INTERVIEW Islamic Calligraphy Art By Mohamed Zakariya

Aug 21, 2017 Interview

This article is a part of the project 'Promotion of the Ottoman Cultural Heritage of Bosnia and Turkey' which is organized by Monolit, Association for Promoting Islamic Arts and supported by the Republic of Turkey (YTB - T.C. BAŞBAKANLIK Yurtdışı Türkler ve Akraba Topluluklar Başkanlığı / Prime Ministry, Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities).

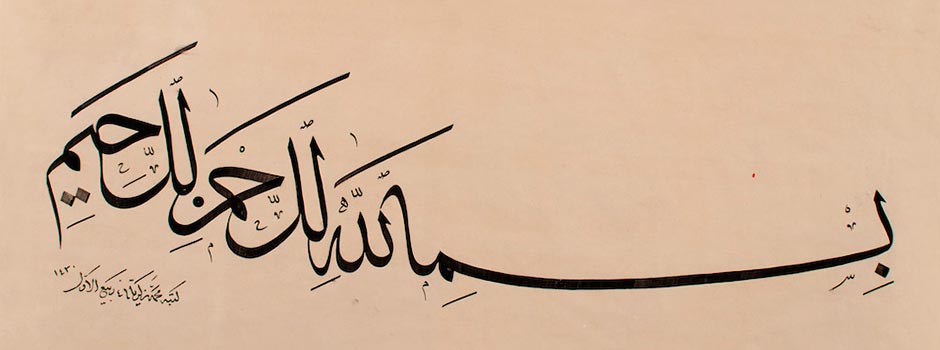

Photo above: Bismillah by Mohamed Zakariya

Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

I came from a small town in California and lived in a suburb of Los Angeles when I was growing up. The area was not very international at that time, and I was not aware of Islam. When I was about 18, I walked by a rug gallery (hali galerisi) owned by an Armenian. Through the window, I saw an item that drew me into the shop for a better look. It was on paper, black writing with a bit of gold and a bit of colour – a small Nesih-Sulus kitasi. “What is it?†I asked the rug dealer. “It’s Muslim art and you can’t afford it,†he replied.

But the kita had gotten my attention and captured my imagination. I began to learn Arabic and in 1961 travelled to Morocco, where I saw more calligraphy. I found Islam that year and never looked back. So although I don’t remember the rug dealer’s name, I still remember him and thank him silently for his kind gift to me – the gift of love for calligraphy.

At the time, having no experience, I saw the art as beautiful paper and materials and beautiful writing, full of energy. Later, I came to see it as a vehicle for deep meaning and communication – a candid snapshot, if you will, of art from times past and people long gone, a treasure of lost techniques, an alchemy of artistic method. But as I began to learn more Arabic, it was the meaning of the words that captivated me.

