An Interview with Pakistani Artist Aisha Khalid The Divine is in the Detail

Oct 27, 2013 FEATURE, Interview

Aisha Khalid is not only one of the best-known artists in present-day Pakistan. She is also listed by Newsweek as amongst the most influential women in the country. A graduate of Lahore's National College of Arts' well-known miniature painting program, Khalid has pushed the medium to new limits, developing a unique recognizable style that simultaneously evokes Islamic ornamentation, traditional textile arts, and modernist abstract painting. The artist also works with video, installation and actual textiles. Khalid's art, regardless of medium, combines an almost obsessive meticulousness with a powerful, often spiritual, presence. If some work treats particular political issues, every piece Khalid produces effects change through its sheer visual beauty. Her increasingly non-narrative images possess the same resonance and depth as the best Islamic art.

Pakistani Artist Aisha Khalid / Courtesy of the Artist

Pakistani Artist Aisha Khalid / Courtesy of the Artist

I am formally trained as a miniature painter. Treading the thin line between the demands of the discipline and the wish to break away from its conventionalities was the focus of my initial work. My work, however, is mostly based on my life experience and surroundings. For example, it took a sharp turn after the difficult experience of losing a family member in 1999. My imagery such as the veil, the curtain and floral patterns come from textiles for which I have a great interest. My love of geometric pattern stems from the tiled floor of my old house in which I spent my childhood. And the veil comes from my family. My father was a landlord in Sind and, in this particular environment, my mother wore a veil, and I wore a chaddar (big shawl) when I went to school. So the veil was initially a positive symbol in my work. I saw it as a source of protection.

Later, I portrayed it as a sign of oppression; I made it blue and painted eyes on it to signify the male gaze. But I was not simply trying to critique men or the society here - my interpretation was more complicated than that. It functioned as a self-portrait in which the burqa was a source of shelter, but I portrayed it simultaneously as something oppressive to women. And then, when I did a residency in Amsterdam at the Rijksakademie in 2001, it changed again. I switched the position of the burqa in my work, depicting it no longer from the back but from the front because of the shift of the world's attention to the veil and Islam. So the veil became even more prominent in my paintings. It began to serve as a symbol of identity more than of religion: it acquired the significance of an entire culture's identity. I continue to use the burqa in my art, but it has evolved over time and it now appears in very minimal form, where you just see the hemline of the veil or curtain.

The tulip appeared in Amsterdam and came to symbolize Western women. The tulip, even if it is native to Central Asia, is associated with Holland and Dutch history; tulips were expensive and considered very precious in Europe. Before that, I was working with the lotus flower and the rose. The flower motifs found in my paintings are also rooted in the love of textiles that I inherited from my mother. In fact, I originally planned to study textile design rather than painting. My visual vocabulary and color schemes are also grounded in Mughal miniature painting which is what I studied. I've worked for the last fifteen years in the medium. But my personal life, travelling and world events also affect the work. For example, bright colors disappeared after 9/11 and, for several years, I worked only in the green and khaki tones of army camouflage. So changes are connected to what is happening with me. The work evolves. It has gotten gradually much bigger over time, been nourished by doing in situ installations and so on.

Aisha Khalid in the process of painting / Courtesy of the Artist

Aisha Khalid in the process of painting / Courtesy of the Artist

My work is all about the process. It's very labor intensive. It's like a meditation. Process is everything whether I'm painting, embroidering pieces for an installation or adorning jackets with gold pins. What transpires from the work is because I enjoy making it. You can only achieve beauty when you experience the lengthy time and process as soothing, peaceful and spiritual and not as laborious. Repetition is also a critical aspect of how I make my work. Because it helps in the act of meditation, it is a necessary part of the process. For me, that is everything - the act of making. In the end, something gets made; however, I really enjoy the whole process and that is the most critical thing. And I think without entering a meditative state, I wouldn't be able to make a piece like 'Kashmiri Shawl' that included over three hundred thousand pins. So you can imagine inserting one pin, and then the next, and then the next… It’s very similar to the way I paint. And this repetition is related to the direction in which my work is going. My work is personal, of course, but, more specifically, it is about my spiritual experiences and my love of God.

