Passion for Perfection - Islamic art from the Khalili Collections

Dec 09, 2010 Art Collection

These are works of great historical and artistic value, illustrating the refinement and grandeur of Islamic art and bearing witness to a quest for perfect craftsmanship. Passion for Perfection shows that Islamic art is a masterly expression, not of a single national culture or civilization, but of the many peoples joined by Islam for more than 1,400 years. At the same time, the exhibition demonstrates the passion and expertise of Professor Khalili, who has assembled an unrivaled private collection of exceptionally fine Islamic art objects. The exhibition designer is Siebe Tettero, particularly known for his work for the Van Gogh Museum, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and the fashion house of Viktor & Rolf.

The central theme of Passion for Perfection is the beauty and exquisite workmanship of Islamic art. The Islamic world is highly diverse, geographically and culturally, and more than thirteen centuries of Islamic artistry are represented in the Khalili Collections. It includes masterpieces from all over the Islamic world: from China and India to Iran and Iraq, from Egypt and Tunisia to Turkey and Spain.

The term ‘Islamic’ does not imply that all these works of art were made specifically for religious purposes; it is their artistic language that is rooted in Islamic philosophy, often reflecting local culture and traditions. Besides calligraphic decoration and geometric patterns, arabesques and elegant scrollwork, there is also a strong emphasis on representations of humans and animals, the latter tolerated only in secular contexts. Many such representations are found in miniature paintings and in virtually all of the branches of the decorative arts.

The exhibition will be divided into themes such as Captivating Calligraphy, with magnificent illuminated Qur’ans and rare manuscripts dating from the 10th to the 19th century, Shining Showpieces, with ingeniously fabricated jewelery adorned with precious stones, as well as colourful enamels that belonged to India’s Mughal rulers, and Delicately Drawn, with the finest miniatures from Iran and India. One highlight is the Jami‘ al-Tawarikh, the first survey of Muslim history, written from the perspective of the Mongol conquerors by Rashid al-Din in 1314’1315.

This is the first time that such a large selection from the Khalili Collections is to be displayed in the Netherlands. The exhibition was previously shown in Sydney, Abu Dhabi, and Paris.

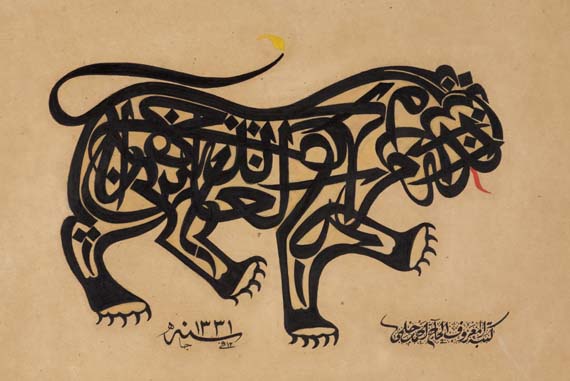

Calligraphic composition in the form of a lion

Signed by the calligrapher Ahmed Hilmî

Ottoman Turkey, dated 12 Jumada I 1331 (19 April 1913)

Ink and watercolour on paper

CAL 242

The lion is composed of invocations to ‘Ali, one of whose common titles is ‘The Lion of God’.

Hemispherical bowl

Egypt, 10th century

Deep blue glass over a colourless matrix, blown in an open mould, cameo cut, lathe turned and relief cut

GLS 550

Cameo-cut glass is a technique probably intending to imitate carved rock crystals or other hardstones of Iranian or Fatimid Egyptian manufacture. Such vessels must have been commissioned and are unlikely to have been sold on the open market, the skill and intricate workmanship demanded making them as expensive as the hardstones themselves.

Pair of earrings

Syria or Egypt, 10th or 11th century

Gold wire and sheet, with filigree and granulation

JLY 2149

On the outer faces of the box-constructed earrings is a small filigree bird.

