AN INTERVIEW WITH IRANIAN ARTIST ANAHITA NOROUZI Screening Place, Time and the Body

Oct 18, 2013 Interview

Anahita Norouzi is an Iranian artist who lives between Iran and Canada. Having earned a Bachelors degree in graphic design from Tehran’s Soureh University, she moved to Montreal and completed her MFA at Concordia University. Her photo-based work and videos have been exhibited in several group shows in both Iran and Canada. This year, Norouzi was one of seven finalists for the prestigious Magic of Persia Contemporary Art Prize whose Finalists’ Exhibition is on view at London’s Royal College of Art from October 15 to October 19.

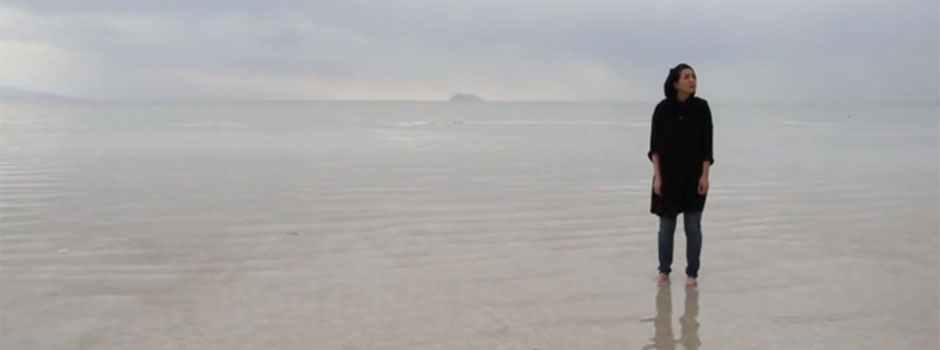

Anahita Norouzi / 'Sequence 01' / Courtesy of the Artist

I guess reading ‘Camera Lucida’ and ‘The Death of the Author’ by Roland Barthes when I was doing my undergrad changed my perception of time, what is the ‘real’, and what is the ‘live’. I became fascinated by the notion of time and all possible ways to use it as a component of a piece.

My style in photography is in complicity between the two media. Both employ imagination to recreate the reality of lived experiences. It’s only ‘time’ that is treated differently in my moving images and still images. But in general, as an interdisciplinary artist, I’m curious about working with a broad range of materials and media. For me, the process of art making as an experience is as important as the piece itself. I’m very interested in the interrelation of different materials, and how, ontologically and art-historically, one medium affects another. I chose a particular medium whose effects would help in the communication of my piece.

To answer this question, first I'll refer to a quote by Badiou: "Art is the production of an infinite subjective series through the finite means of a material subtraction." I don’t want to reduce the possible "infinite subjectivities" into a particular narrative or story whose meanings might be opaque to others; on the contrary, I intend to guide the visitor towards infinite subjectivity. In fact, one of the reasons that I present the videos in the loop mode is to situate the visitor in a continuous accelerating circulation so that at some point a rupture may occur and then the visitor can be guided towards an unexpected contingence.

Getting back to your question, I agree that there are a number of peculiarities in my videos, which are deliberately considered: the presence of my body, the locations, and the specific portion of time, in a specific historical context that the videos were capturing. But I’m wishing that in the eyes of a visitor, these peculiarities could be read in the multiplicity of the infinite ways.

From your question "a vision onto nowhere or onto something that will always be" I can extract two words: change and destination.

My act of moving —the voyage— creates a structure in which time and space coexist. I’m so interested in the existing duality between these two: sometimes they complete each other, and sometimes they contrast one another. I think here is where the notion of time starts having meaning in my work.

There are many in your question that I can refer to: minimalism, phenomenology, repetition, and cinema. I totally agree with these.

The issues related to body and gender have always been a concern in the performance art. And indeed, Abramovic, Chris Burden, Vito Acconci… they are very characteristic in the history of performance art. But I don't want to be limited to them. I think the answer to your question is yes and no. It’s yes, because here we are talking about performance art in which the artist’s body is often used as the main material. And It’s no, because I'm referring to none of these artists specifically.

Again, talking about ‘infinite subjectivity,’ I just mentioned phenomenology because it refers to the multiplicity of meanings of a same experience that different people could have… the experience of self, others, or time. My presence as a material in the work induces, again, the ‘infinite subjectivity.’

And the Seventh art? Sure, why not! I started creating images through photography, very much under the influence of Eastern cinemas and more precisely the aesthetics and structure of Iranian cinema: still frames, long shots, and minimal movements.

