning process. Calligraphy invades our whole existence; we think, breathe and dream about calligraphy. This of course can lead to forgetting other aspects of our lives so our challenge is to find a healthy balance.

When I first started studying calligraphy I had no idea whether I would be able to practice this art professionally, what drove me was my deep love and passion for the art. One of the biggest blessings has been to be able to dedicate myself to this art full time, to produce calligraphy pieces, and to transmit this art to others across the globe. Thanks to calligraphy I continue to learn a lot about myself and my limitations…

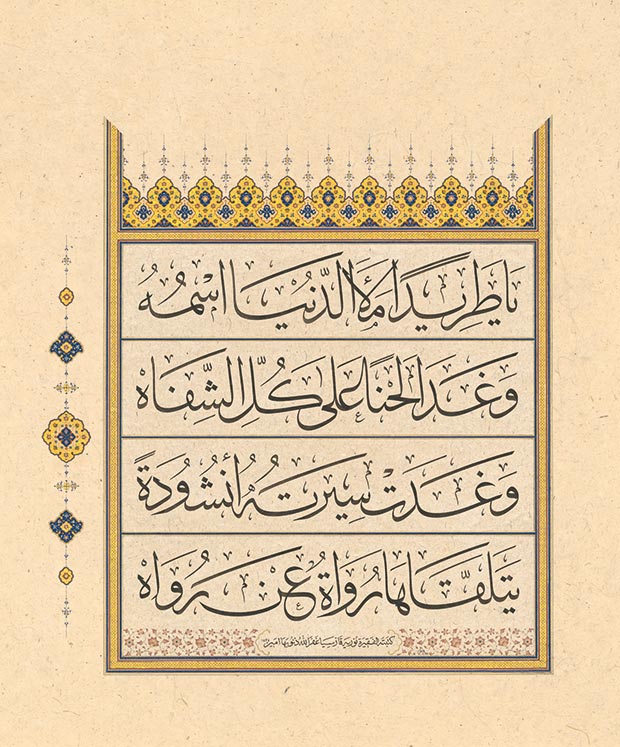

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip, Firdevs bakkal / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip, Firdevs bakkal / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

I should first mention that my teachers never made any distinction between their students and always treated everyone equally with utmost generosity. In most calligraphy classes there were always more women than men and the gender distinction was never an issue. There was of course a conservative social and cultural context where women and men tend to stay in separate groups, so it was up to us reach out and engage beyond these invisible lines.

The first time I felt the gender distinction was at a calligraphy exhibit in Istanbul where I realized that most of the pieces exhibited were done by men. So I think the gender issue starts when we start practising calligraphy professionally. Just like in other professions, as women we need to work harder to prove that we can compete on an equal basis and that the quality of our work is up to the standard. There are still a lot of patronising attitudes which tend to see women more as “scribes†than calligraphers, so it is up to us to break those stereotypes and be proactive about seeking knowledge and displaying our work. Thankfully there are also those who support us and have given us ample opportunities.