I really enjoy the process of making art. I'll just sit down and begin and I won't even notice that hours have passed. I might sit for five hours and then take a break. Sometimes, I work for ten to twelve hours in a day. It's not really work for me; it's something else. It's like a blessing. You're doing it for yourself, fine, it gets exhibited afterward, but you get out of it what you need.

Aisha Khalid / The Divine is in the Detail, Installation view / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / The Divine is in the Detail, Installation view / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

I talk about political issues and other concerns through beauty and in a poetic manner. Not everything is political, but an occasional work emerges that does deal with politics directly. Take, for example, 'Kashmiri Shawl' made for the Sharjah Biennial that explored the current events in Kashmir. The Kashmiri shawl is such a prized possession. Whenever we ask anyone outside of Pakistan what we should bring for them, the request is always for a shawl. And so I wondered about this phenomenon: that there was such a fascination for these shawls but there is no concern or even awareness of what's going on in the country.

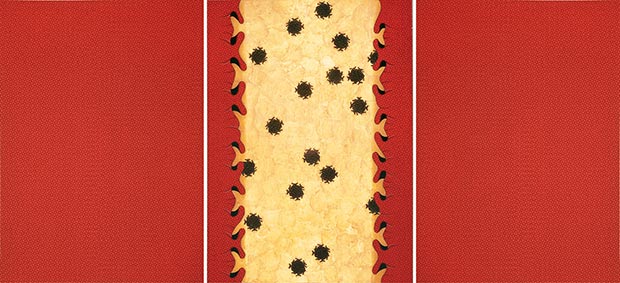

My work is both personal and political, but when I am asked to do something site-specific, it's usually more overtly political. For example, in 'View Point' that I did in 2008 at the Bagh-i Babur in Kabul, I placed stylized bullet holes on the walls and floor to speak about the violence and pain of the region. In the 2009 Venice Biennale installation 'Face It', I positioned the images of holes on a mirror to engage and implicate Western viewers. When they looked into the mirror, their own bodies would appear wounded; the idea of war was further suggested by the use of red and camouflage pattern. In Karachi, I created a visually confusing space using multiple mirrors to symbolize the uncertainty that clouds the city, as well as country. It was meant to be a quiet space to retreat to from the chaos of the city. Even though these installations possess a very strong political dimension, in all of them, I was still also exploring formal issues and experimenting with the boundaries of miniature painting.

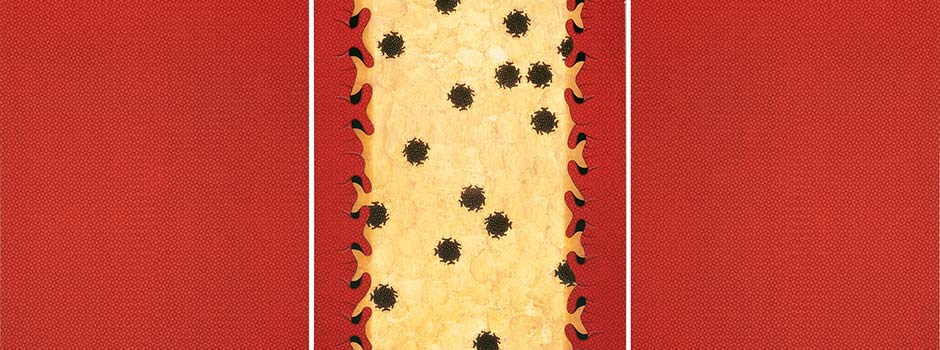

To get back to the question, the 'West Looks East' paintings are about two different ends of the world which cannot meet, about two cultures that are very different from each other. For centuries, the West has been looking at the East with vested political and economic interests and it has always been accompanied with war.