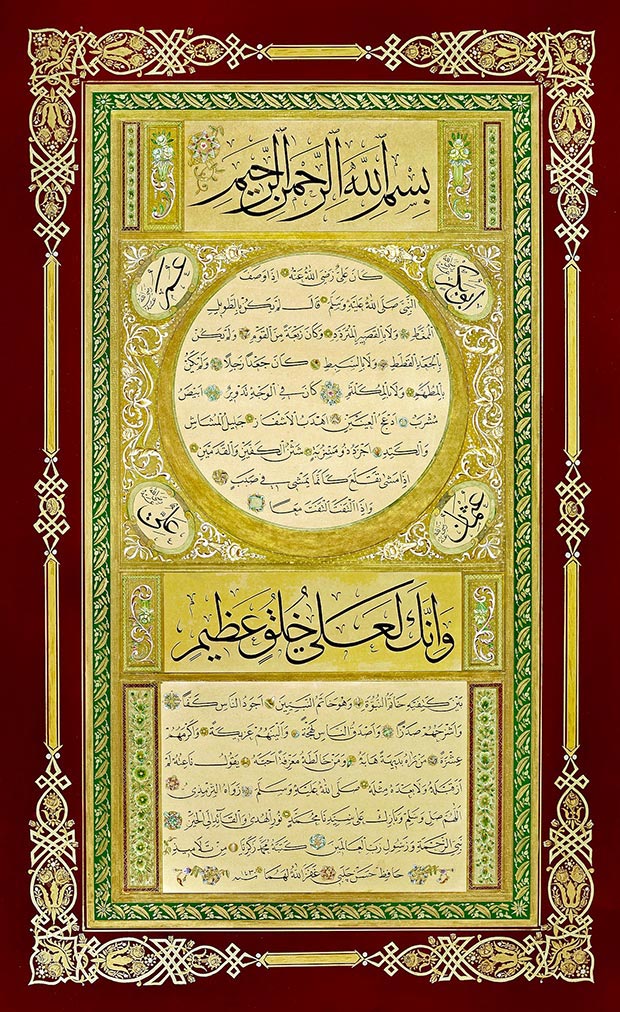

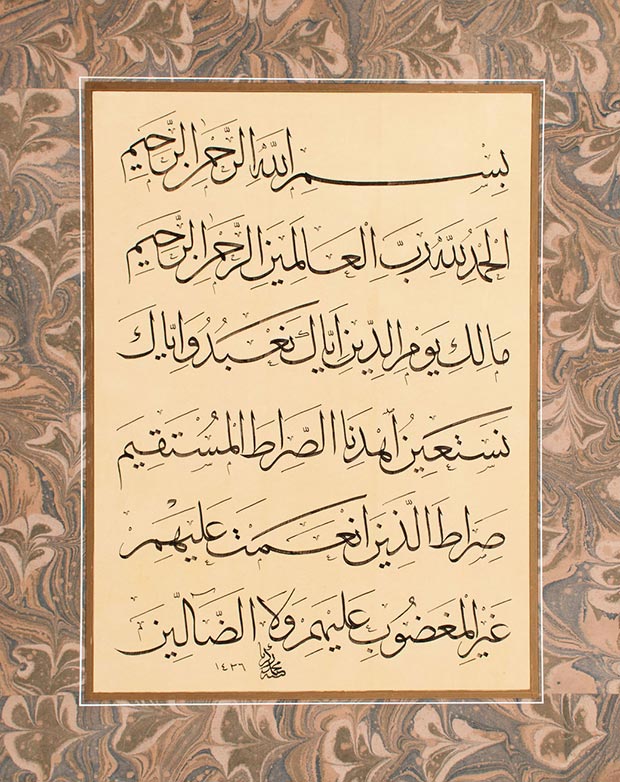

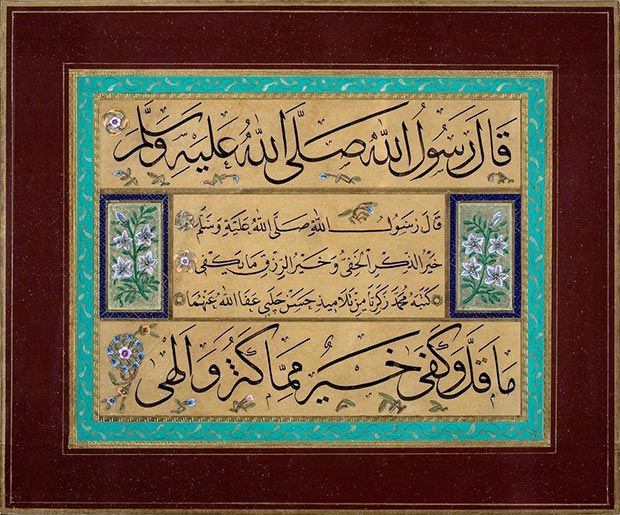

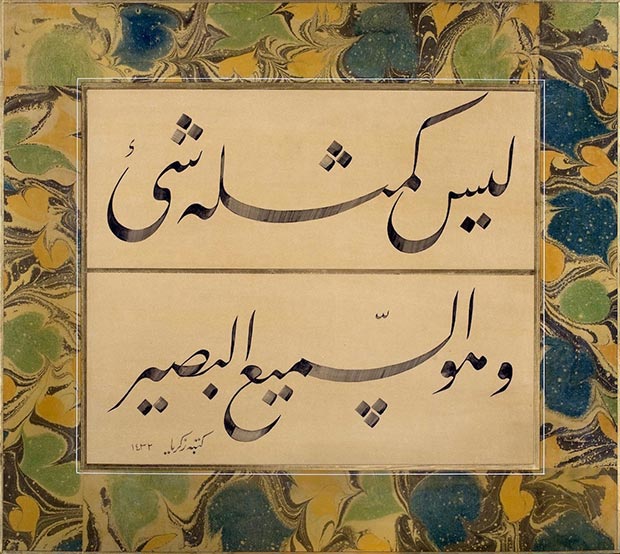

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

I never think of sacrifice. When I set out to be a calligrapher, I also became a machinist, woodworker, toolmaker, historian and comedian – skills that I still rely on to do special work. For a few years, I worked in small factories, for small salaries. In those days, if you wanted a job in Southern California, you simply looked for a sign saying “Help wanted†and you got the job and the training to perform it. My last job like that was in 1963, and when I left that work, I lost many friends and lost a small but regular income. To some degree, I also lost some of my American culture.

I travelled in Morocco, Europe, and, later, Turkey and the Gulf. I have never made much money, but I have made great friends and gained much knowledge. Yes, it was worth it.

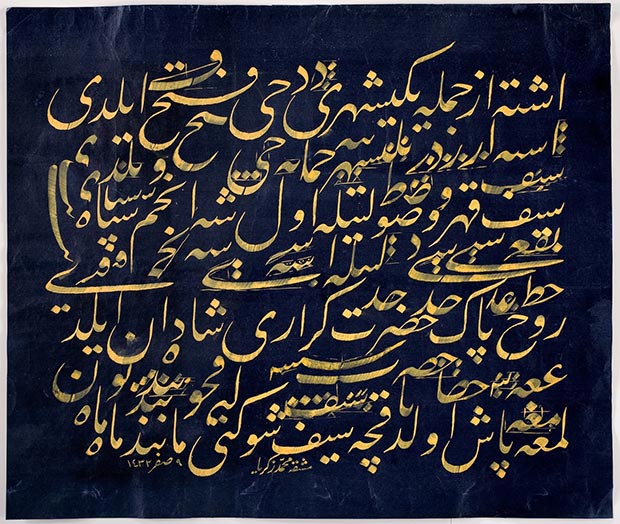

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

I would have to write a book about Islam in the U.S.A. in order to answer this question. The problems and issues here are different from those in other countries. First, to be any kind of artist or craftsman in America is generally an invitation to a life of poverty and disrespect. This is true for most artists, not just calligraphers. It is easier if you have a separate source of income. Our galleries do not generally welcome new artists or artists working outside the accepted trends. The Islamic arts are generally not wanted or appreciated.

On the other hand, among the advantages of living in the U.S.A. are the libraries and museums. They may not contain what calligraphers think they need, but magnificent surprises await every serious and curious person. We still have a few outstanding art supply stores and very good framing stores. You can also find tools and equipment that may be adapted to work for you, and if you are, like me, a toolmaker, you can make all the tools of calligraphy.

Americans such as my students can and do form clubs and societies for our art and hold regular meetings and discussions. In addition, we are sometimes invited to do lectures and demonstrations in museums, which are very popular.

