An interview with multi-disciplinary artist Anila Quayyum Agha Testament to the Symbiosis of Difference

Mar 04, 2014 Interview

The portrait of the Artist / Courtesy of the Artist

The portrait of the Artist / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha is a multi-disciplinary artist; creating artwork that explores global politics, cultural multiplicity, mass media, and social and gender roles in our current cultural and global scenario. As a result her artwork is conceptually challenging, producing complicated weaves of thought, artistic action and social experience. Born in Lahore, Pakistan, Agha holds an MFA in Fiber Arts from the University of North Texas. Her work has been exhibited in over 12 solo and 40 group exhibitions. In 2005, Agha was an Artist in Resident at the Center for Contemporary Craft, Houston. In 2008 she relocated to Indianapolis to teach Drawing at the Herron School of Art in Indianapolis. In 2009 Agha was the recipient of the Efroymson Arts Fellowship. She has also received an IAHI grant (2010) and a New Frontiers Research Grant (2012) from Indiana University. This year Agha received the Creative Renewal Fellowship awarded by the Indianapolis Arts Council.

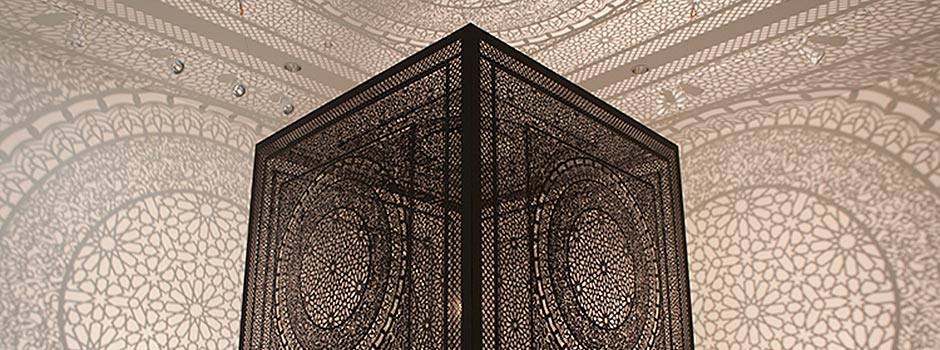

Anila Quayyum Agha / Intersections, detail / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / Intersections, detail / Courtesy of the Artist

Ideas drive the use of process and media in my art making. And the skill and use of craft is very important to me. I think it's because I come from a part of the world where traditional craft skills were mostly the domain of women ensuring them some small measure of independence and recognition. Initially it was a natural way for me to express myself. Over time I noticed that the use of craft, elevated my concepts. Later the usage of crafting techniques & skills progressively gained more importance within my art practice. Now every installation or series of drawings I make have some form of skilful crafting technique associated with it.

I think art is very subjective to each persons' personal experience, taste, knowledge and current fad that may be sweeping the art world. During my travels in the last decade I have been privileged to see a great deal of high quality art and architecture. In my opinion contemporary art practices often use materials and processes in service to concept which may be considered by the general public to be lacking or devoid of exacting craft skills. I however believe there is a tremendous amount of skill employed in contemporary artwork which may not be immediately apparent to untrained eyes. I am always impressed with the artistic abilities that are demonstrated by artists from myriad locations, and of varying qualifications and training.

My personal history and memories of growing up in Pakistan as a woman where cultural traditions and not common sense drive behaviour patterns are a part of my narrative and thus a part of my art making process. Having lived on the boundaries of different faiths such as Islam and Christianity, and in cultures like Pakistan and the USA, my art is deeply influenced by the simultaneous sense of alienation and transience that informs the migrant experience. This consciousness of knowing what is markedly different about the human experience also bears the gift of knowing its core commonalities and it is these tensions and contradictions that I try to embody in my artwork. Through the use of a variety of media, from large sculptural installations to embroidered drawings I explore the deeply entwined political relationships between gender, culture, religion, labour and social codes. In my work I have used combinations of textile processes such as embroidery, wax, dyes, and silk-screen printing along with sculptural methodologies to reveal and question the gendering of textile work as inherently domesticated and excluded from being considered an art form.

My experiences in my native country and as an immigrant here in the United States are woven into my work of redefining and rewriting women’s handiwork as a poignant form of creative expression. Using embroidery as a drawing medium I reveal the multiple layers resulting from the interaction of concept and process and to bridge the gap between modern materials and historical patterns of traditional oppression and domestic servitude. The conceptual ambiguity of the resulting patterns, a theme also represented in the large projects I have created over the years, create an interactive experience in which the onlooker’s subjective experiences of alienation and belonging become part of the piece and its identity.