Dagger

India, Rajasthan or the Deccan, 18th century

Blade: watered steel, with armour-piercing tip; hilt: pale green jade inlaid and encrusted with gold, rubies and foiled emeralds in gold kundan settings

MTW 1135

Weapons with hilts of fragile materials such as jade were for formal wear rather than use. The surface of this hilt is decorated with fine gold scrolling arabesque with ruby- and emerald-set florets; the gold is lightly chased, imitating foliage, a technique seldom observed in India. The kundan technique uses pure gold that can be pressed into hollowed spaces without heating. This is essential, since gold inlays cannot be beaten into the fragile jade.

Thumb-ring

Mughal India, 17th or 18th century

Greenish-grey nephrite jade, set with rubies, diamond and emerald in gold kundan

JLY 1121

Pendant in the form of an eagle

Mughal India, 18th century

Gold, cast and chased, set with foiled diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires in gold kundan

JLY 2151

The heraldic stance of this pendant was popular in European jewellery of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and these jewels may reflect a tradition established by Italian craftsmen working at the Mughal court in the 17th century. This may also explain the use of sapphires, which native Mughal jewellers generally tended to eschew.

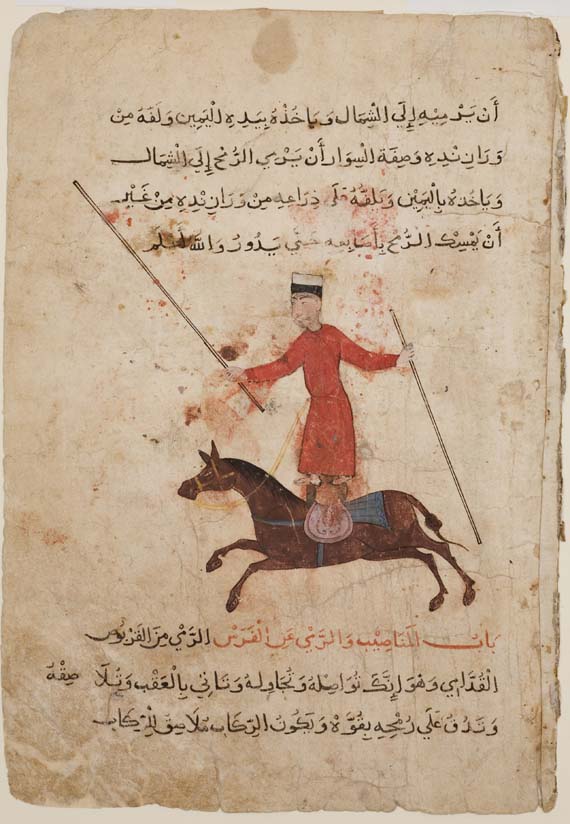

Two folios from a furusiyyah manuscript

Mamluk Egypt, 15th century

Ink and opaque watercolour on paper, naskh script

MSS 662.1, MSS 662.2

The early Abbasid caliphs gave prime importance to horsemanship (furusiyyah) as an embodiment of knightly culture, and the mass recruitment of Turks into their armies brought a need for manuals of cavalry training. The two folios show young Mamluks in armour on horseback, standing in the saddle and juggling with staves or lances.

