AN INTERVIEW WITH FRANCO-ALGERIAN ARTIST SAMTA BENYAHIA ‘Silent Synchrony’

Jan 28, 2014 Interview

Samta Benyahia is a Franco-Algerian artist who lives and works in France. A graduate of the French national school of decorative arts (ENSAD) in Paris, she taught at the national art school in Algiers from 1980 to 1988. However, Samta returned to Paris in 1988 to pursue graduate work in the arts and has made the city her main home ever since. She has exhibited internationally including at the Venice Biennale, the Bamako Biennale, the SantralIstanbul, and the Fowler Museum of Art in California and her work figures in many public and private collections both in France and the Maghreb. The artist draws upon her Amazigh and Arab heritage to make—often site-specific—contemporary art. If Samta Benyahia uses a variety of materials and techniques from sequins to photography, the reference to women and the hope of global understanding have remained constant themes in her decades-long career.

Samta Benyahia, photo by Jean-Christophe Sergère / Courtesy of the Artist

Samta Benyahia, photo by Jean-Christophe Sergère / Courtesy of the Artist

The centerpiece at the Mamia Brétésché Gallery around which the exhibition revolves is a stained glass window, a blue rosette on glass measuring 90x90 cm. Entitled 'The Starry Polygon: Nedjma'—a title borrowed from the great Algerian writer Kateb Yacine—, this stained glass was produced at the same time as those forming part of 'Constantine of my Childhood' acquired by the American Art in Embassies Program in 2003. It is exhibited away from the wall by about 6 or 8 cm in order to highlight the effect of shadow and light and to play on transparency. The piece is the guiding thread of the exhibition designed for the gallery space that is relatively small, but nonetheless very beautiful.

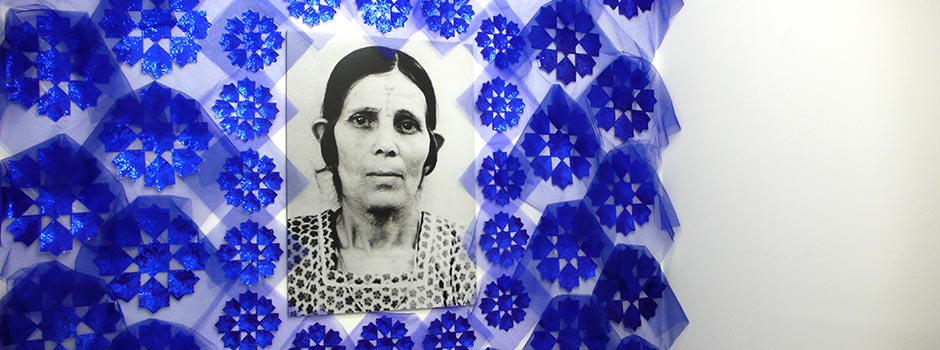

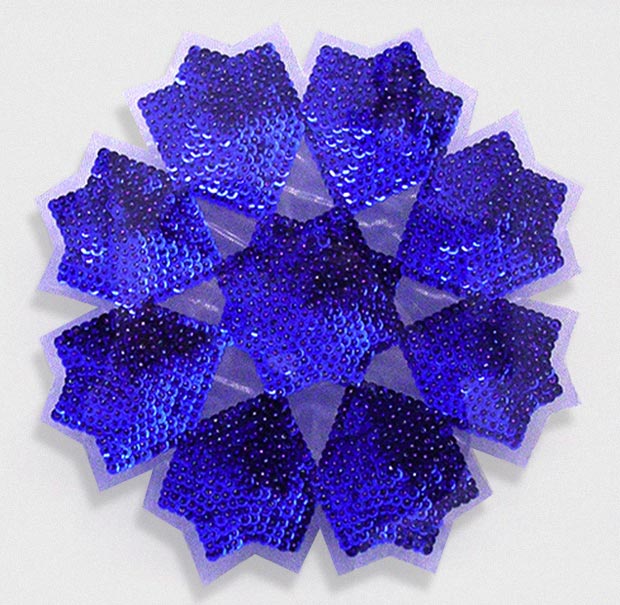

Around the stained glass and on the main wall of the gallery are presented in a purposefully saturated fashion are photos, drawings, silkscreen prints as well as rosettes embroidered in blue sequins and seed beads on tulle similar to those displayed in two previous exhibits: 'La vie en paillettes' at the Clermont Ferrand Museum in 2003 and 'A la lumière des matins…Albert Camus' at the Martine et Thibault de la Châtre Gallery in 2008. On the other walls of the gallery are exhibited photos of different mise-en-scènes of fabric that I had printed with the blue rosette motif. These are related to my 2013 installation called effectively 'Le drap' ('The Sheet'). What I’m trying to emphasize here is that this recurrence, adaptation and continuity of certain themes and elements are intrinsic to my work and approach.