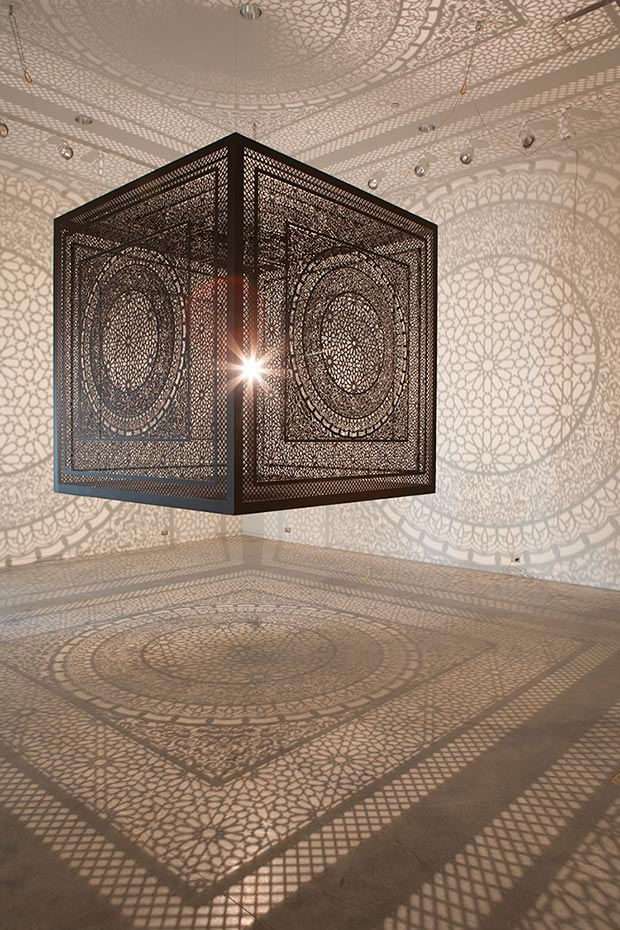

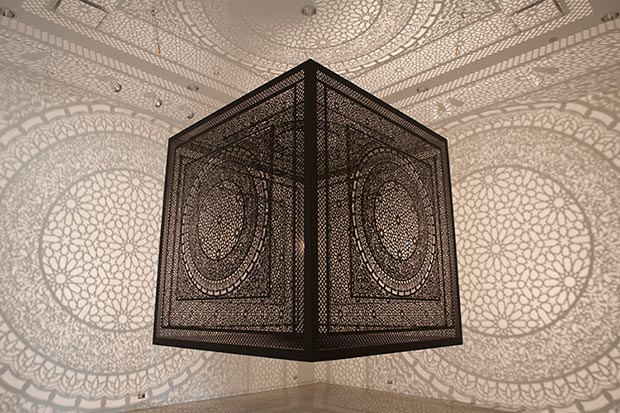

In the ‘Intersections’ project, the geometrical patterning in Islamic sacred spaces, associated with certitude is explored in a way that reveals its fluidity. My goal — as with all my work — is to invite the viewer to confront the contradictory nature of all intersections, while simultaneously exploring boundaries. Through this project my goal was to explore the binaries of public and private, light and shadow, and static and dynamic by relying on the purity and inner symmetry of geometric design, and the interpretation of the cast shadows.

Anila Quayyum Agha / Intersections, installation view / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / Intersections, installation view / Courtesy of the Artist

In the city of Lahore, where I grew up, the mosque was not only a place of worship, but also the repository of the public art form. Thousands of mosques were spread all over the city, filled with bouquets of calligraphic writing and geometric symmetry that embrace pilgrims five times a day. But like the millions of women in Lahore, there was no space for me in any of these mosques, the dictates of culture relegating us all to praying at home. It is this seminal experience of being excluded from a space of community and creativity that resonated with me when I recently visited Moorish Spain. There I experienced the historic site of the Alhambra. And to my amazement discovered the complex expressions of both wonder and exclusion that have been my experience while growing up in Pakistan. My installation emulates patterns from the Alhambra, which was poised at the intersection of history, culture and art and was a place where Islamic and Western discourses, met and co-existed in harmony and served as a testament to the symbiosis of difference.

Cumulatively, this installation uses light, and pattern along with the palpability of reflection to question the assumptions of geometric design as a form opposite to representational or figurative art. The source of this question lies at the crux of Islamic art, which used the geometric form as an example of the pure and transcendent, as opposed to the organic and human. The clean and definite lines and their avowed distance from figurative nature of idolatry aim literally to direct spiritual consciousness away from the ambiguity and corruption of the lived form into the certitude of purity. In exploring the interpretive capacities of the geometric motif, I question this dichotomy that lies at the center of Islamic art and its departure from the human form. In exploring the varieties of interpretation of geometric design, I show the interplay of nature and the created design and its impact on those that perceive it. In this way I question the premise at the heart of Islamic art that the certainty of geometry and non-figurative design, like the certainty of religious text and edict, is not vulnerable or open to myriad interpretations.