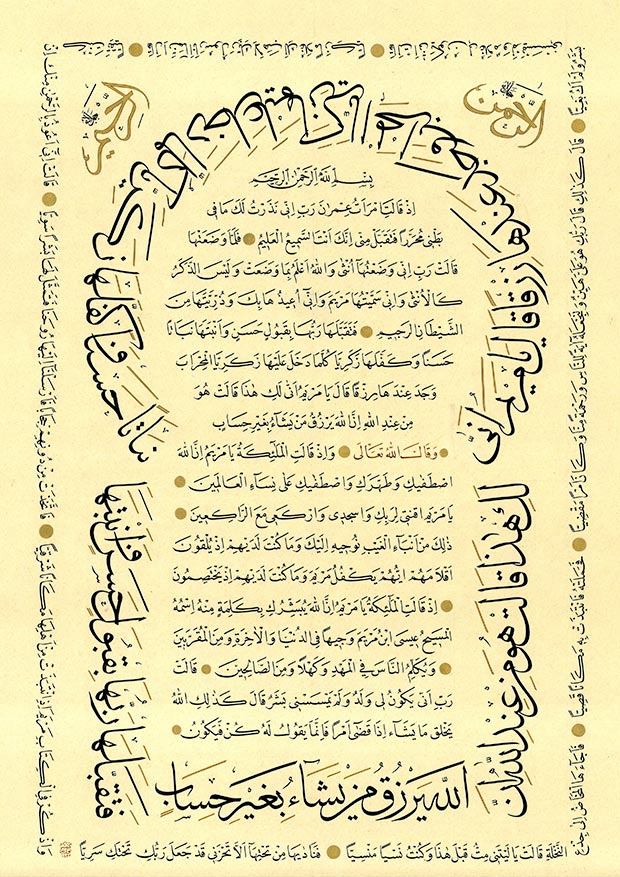

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip, Hazreti Maryam / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip, Hazreti Maryam / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

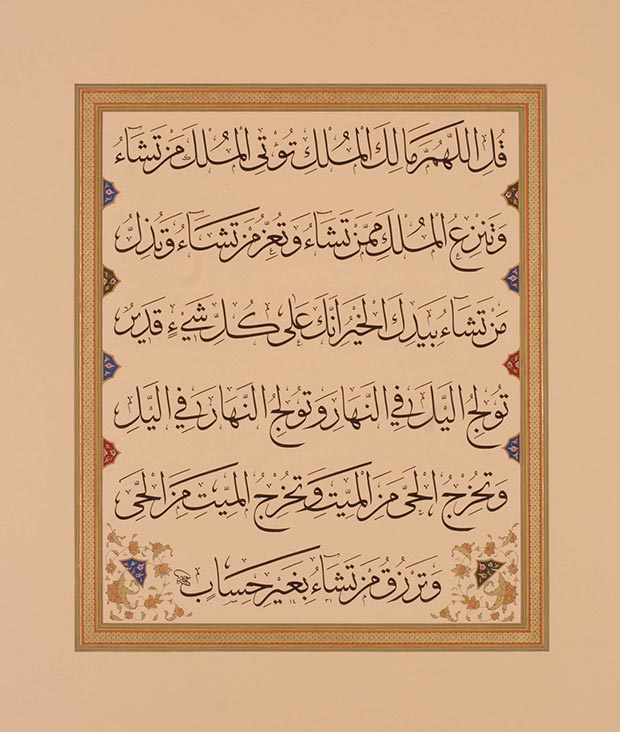

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip, Surah-Al-Imran, Thuluth / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip, Surah-Al-Imran, Thuluth / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

I think we need to make a distinction between classical calligraphy and contemporary/ modern calligraphy. When it comes to classical calligraphy I think the art has an ocean of depth and history that contains a myriad of aesthetic possibilities. It is up to us to continue this heritage in all its facets and styles and present it in the most beautiful way possible not confining ourselves to a couple of centuries but exploring the huge breath of the tradition.

For me the roots of calligraphy are in the materials –pen, ink and paper–, in the proportion and harmony of the letters, and in the strength of the hand’s gesture. When these elements are present I feel like the spirit of calligraphy is protected.

When it comes to contemporary/modern calligraphy (I use the term “modern†to emphasize the non-classical approach), as the term itself indicates, there are of course infinite possibilities. I personally prefer contemporary calligraphy which is still rooted in the original materials and that reflects a knowledge of calligraphy; even when the classical rules of proportion or form are broken we see the underlying structure of calligraphy in the gesture and movement of the strokes. I think the two categories, both classical and contemporary can co-exist as long as neither one tries to invade the other.

Finally it is worth noting that there are many contemporary visual artists using letters in their paintings or sculptures (what is known as the “houroufiya†school) with no knowledge of calligraphy. This is a different category altogether and I think we should avoid categorising them as calligraphers since it only leads to confusion.