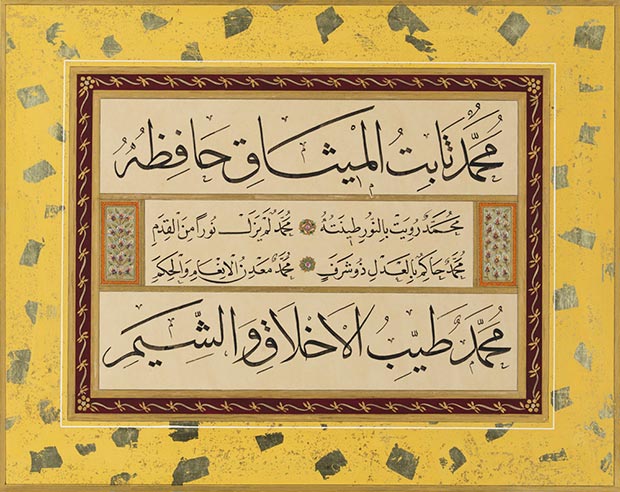

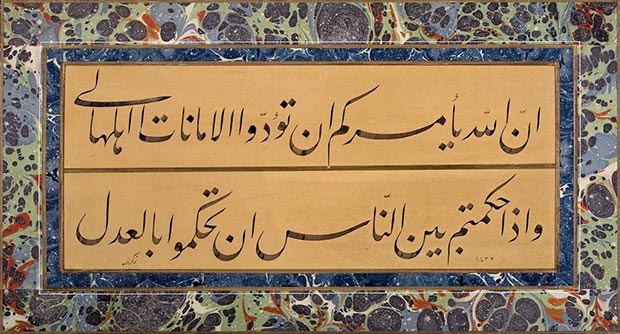

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

The typical American audience does not know what to expect when they attend a calligraphy event or exhibition. They are generally guided by stereotypical notions of calligraphy and calligraphers. It is our job to enlarge their horizons. Few audiences here have read about our art – indeed, little exists in English. So it is up to us to show, tell, and demonstrate – as we say, talim and tarif. We must put on a good show, one that is entertaining and informative while avoiding trouble spots. Occasionally hostile religious people can subvert a good show. The only time that has happened to me was years ago when a group of Salafi/Wahabi people attacked my lecture and caused much bad feeling and confusion. Religion itself can be a problem. There is little understanding among Muslims here about Islamic art and even about Islam itself.

People often ask about the use of computers in calligraphy. As for me, I do not use computers at all. I believe the art developed in certain ways and with certain materials in order to achieve certain goals. Our art is material, not virtual. Of course, as professional artists, we need to keep up with developments, some of which may be useful, but never in a crass way. I base my own work on earlier works, but my colours are unusual and my ebru is unique. My tezhip is simple, and not everyone likes it.

I think the old mesk system is the only successful way to teach and learn calligraphy. Other approached have been tried, but without much success. People can, of course, do as they want, but look around at the best calligraphers. I am sure you will find that they worked on their mesks. The one-on-one teaching is invaluable, and every time a hoca corrects a mesk for a student, everyone in the room – including the hoca – benefits. As a side issue, here in America, it is hard for people to understand why a hoca will not accept money or other payment for private lessons.