Anila Quayyum Agha / Intersections, installation view / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / Intersections, installation view / Courtesy of the Artist

In addition to questioning the assumptions behind the geometric or non-figurative form as certain and static, this piece also provokes an investigation into questions of authenticity, which are central to the post-colonial condition. The intertwining of light and shadow, original and derivative, are at the core of the various renditions of the pattern. They mirror the post-colonial quest for originality and purity an ultimately circular geometric pursuit where primary form can only be imagined and never really captured. The geometric motifs at the center of this pattern are familiar to Islamic audiences around the world because of their reproductions in mosques, monuments and public spaces. In excavating these motifs from the everyday and the humdrum, I also intend to elevate and anoint them as expressions of the ordinary that when attended to and explored, reveal the complexities of symbiosis between cultures and civilizations and the amorphous borders between them. In a contextual milieu where difference and divergence dominate most conversations about the intersection of civilization, this piece explores the presence of harmonies that do not ignore the shadows, ambiguities and dark spaces between them but rather explore them in novel and unexpected ways.

The installation ‘My Forked Tongue’, deals with cultural multiplicity and crossing barriers, whilst traversing our contemporary terrain. Duality is a fact of life for me. In the Sub-continent duality between Pakistan and India goes back generations due to their entwined histories. I grew up speaking Urdu, which is very similar to Hindi, the language spoken in many parts of India. First I am a hybrid of Pakistan and India. Then thirteen years ago settling in the United States complicated matters further. Now there’s a third history entwined with the first two. In my family, we grew up speaking Urdu, Hindi and English which people called Pidgin English, a hybrid language. Furthermore the residue of British colonialism in Pakistan permeates all societal interactions. Inadvertently, due to my language skills I was part of a cultured elite who spoke English flawlessly pointing to class distinctions within the society despite living in poverty. This project came about because of my bilingual abilities and thinking of the stratification of power and class systems.

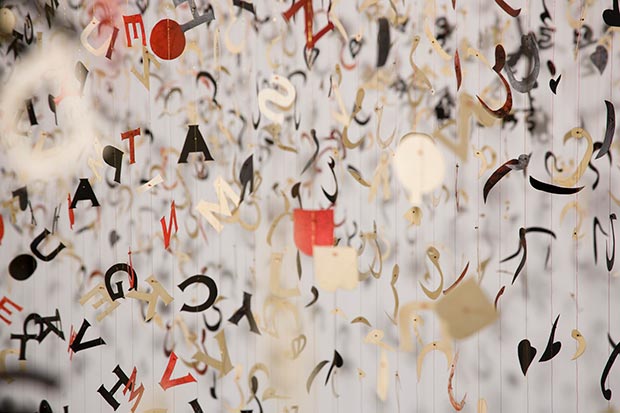

Anila Quayyum Agha / My Forked Tongue II, installation view / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / My Forked Tongue II, installation view / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / My Forked Tongue II, detail / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / My Forked Tongue II, detail / Courtesy of the Artist

This work is comprised of English, Hindi and Urdu alphabets strung on metallic threads interspersed by glass beads. The letters are hand cut paper, uniform in size and waxed for luminosity. The letters from each language are hung in layers, arranged equidistantly from each other creating a seductive pattern in space. The shadows on the walls from the alphabets create new intermingled forms. When hung at different distances from the walls the created shadows change in size and scale, creating a dialogue about memory and history. This installation was my way to aid the audience in contemplation of ideas regarding literacy, cultures and class systems. The craft and labour intensive nature of this piece, both in the making and the installing of the work brings additional points to ponder such as craft versus high art, gender roles and the physicality of the human presence. furthermore the space the installation occupies becomes part of the dialogue. The ability to cross barriers is restricted albeit softly, as the alphabet strings obstruct the navigation of the space, in turn suggesting the difficulty and restrictions faced in crossing boundaries between cultures globally.

Anila Quayyum Agha / My Forked Tongue III, installation view / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / My Forked Tongue III, installation view / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / My Forked Tongue III, detail / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / My Forked Tongue III, detail / Courtesy of the Artist