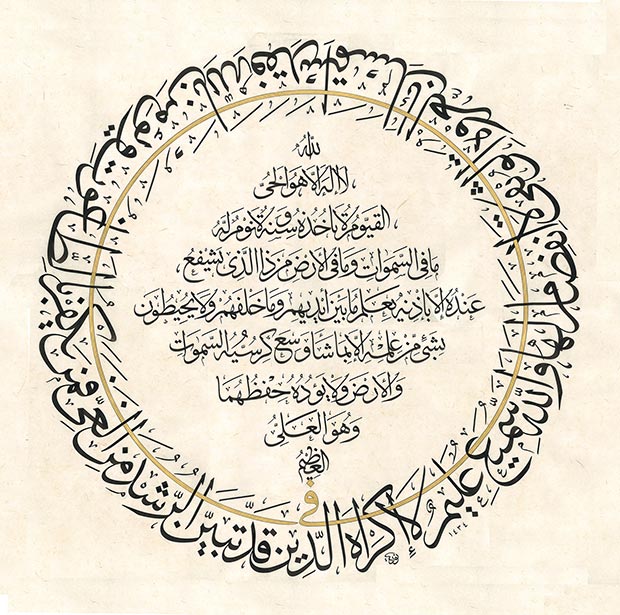

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

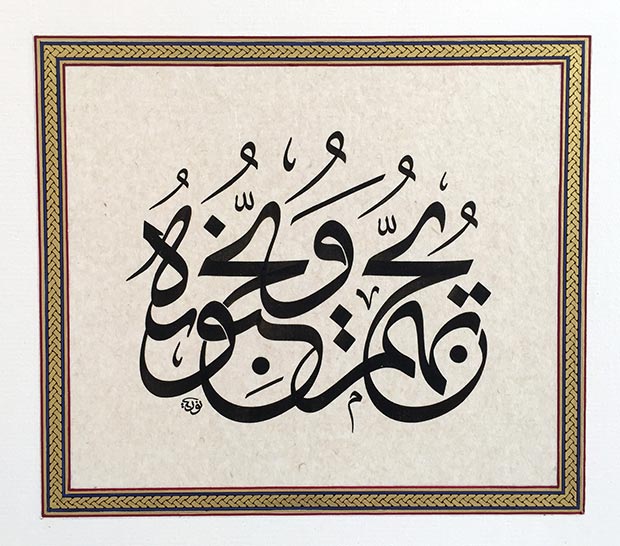

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip, Yuhibbuhum wa yuhibbunahum / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip, Yuhibbuhum wa yuhibbunahum / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

When I first started studying calligraphy my first teacher told me, “there are no shortcuts in calligraphyâ€, meaning one had to go through all the meÅŸks (lessons) in the curriculum in order to progress. Looking back at my own experience and as a teacher today, I think that if one wants to be a professional calligrapher this meÅŸk system is still the best way to study. As well as calligrapher one learns a lot of patience, self discipline and structure, which ultimately helps greatly in the practice of the art itself. However this doesn’t mean that it cannot be complemented with other tools and pedagogical techniques, and this is up to each teacher to develop.

Teaching calligraphy to students with very different backgrounds I find myself using a combination of methods in my classes and trying many different approaches. I think it is important to foment motivation and the love for the art.