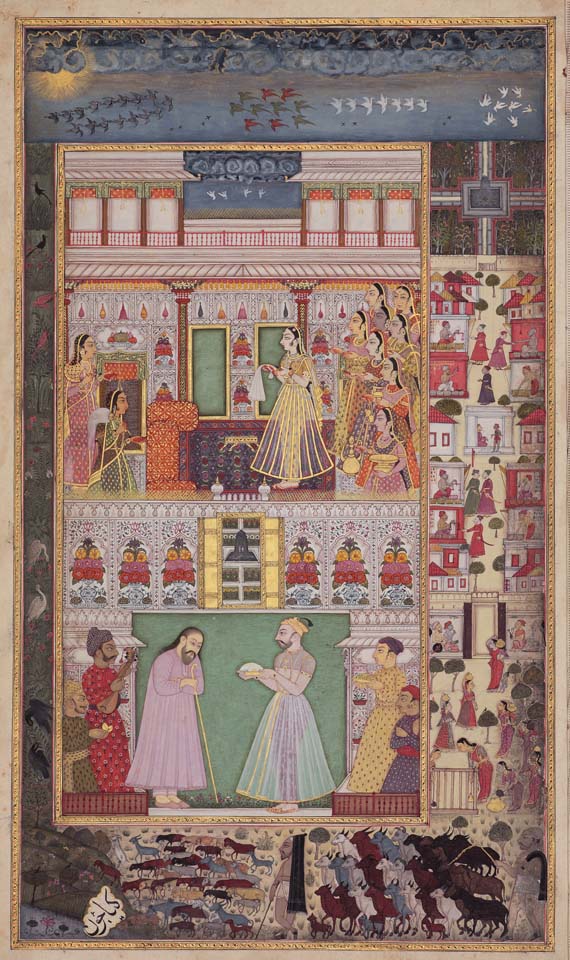

Double page from the Gulshan-i ‘Ishq (the rose garden of love) by the Sufi poet Nusrati

India, Hyderabad (the Deccan), circa 1710

Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper

MSS 640.1, MSS 640.2

The Gulshan-i ‘Ishq is an allegorical romance relating the progress of King Bikram towards enlightenment and the birth of a child to his hitherto barren queen. The paintings are of two types: those illustrating the narrative, which are bolder and larger in size, such as the despondent queen in her private apartments; and marginal vignettes, which are virtual microcosms of daily life at court, in the city and in the countryside.