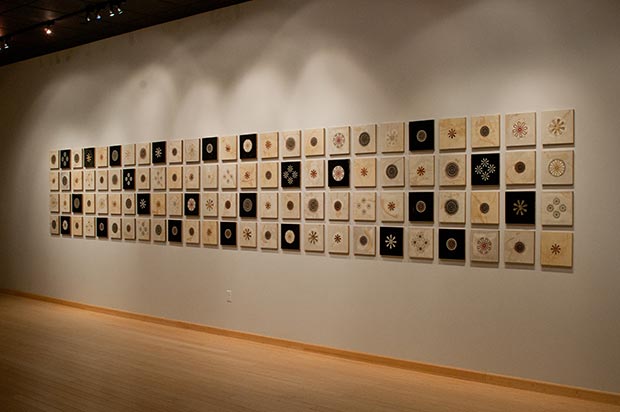

A long ago visit to the Makli Necropolis near the Indus River Delta in Pakistan many years prior to moving to the United States left a lasting impression on me. In 2010, during a visit to Pakistan I re-visited this poignant site which allowed me to examine my romantic memories of the previous visit. The installation ‘Rights of Passage’ uses motifs from the graves of women at this site. For me the designs on the women’s graves at the Makli site evoked the embroidered garments and jewellery worn by women. The repetition of these designs on the clothes worn in life and the graves that marked death evoked the ambiguous boundaries between the two for the women who are subject of adornment. Their lives are light and ephemeral. They come silently and leave silently. Sometimes their only importance in life is their death. In this work, the continuity of adornment thus marks a theme of regularity between female life and death. This piece is homage to those women, the patterns paying tribute to their existence in both reality and memory. The pieces in the installation evoke a memoriam for women and their personal narratives, thus creating beautiful but silent stories within the very essence of the work.

Anila Quayyum Agha / Rights of Passage, installation view / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / Rights of Passage, installation view / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / Rights of Passage, detail / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / Rights of Passage, detail / Courtesy of the Artist

Traditional Islamic art has had some wonderful successes associated with organic and geometric patterns, calligraphy and architecture, as well as skilled craft techniques like wood carving, pietra dura, ceramic tiles and so forth. A success like calligraphy is not easily forgotten and has become the symbolic image for all times to come. Having said that, contemporary artists of the modern Islamic nations have a lot to contribute that may need to have a broader frame of understanding. Societies are becoming more fluid, creating cross-cultural movement. We now live in a post colonialist world where new ideas are constantly emerging, increasing the scholarship about identity & personhood, social and political issues/reforms, and cultural phenomenon. I think, the Islamic world needs to facilitate from within such investigations from artists, historian, philosophers, scientists and others inturn helping to fuel new and cutting edge knowledge and creativity within their societies. I think, often there are self imposed limitations from within the Islamic post colonial cultures based on false morality which cause the cultures to atrophy. I believe just like an enquiring mind, an enquiring culture continues to grow. Conversely if we who are from the Islamic world continue to examine our intentions, reasoning, and responsibilities then the wider world will also follow suit and may and will broaden the frame of understanding.

There have been many artists who have influenced me. The most influential artists for me have often been women artists like Mona Hatoum, Ann Hamilton, Shireen Neshat and Chiharu Shiota. Their artworks are beautifully crafted. But they do much more by taking the audience on journey through cultural landscapes that are fraught with tensions and contradictions. They have not shied away from looking at controversial current and past histories. I have also found wonderful insights by looking at Frances Alys and Antony Gormly's artwork. Furthermore, artists from Pakistan like Shahzia Sikandar and Imran Qureshi are making excellent work which gladdens my heart. I find, artwork that allows viewers to examine shifting identities, the politics of cultural landscape and the examination of public and private space very compelling. Such work allows me to stand up and be represented myself as a citizen of the world.

Its a busy year already and it has barely started. I am currently working on a new installation that involves 5000 actual thorns that I harvested from the honey locust trees in Texas reminiscent of the berry trees from Pakistan. I furthermore have a full teaching load at Herron School of Art & Design for the 2014 academic year as well as leading a summer student trip to Spain with a colleague. Right after the trip to Spain I am heading to Japan for the first time with the support of the Creative Renewal Fellowship I received last year from the Indianapolis Arts Council. During this trip I intend to experience the Japanese culture, with a visit to Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto, and Nara and hopefully connect with artists and crafts people. I have been inspired by Japanese artists like Chiharu Shiota and architects for creating installations and architecture where space is active yet elegant, traditional yet innovative and best of all simple but not simple minded. Visiting Japan will help give my fascination with Japan a first hand context, which will urge developments in the conceptual elements of my own artwork. Lastly I am scheduled to have two exhibition this year, first one at the 924 Art Gallery, a first solo show in Indianapolis, and the second at the Sheldon Swope Museum in Terra Haute, Indiana in the fall of 2014. Last but not least, I am currently in the process of sending out multiple proposals to exhibit the Intersections installation to national and international venues. This process is long and intense and requires a lot of dedication and the ability to deal with rejection.

Anila Quayyum Agha / The honey locust trees, installation view / Courtesy of the Artist

Anila Quayyum Agha / The honey locust trees, installation view / Courtesy of the Artist

Thank you for asking me to talk to you and through you to your readers. I appreciate it very much. Many thanks.

Comments

Add a comment