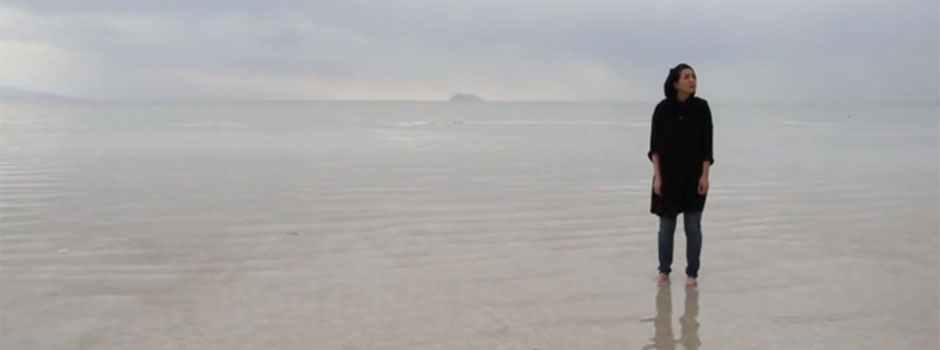

Anahita Norouz / 'Emigrating to Where I Dwells' / Courtesy of the Artist

As I write in the text I exhibit with the piece, the rings of history in a tree's trunk symbolically carry the very material of history. If we have to read this in the symbolic way, I'm planting new possibilities for making a new history, although limited. It’s interesting to think: I’m using my body as means of creating something that lasts longer than ‘I,’ a monument, immune from the secular experiences of time. My act is historical so is the video.

I think the trees symbolically are not as pregnant as Damavand. Damavand is the origin of myths, legends, and tales. It’s a part of our lullabies. It stands for resistance, divinity, and pride, and has always been associated with Iranian national and cultural identity. Damavand is sole, it’s a familiar image for all Iranians, regardless their political interests.

Anahita Norouz / ‘One Hundred Cypresses’ / Courtesy of the Artist

For Iranians the notion of ‘historical progress’ is a brutal, unrelenting illusion. The Iranians experience of time and history has always been jostled with its very erosional and destructive nature; or better to say, it’s always been juxtaposed of the idea of destruction on the one hand and preservation of what has been destructed on the other – by preservation here, I mean preserving the memory of what has been destroyed.

Iranians’ unconscious perception of history is the history of ruins – a recurrence of a "catastrophe that keeps piling ruin upon ruin."

I agree that the visual aspect of my works is accompanied by a poetic turn, which is the very characteristic of visual identity of Iranian national cinema. There’s a kind of intertextuality between image-making traditions and literature in Iranian cinematography. In fact, in such cinemas like Kitarostami, Farmanara, or Makhmalbaf’s early films, images represent a cinematic equivalent of Iranian poetry.

My images are primarily the illustration of uncomfortable situations that I confront in my life, a way to recapture my personal history in order to reflect on my living experiences.

I had to leave Tehran in the winter 2010. It was entirely my choice to leave; yet, it was the most dramatic experience of my life. It pushed me to go through a very rapid phase of absolute and drastic transformations. It put a question mark on all aspects of my individuality through which I could recognize myself. It changed my definition of certain words such as home, change, sameness, and time.

This displacement radically dislocated my position towards home and put me in a contradictory situation, like living in duality, the experience of ‘insideness’ and ‘ousideness.’ But I must admit that this experience of absence, as an artist, was a privilege for me. "Things too close to self to be touched, smelled, and tasted cannot be seen clearly." It created a window so that I could look at my homeland differently and be able to contemplate it in the form of art.

Your art hinges on self-presentation and yet, neither auto-fictive nor documentary, it is equally never self indulgent. The focus on the body and performance, the monumentality of space and place, and your seamless integration into the landscapes somehow open up a space of complete freedom for the spectator. How do you read the use of your person in your work and anticipate its’ reception?

In ‘We all knew that here is the place of ordinary objects,’ images embody the places that I have experienced and ‘I,’ and the interconnections between us. Place is a type of object in my work as well as ‘I.’ My presence carries the same weight as my background. We both mirror the era that I live in. I’m talking about the era of decay when everything is uncertain, and I’m not sure —while standing beside Lake Urmia— the current visual field in front of me, which is a part of my childhood photographs, would be the same, or even exist, the next time that I’d be there.

All these places are the tangible result of my fathers’ father experiences. They are the reincarnation of the historical memory of a nation onto an object. This peculiarity, attached to a lifeless object, transforms it into a monument. Of course for a person who has experienced it: for you as a Canadian, for example, Persepolis lacks the weight of reality; it’s an abstract concept. "You look at it, you can’t recall it, no familiar detail interrupts your interpretations, you’re interested in it, but you don’t love it." For you it’s not punctum, it’s not a monument. But for those who have experienced it, it has a time-related quality which I can’t really name.

Anahita Norouz / 'We all knew that here is the place of ordinary objects' / Courtesy of the Artist

Working as much possible and running shows as many as possible! I guess for the moment, I have taken what I needed from school. My freedom now gives me enough time to go back to my studio and my project notebook.

My pleasure. It was great talking to you.

Comments

Add a comment