NECMETTIN ERBAKAN UNIVERSITY'S SUMMER COURSE (JULY 21- AUGUST 15, 2015) Konya: An Open-Air Museum of Islamic Art and Architecture

Jun 08, 2015 FEATURE, Art History

While the city is most understandably famous as the city of the 13th-century poet and mystic Jalal al-Din Rumi, Konya also hosts countless treasures in the way of monuments and museums. In fact, because of the large number of mosques, madrasas, tombs, khaniqas and hammams, Konya is often described as an open-air museum. Below are two of the key site's course participants will visit and study.

Konya was the capital of the Anatolian Seljuk dynasty. On the artificial hill that formed its citadel, it once housed a palace and elaborate city walls of which almost nothing remains. Still standing, however, is the mosque built and extended or remodelled by several Seljuk sultans from 1155 to 1235 C.E., the last being Sultan Ala al-Din Keykubad I to whom it owes its name. Eclectic in style, its aesthetic power is due in large part to its location overlooking the city. Still today, the monument defines Konya's skyline.

View of Ala al-Din Mosque and the hill known as the Ala al-Din Tepesi which, still the city's heart and centre, is a popular place for summer picnics or having tea at the cafe also perched on its slope / Courtesy of Necmettin Erbakan University

View of Ala al-Din Mosque and the hill known as the Ala al-Din Tepesi which, still the city's heart and centre, is a popular place for summer picnics or having tea at the cafe also perched on its slope / Courtesy of Necmettin Erbakan University

Frontal view of Ala al-Din Mosque. In front of the mosque on the right, a concrete covering protects the remnants of the royal palace / Courtesy of Necmettin Erbakan University

Frontal view of Ala al-Din Mosque. In front of the mosque on the right, a concrete covering protects the remnants of the royal palace / Courtesy of Necmettin Erbakan University

The monumental courtyard wall bears two entrance portals whose two-tone marble decoration indicates a Syrian influence, an idea confirmed by the name of the architect Muhammad Ibn Khawlan al-Dimashqi inscribed on the building. The conical roof seen rising above the front wall is characteristic of Anatolian funerary architecture and tops one of the two mausoleums found in the courtyard. While one is unfinished, the other houses eight Seljuk sultans who have been laid to rest therein.

The ceramic mosaic mihrab, despite its late Ottoman marble addition, offers up a hint of both the mosque's and the adjacent palace's former glory. Its polychrome decoration in blue, turquoise, white and black allows us to imagine the once similarly tiled dome designed by tile maker Karim al-Din Erdim Shah. The ebony minbar is equally important: dated to 1155 CE, it constitutes the oldest signed and dated artefact of Anatolian Seljuk woodwork.

The mihrab forms a characteristic example of Anatolian architectural ceramic revetment with its perfectly harmonized stylized floral and geometric motifs and its thuluth and Kufic calligraphy / Courtesy of Necmettin Erbakan University

The mihrab forms a characteristic example of Anatolian architectural ceramic revetment with its perfectly harmonized stylized floral and geometric motifs and its thuluth and Kufic calligraphy / Courtesy of Necmettin Erbakan University

Apart from the Ala al-Din Mosque, the two best-known buildings in Konya are the Karatay Madrasa and the Ince Minare Madrasa both built during Rumi's lifetime. While the former now serves as the Ceramics Museum, the latter has become the Museum of Stone and Wood Carving. The Karatay Madrasa sits at the foot of the Ala al-Din Tepesi, its portal's bichrome marble decoration or ablaq resembling that of the Ala al-Din Mosque. While the portal displays a well-thought-out display of geometric and calligraphic designs, the madrasa's true magnificence is to be found inside.