The public will also find the photographic poliptych focusing on lace and textiles. It’s a piece that tells the story of the young women from my mother’s generation for whom the preparation of the bridal trousseau was a way for them to come together around a joint project, build relationships and express themselves. It’s also a story linked to my childhood and the still vivid memory I have of the numerous spools of golden thread, balls of colored wool and piles of lace and cloth of all sorts that surrounded me.

Samta_Benyahia / 'Fatima', tulle embroidered with sequins and seed beads, diam 45 cm, 2003-2013 / Courtesy of the Artist

Samta_Benyahia / 'Fatima', tulle embroidered with sequins and seed beads, diam 45 cm, 2003-2013 / Courtesy of the Artist

Samta_Benyahia / Installation of 'Fatimas', Gallery Martine et Thibault de la Châtre, Paris, 2008 / Courtesy of the Artist

Samta_Benyahia / Installation of 'Fatimas', Gallery Martine et Thibault de la Châtre, Paris, 2008 / Courtesy of the Artist

This visual abundance created by the transposition of images, colours, techniques and light and shadow also brings me back to my childhood and the countless hours I spent observing the magical world created through the eye of a kaleidoscope, an object that constitutes an extraordinary analogy for my artistic approach, regardless of the different mediums I’ve used throughout my career: painting, engraving, sculpture, printing, photography, embroidery, performance, video and sound works... In fact, in all there is a reflection to infinity and in color for which an architectural space becomes—for the time of the exhibition—a theatre where all these expressions or mediums intersect, overlap, are combined and become a way to engage in dialogue, and communicate with the visitor who, in turn, appropriates for him or herself the story and experience. This is what I strive for in my art.

Samta Benyahia / Left: 'Le Drap du Silence' (The Sheet of Silence) installation, Arabesque sur Seine, Centre Culturel Max Juclier, France, 2014. / Right: 'De Perles et de Paillettes' (From Beads to Sequins), Arabesque sur Seine, Centre Culturel Max Juclier, France, 2014 / Courtesy of the Artist

Samta Benyahia / Left: 'Le Drap du Silence' (The Sheet of Silence) installation, Arabesque sur Seine, Centre Culturel Max Juclier, France, 2014. / Right: 'De Perles et de Paillettes' (From Beads to Sequins), Arabesque sur Seine, Centre Culturel Max Juclier, France, 2014 / Courtesy of the Artist

Samta Benyahia / 'Le drap' (The Sheet ), C-Print, various dimensions, 2013 / Courtesy of the Artist

Samta Benyahia / 'Le drap' (The Sheet ), C-Print, various dimensions, 2013 / Courtesy of the Artist

The importance of photography in my work does not date from today. It first appeared in the guise of the black and white portraits of women introduced into my installation in the early 1990s which was in a sense imposed on me by the force of the circumstances of a very difficult period in Algerian history. As an artist, I couldn't remain insensitive to the violence meted out against both women and men who were in the front line. It was at this time and in reaction to this tragic situation that I introduced the portrait of women—and especially that of my mother—into my work and which became the symbol of all women who resist obscurantism the world over. Over time, this portrait of my mother whose beauty and intensity of gaze challenge the spectator has become like a universal icon. More generally, I love photography; it is a lightweight art, perfect for the nomadic artist that I am.

This being said, I've always worked with the multiple. In the beginning, it was printmaking, and the element of repetition at the heart of my work derives from there and perhaps even from earlier work, paintings based on the repetition of Berber motifs and signs. After working with painting and engraving, I began using photography, photocopying, and screen-printing. The reproductive capacity of these technologies has served me in my installation work. For example, several interventions in architectural spaces were created using silkscreen on electrostatic film that covered surfaces ranging from a few dozen to a few hundred square meters. Or in an early 1994 piece, I multiplied the same portrait of my mother, photocopying it and gluing it to over 3 meters of canvas.

Samta Benyahia / Installation view of 'In the Light of Morning,…Albert Camus', Gallery Martine et Thibault de la Châtre, Paris, 2008 / Courtesy of the Artist

Samta Benyahia / Installation view of 'In the Light of Morning,…Albert Camus', Gallery Martine et Thibault de la Châtre, Paris, 2008 / Courtesy of the Artist

The reference to Amazigh woman is for me a vital symbol since the word Amazigh actually means a free man. Very modestly, by introducing the portrait of women in my work, I’m taking a position to say no to violence against women. I was going to say that, at the outset, the gender aspect of my work arose as a political stand against the Algerian civil war. But it was there even before, for example, in my work in the 1970s that focused on the signs and symbols of Amazigh traditional arts and that was undertaken under the direction of Marcel Fiorini, a French artist who invented new methods in printmaking in the second half of the 20th century and whose work is characterized by a great sense of freedom.