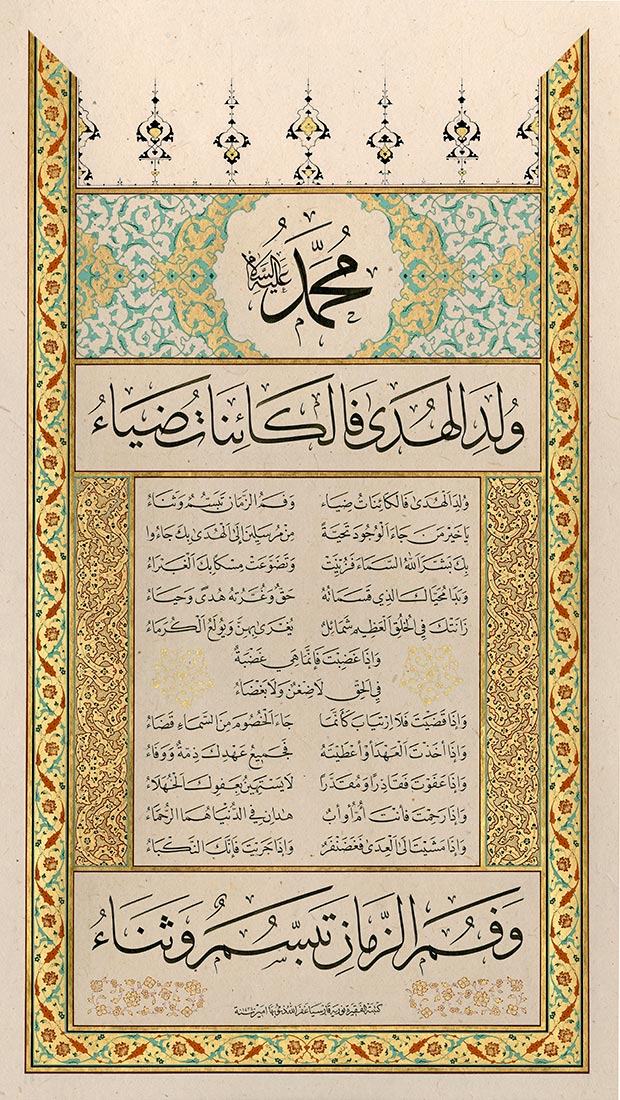

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip, Zerendud / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip, Zerendud / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

I think we see two tendencies in today’s world, on the one hand a digitalization of almost everything, and the dying out of many traditional art forms. On the other hand, a nostalgic tendency to go backwards in time and preserve what is being lost. In calligraphy I think at the moment we are experiencing the latter. There is a reaffirmation of local identity and religion which has made collectors in the Islamic world increasingly value and support Islamic art.

However when it comes to making this art known to the West I think we still have a lot of shortcomings. Mainly because as calligraphers living in Europe or the United States we do not have the support system, from the state or private, to do everything we would like to do in order to make this art more widely known. There is a lot misinformation, and it all comes down to individual effort and hard work. When I see what the Chinese or Japanese calligraphers are doing at a global scale, I realize how much more we need to do in terms of Islamic calligraphy.

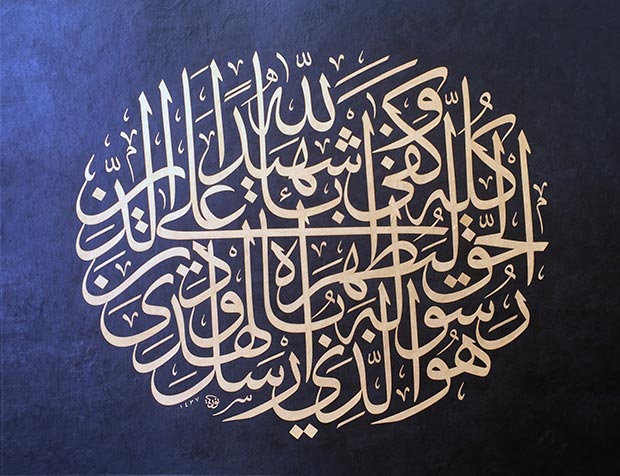

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip, Ahlul Beyt / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

Calligraphy by Nuria Garcia Masip, Ahlul Beyt / Courtesy of Nuria Garcia Masip

I think there is a lot of very valuable work being published, especially in Turkey and Iran, although it is mostly historical. I wish more would be written on the philosophy and theory of calligraphy, the way it was done in the past. In the English language, while there is a lot of academic work on the subject, I find there are not many books for a wider audience that address the practice of calligraphy in all its aspects. A lot more needs to be done.

I thank you too.

Comments

Add a comment