-in-Konya.jpg) The Karatay Madrasa (1251) / Photo by Valerie Behiery

The Karatay Madrasa (1251) / Photo by Valerie Behiery

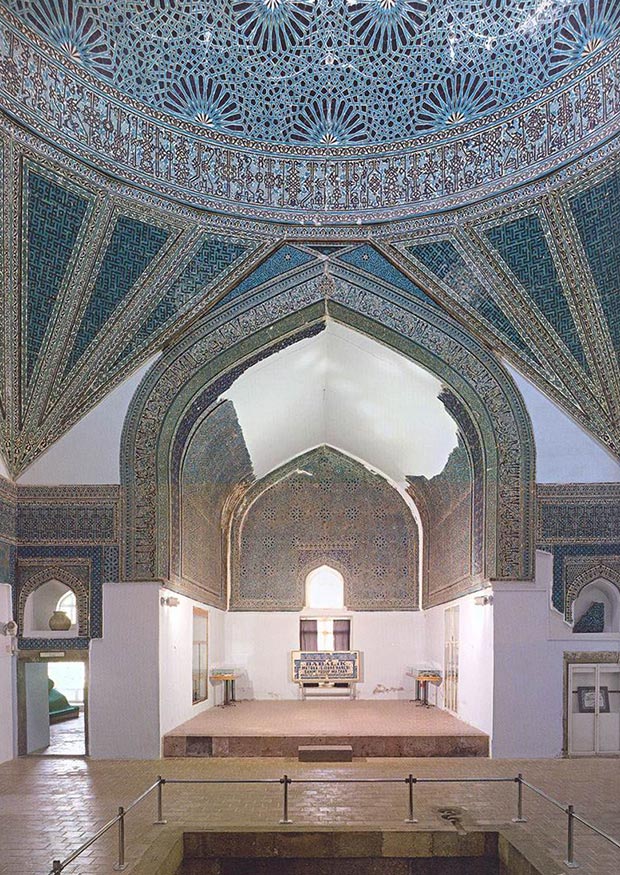

Interior of Karatay Madrasa. View of iwan and the space that would have once served as the main classroom / Courtesy of Necmettin Erbakan University

Interior of Karatay Madrasa. View of iwan and the space that would have once served as the main classroom / Courtesy of Necmettin Erbakan University

The building commissioned by Jalal al-Din Karatay, vizier to the Seljuk Sultan al-Din Kaykavus II presents an innovative transformation of the open courtyard design so prominent in Islamic architecture. Its single-iwan plan consists of rooms 'classrooms and student cells' arranged around a central domed rather than open-air space rather than the courtyard. The dome bears a large oculus that would have provided light and air; below it is situated a square pool.

The dome is entirely covered in blue, black and white tilework bearing a complex radiating star tessellating motif. Upon seeing it, it is impossible not to think of the night sky filled with glittering stars. That the designer wished to evoke the canopy of Heaven and, more particularly, its maker is further confirmed by the presence of Quranic verses, in particular the Throne Verse, in interlaced Kufic at the base of the dome. Also of interest here is the use of Turkish triangle pendentives bearing the names of the Prophet Muhammad, his four successors and five major prophets, including Isa or Jesus, in square Kufic.

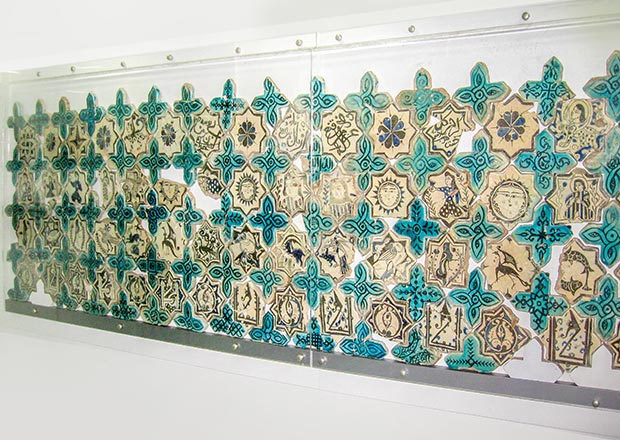

The building functioned as a madrasa until the early 20th century. In 1955, it became a ceramic museum undoubtedly due to the artistry and scale of its ceramic decoration. Its collection was formidably enhanced by the precious ceramic finds made by Prof. Dr. Ruchan of Ankara University at the Seljuk Kubadabad Palace situated approximately 100 km west of Konya, on the shore of Lake Beysehir.

The architectural ceramics of Kubadabad Palace consist mostly of the interlocking cross and star-shaped tiles: the former are turquoise with simple black abstract underglaze designs while the latter carries a host of imaginative calligraphic, figurative and zoomorphic designs on a white ground.

The ceramic ensemble on display at the Karatay Museum testifies to the craftsmen's mastery of a wide range of themes and overall creativity / Courtesy of Necmettin Erbakan University

The ceramic ensemble on display at the Karatay Museum testifies to the craftsmen's mastery of a wide range of themes and overall creativity / Courtesy of Necmettin Erbakan University

Luster tile on view in the Karatay Museum. In addition to real animals such as foxes, horses, rabbits, dogs and birds, composite or supernatural creatures also abound in Anatolian medieval ceramics raising the question of iconographic meaning / Courtesy of Necmettin Erbakan University

Luster tile on view in the Karatay Museum. In addition to real animals such as foxes, horses, rabbits, dogs and birds, composite or supernatural creatures also abound in Anatolian medieval ceramics raising the question of iconographic meaning / Courtesy of Necmettin Erbakan University

Comments

Add a comment