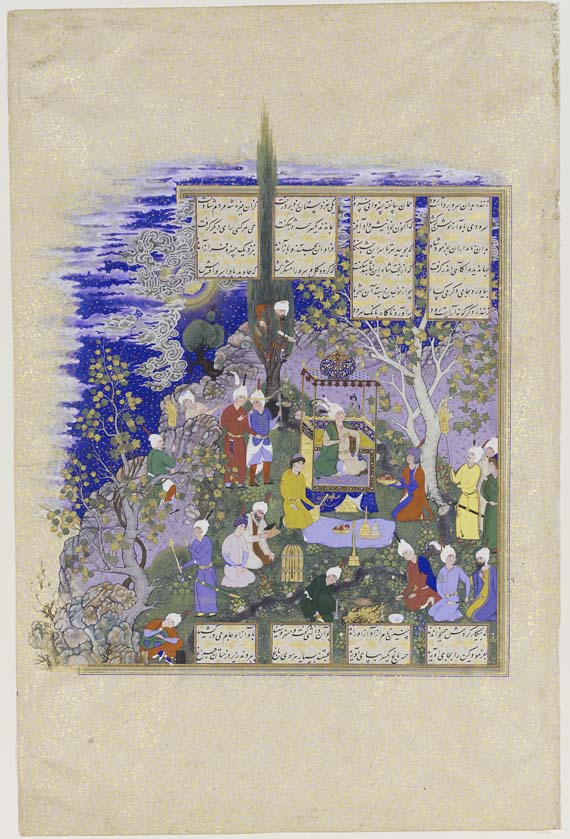

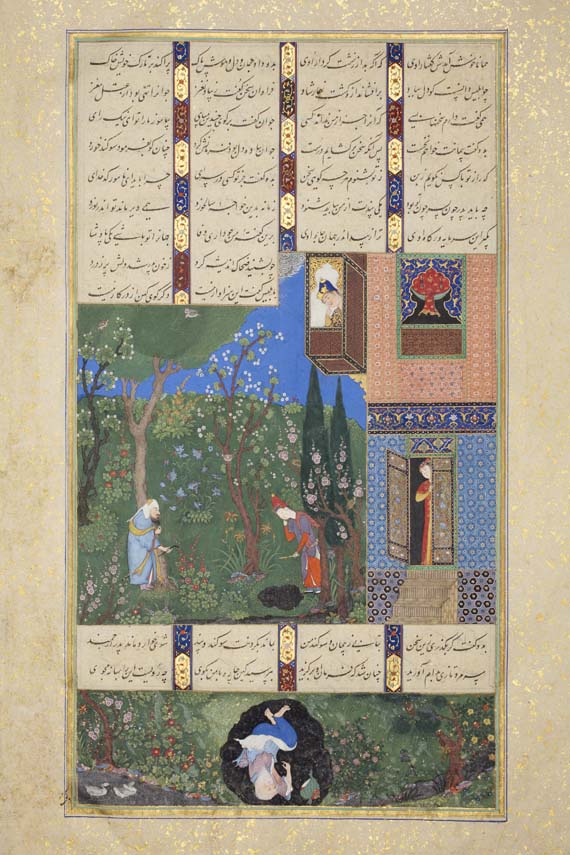

The musician, Barbad, conceals himself in a cypress tree and enchants King Khusraw Parviz with his playing

From the ‘Houghton’ Shahnamah

Attributed to the painter Mirza ‘Ali

Iran, Tabriz, circa 1535

Ink, gold and opaque watercolour on paper

MSS 1030, folio 731a

The ‘Houghton’ Shahnamah (so called after the collector who broke it up in New York in the 1970s), was copied for the Safavid Shah Tahmasp, and is considered the finest illustrated Persian manuscript ever made. Of large format, it is written in calligraphic nasta‘liq, on fine paper, brilliantly illuminated and gold-sprinkled and was furnished with 258 illustrations. Its production, even with a large team of fine painters and other craftsmen, certainly took more than a decade and may even have continued into the 1540s, involving a second generation of painters. The format is independently conceived for each painting and must have involved constant consultation between scribes, painters and marginators. General features, however, include a new approach to the technique of painting in opaque watercolour: treating the paint as if it were colour wash; a new subtlety of shading and modelling in pastel tones; the building up of tones and the enhancement of colour by gilding and silvering; and the use of mother-of-pearl and powdered talc to give sparkle. The details of the costumes, arms and armour, horse trappings and furniture remain an unsurpassed document of the rich material culture of the age.

Mirdas, king of Arabia Deserta, lies with his back broken at the bottom of the pit dug for him by his son, Zahhak, at the instigation of the devil, Iblis

From the ‘Houghton’ Shahnamah (book of kings)

Perhaps by the painter Sultan Muhammad

Iran, Tabriz, 1520s

Ink, gold and opaque watercolour on paper

MSS 1030, folio 25b

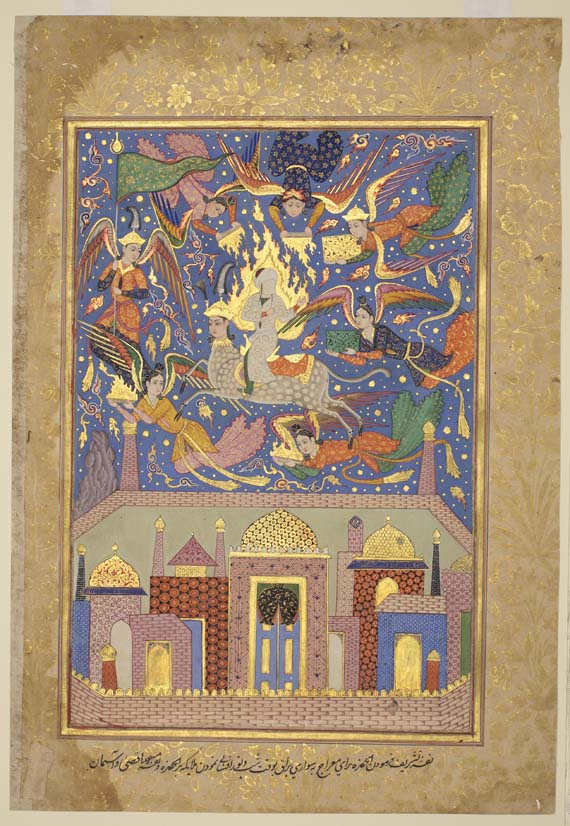

Falnamah (Book of Divination)

India, the Deccan, probably Golconda, circa 1610–30

MSS 979

This painting is from a Falnamah, a book of divination or omens. The book consists of 36 paintings, opposite each of which is a text that predicts the outcome of the scene depicted in terms of delivering good, bad or variable fortune: if the prediction is unfavourable, the text recommends how to forestall it, delay a decision or avoid the predicted outcome with a charitable donation. The varied subjects include episodes from al-Kisa’i’s Qisas al-Anbiya’ (tales of the prophets), an anthology of Christian, Jewish and Muslim legends; episodes from the life of the Prophet Muhammad; episodes from the poet and philosopher Nizami’s Khamsah; and depictions of miracle-working Sufis.