The reference to pre-modern artistic traditions in Algerian contemporary abstract painting has always inspired me. Working on the memory of the sign, I realized that the motifs related to the female arts transmitted by women through art, decor, cooking and music were part of this memory and so, of course, the traditions of pottery, tattooing, weaving, and mural painting of the Aurès and Kabylia Berber regions form certainly part of this memory and heritage. I’ve always sought to engage with the life of Berber women belonging to the generation of my mother and to give life to the beauty and creativity of these women often hidden behind the mashrabiyyahs. Through my art, I wanted to pay tribute to these women who, like my mother and despite the fact that they did not have the chance to go to school under French colonization, managed to transmit to their children the values of tolerance and respect and the spirit of freedom and to ensure that their children—especially their girls—went to school. My work is a feminine writing or what the French call an écriture feminine. I naturally express theses memories of womanhood in which I bathed as a child.

Samta Benyahia / View of 'A Life in Sequins' installation, Roger Quillot Museum, France, 2003 / Courtesy of the Artist

Samta Benyahia / View of 'A Life in Sequins' installation, Roger Quillot Museum, France, 2003 / Courtesy of the Artist

In 1990, just before returning to France from a vacation in Algeria, my mother gave me a black and white photo of herself; it was an enlargement of a passport photograph. Her gesture had something very strong and solemn about it. Two years later, when I was invited by the Brigitte March Gallery in Stuttgart to participate in the 'Force Sight' project, I introduced the portrait of my mother into an installation for the first time. The rosette pattern seen on my mother’s dress was the guiding thread and also the trigger of the emergence and following prevalence of the blue rosette in my work. I found this geometric figure that is popular in Arab-Andalusian art listed under the name of a woman, Fatima. For this reason, it became in my work the symbol of mashrabiyyah and, more generally, a visual metaphor for women. It’s a recurring element. However, through it, I’m talking about women everywhere around the world—and not just North African women—and the idea of circulating this image is not limited to a certain geography. I'm not interested in folklore, but rather in telling a universal story. The Fatima stands for all women and their integration into history. I believe that this integration is necessary for a better world to come about.

Samta Benyahia / Installation view, 'In the Light of Morning,…Albert Camus', Gallery Martine et Thibault de la Châtre, Paris, 2008 / Courtesy of the Artist

Samta Benyahia / Installation view, 'In the Light of Morning,…Albert Camus', Gallery Martine et Thibault de la Châtre, Paris, 2008 / Courtesy of the Artist

If one is not optimistic, one stops. Fortunately, as long as one has life and a means of expression, one remains optimistic. There is the hope of carrying something within whose light will be taken up by others. Dialogue and exchange are very important to the artist. Communication technologies and travel have effectively become elements that are part of the process of art making. From North to South, from East to West, we travel the world. Now, does art have an effect on the world? Yes and no…, but it contributes something and even if it is only a drop, it is important. All art always ends up emitting light, like a star offering its glow to the dark night. Also, visual arts, music, theatre and cinema create through the dreams they provide balance for human beings. They provide a distance from ourselves and the world that helps us to live and sometimes also to say no, enough! Without optimism, one cannot advance.

Samta Benyahia / Installation view of Arabesque sur Seine, Centre Culturel Max Juclier_France_2013 / Courtesy of the Artist

Samta Benyahia / Installation view of Arabesque sur Seine, Centre Culturel Max Juclier_France_2013 / Courtesy of the Artist

I think this simplicity is intuitive. I’ve always felt comfortable with that which is simple. To say things well is, for me, to say them simply. For me, this approach keeps me on a path that feels clear and true. My work is a personal writing—on time and in time—of signs transmitted by various means: engraving, painting, photography, or photocopying... The means are very simple. This simplicity coupled with the equally central aesthetic strategy of repetition is rooted in the memory of my childhood and the place where I was born. Through this personal writing or narrative, the artist attempts to address important topics he or she encounters, tracing a way between subjectivity and the much larger domain of society or the world. It is this continual tension that allows me to reach the essential and the very essence of the sign.

I used to watch women produce their art, preparing, for example, extraordinary trousseaus of great refinement and precision. All of this was transmitted to me. I have never embroidered nor prepared a bridal trousseau but the mediums and aesthetics involved have become means of expression in my own art. I remember very well my mother and my aunt’s loom which, by itself, was already an installation. Watching the beams of light wash over it, this is already art for me. There was always a concern of beauty. I remember the golden carpets woven by my mother and my aunts as well as the architecture of the traditional houses that also informs my practice. It is not only my installations which are related to architecture but also the design of each of my exhibitions where I really take into account all aspects of the space: the width of the ground, the height and color of the walls, etc. I'm always looking for balance and harmony.

Is it from all of these early memories that comes my love of art and the influence of architecture on my work? Maybe and no doubt, at least in part… Observing the transmission of these art forms led me naturally to reflect on this rich cultural heritage and has guided me in my artistic research and practice.

Samta Benyahia / Installation view of Arabesque sur Seine, Centre Culturel Max Juclier_France_2013 / Courtesy of the Artist

Samta Benyahia / Installation view of Arabesque sur Seine, Centre Culturel Max Juclier_France_2013 / Courtesy of the Artist

Thank you too.

Comments

Add a comment