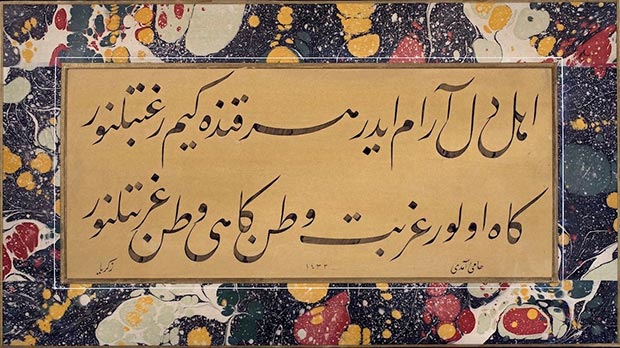

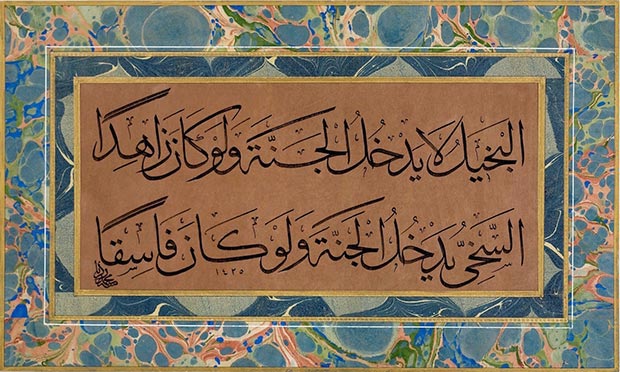

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

The calligraphy of Islam is new to Western culture – visually, aesthetically, intellectually, and from the standpoint of deep meanings. A calligrapher should know the languages required to search out new texts. When you simply copy the same old thing, people get bored with it. Personally, I like to do the Hilye. I’ve made many of them, from different sources, some better than others but none as good as I’d like it to be. The Hilye is a huge challenge. If you don’t honour the subject (aleyhisselam) through your art, you are just showing off. That is why we must plan our work out so carefully.

I believe in simplicity. If something does not need to be there, don’t put it there. I just finished a large, special Hilye – not the calligraphy, which was by someone else, but the yapistirma and tezhip. For colour, I used only tones of brown and green with a very small touch of red. The effect was interesting. I am really too old to do such work, which must be done standing because of the large size of the piece. I plan to continue with small works. One cannot claim that calligraphy has an important status in today’s world. Some people may say it does, but what is the better lesson is that the person who does the calligraphy is what makes it important. We ordinary calligraphers have to accept our status – we are not Hasan Celebi, Mehmet Ozcay, Davut Bektas, Nuria Garcia Masip.

But the purpose is not to make ourselves famous – it is to make our subjects famous. We have this duty. In some Muslim cultures, good calligraphy is not widely known, and exhibitions and contests can elevate people’s understanding. (In some exhibitions, the sponsors require works that are too big. What about smaller pieces?) In addition, the books by Ugur Derman should be widely translated so people will learn about these artists. Radio interviews, television discussions can also help bring up public awareness.

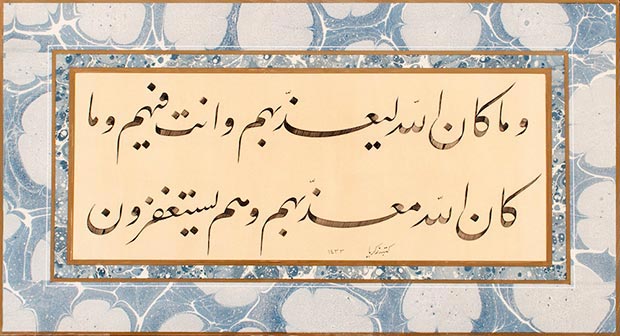

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Islamic calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya / Courtesy of the artist

Academic studies are useful. Although they are generally impractical, such studies are indispensable. The writers try to find new ways to describe a calligraphic work; our old vocabulary no longer works. As a result, new forms of criticism are emerging out of academic and philosophical methodologies, and works can be discussed accurately and excitingly. This trend could lead to the publication of new magazines that would be more useful and those that failed because of poor writing and problematic design. Our art requires better. Writing that is clear, practical, accurate, amusing, and up to date has a better chance of enlightening readers. But then there is the issue of financing, where many well-meaning projects fall apart.

The Muslim world, including Europe and America, is full of good amateur calligraphers, as well as a few top-level hocas. We now have an admirably large population of woman calligraphers, which is somewhat new to the calligraphy cultures. For real success, however, we also need experts in the manufacture of paper and ink. People who want to learn calligraphy cannot find good art materials. Also important are tezhip artists, high-quality journalists, and effective critics who can guide people to an art they have not yet experienced. This combination will begin to build a calligraphy culture like the one that existed during the late Ottoman period, particularly in Istanbul. A successful calligraphy culture will encourage more people to participate, both as calligraphers and as connoisseurs, critics, and collectors.

Just 35 years ago, there was no specially printing of calligraphic works or manuscripts. Since then, a world-class printing industry has developed in Istanbul that is worthy of the attention of lovers of the calligraphic arts. I would like to see the same degree of attention given to the other aspects of a vibrant calligraphic culture that I have mentioned.

And on top of all this, why not, with Prof. Derman’s leadership, revive the old Medresetul-Hattatin as a museum and teaching institute? A modest proposal.

I thank you too.

Comments

Add a comment