Tall flask

Probably Bohemia, later 19th century

heavy ruby glass, blown and tooled, with enamelled decoration and gilding

GLS 609

This is a copy of a 14th-century enamelled Mamluk flask acquired by Baron Gustave de Rothschild in Paris in 1864 and illustrated in Eugène-Victor Collinot and Adalbert de Beaumont’s Ornements de la Perse, a 19th-century encyclopaedia of oriental decorative arts. Ruby glass was a well-known 19th-century Bohemian speciality.

Decorative attachment for an astronomical instrument

Northern Iraq, Mosul, 13th century

Brass, cast and engraved

MTW 825

This suspension bracket may have held a large, freestanding quadrant, sextant or astrolabe in an astronomical observatory. It bears the engraved signature of its maker, Shakir ibn Ahmad, and is decorated with openwork arabesques, the curves of which are strongly reminiscent of the gaping jaws of dragons.

One of four wooden roundels

Ottoman, 19th century

Wood, carved in champlevé, with gilt thulth script on a ground painted dark blue

MXD 265a–d

Ottoman mosque architecture was dominated by central domes, the pendentives of which often bore roundels, of painted wood or tilework, with the names of God, Muhammad, Abu Bakr, ‘Uthman, ‘Umar and ‘Ali, and sometimes the names of Hasan and Husayn too, and appropriate prayers for each. The four roundels on show are inscribed with the names of Allah (illustrated), Abu Bakr, ‘Uthman and Hasan.

Turban crown

Nepal, 19th century

Diamonds, natural pearls, foiled rubies (genuine and synthetic) and emeralds, green glass; gold, enamelled gold and silver mounts, gold thread and silver strips; wood or papier-mâché covered with maroon velvet

JLY 1071

The combination of turban and crown symbolised the bond between religious and secular leadership in the Muslim world, especially on the Indian sub-continent, where the Mughal emperors and their vassals boasted of a long tradition of jewelled turbans.

Panoramic view of Mecca

circa 1845

painted by Muhammad ‘Abdallah, the Delhi cartographer

ink and opaque watercolour on paper,

62.8 x 88 cm

MSS 1077

This view of Mecca is remarkable for its comprehensiveness and accuracy and, in the manner of contemporary topographers, brilliantly combines a plan of the city with a bird’s-eye view from about 60 degrees. Muhummad ‘Abdallah, whose grandfather, Mazar ‘Ali Khan was court painter to the Mughal ruler, Bahadur Shah II, was commissioned by the Sharif of Mecca to depict the sacred monuments of his realm in the second quarter of the 19th century. It is the earliest known accurate eyewitness record of the city.

De Nieuwe Kerk Amsterdam Dam Square, Amsterdam

T: 020 - 626 81 68

.(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

http://www.nieuwekerk.nl

Comments

Nov 30, 2011 - 14:38:46

nice rare collection…but i can not find the old script carving on glass like calligraphy on blue cobalt glass???is it that rare? looking to buy ....

Feb 16, 2011 - 17:10:02

What a wonderful idea! Love the magazine and will subsrcibe.

Good luck!

Jan 06, 2011 - 17:11:08

I was lucky to visit the Khalili collection twice: in Sydney at the Art Gallery of NSW and in Paris at the Institut du Monde Arabe:

a pure marvel.

Dec 22, 2010 - 9:58:45

hello, I need some information about (calligraphy : the lion of God ) WHAT IS THE MEANING THAT ARABIC FOUNT ON BODY OF THAT LION ? THANKS…

Add a comment