Aisha Khalid / West Looks East, 2013. Gouache on wasli paper. Diptych, 69.8 x 50.8 cm / 27.5 x 20 in. each panel, overall 69.8 x 101.6 cm / 27.5 x 40 in / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / West Looks East, 2013. Gouache on wasli paper. Diptych, 69.8 x 50.8 cm / 27.5 x 20 in. each panel, overall 69.8 x 101.6 cm / 27.5 x 40 in / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / West Looks East, 2013. Gouache on wasli paper. Diptych, 69.8 x 50.8 cm / 27.5 x 20 in. each panel, overall 69.8 x 101.6 cm / 27.5 x 40 in / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / West Looks East, 2013. Gouache on wasli paper. Diptych, 69.8 x 50.8 cm / 27.5 x 20 in. each panel, overall 69.8 x 101.6 cm / 27.5 x 40 in / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / West Looks East, 2013. Gouache on wasli paper. Diptych, 69.8 x 50.8 cm / 27.5 x 20 in. each panel, overall 69.8 x 101.6 cm / 27.5 x 40 in / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / West Looks East, 2013. Gouache on wasli paper. Diptych, 69.8 x 50.8 cm / 27.5 x 20 in. each panel, overall 69.8 x 101.6 cm / 27.5 x 40 in / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

My work is inspired by Islamic geometry and designs and, if you follow its trajectory, you will notice how my use of pattern has evolved. It's now shifting into something else. At first, there was a one-point perspective within a limited, claustrophobic space. After a while, a circular form emerged in my work. And now, there is an infinite space. Repetition is inherent to pattern and constitutes a critical aspect of how I make the work.

Islamic art and geometrical pattern have influenced my work more directly since 2007. In making the pieces more visibly inspired by Islamic infinite pattern, I realized that nothing is useless in this art form. Everything is Sufi-inclined and spiritual. And so the geometry and mathematical dimension of my art are coming from Islamic art, as is the choice and application of color. The essence of Islamic art - which is a spiritual art - is mathematics, color and repetition. Mughal art is, of course, Islamic art too. Geometrical and floral patterns are seen here in the jali screens and architectural decoration. The beauty of Islamic art is in my genes. In this sense, my work owes more to my mother than to art school.

When I first started working with the veil, it was different. In my early works, the veil actually depicted a traditional form of female covering and served as both a form of self-representation and a way to address female roles and stereotypes. However, it's no longer a physical veil. Rather, the veil in my paintings is now a poetic or metaphorical sign. As in Islamic mystical poetry, it evokes not gender issues, but the veil between Allah and humans or else the unveiling of the heart or kashf that allows people to see beyond physical reality. It speaks of the hope, surprise and presence behind it.

Aisha Khalid / Installation view / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / Installation view / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

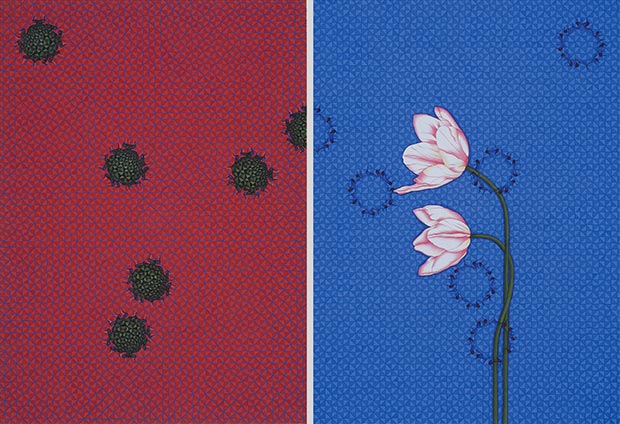

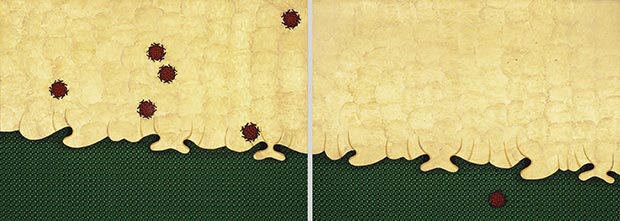

Aisha Khalid / Wound is a Place Where Light Enters You, 2013. Gouache and gold leaves on paper board. Diptych, 83.8 x 115.5 cm / 33 x 45.5 in. each panel, overall 83.8 x 231 cm / 33 x 91 in / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / Wound is a Place Where Light Enters You, 2013. Gouache and gold leaves on paper board. Diptych, 83.8 x 115.5 cm / 33 x 45.5 in. each panel, overall 83.8 x 231 cm / 33 x 91 in / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

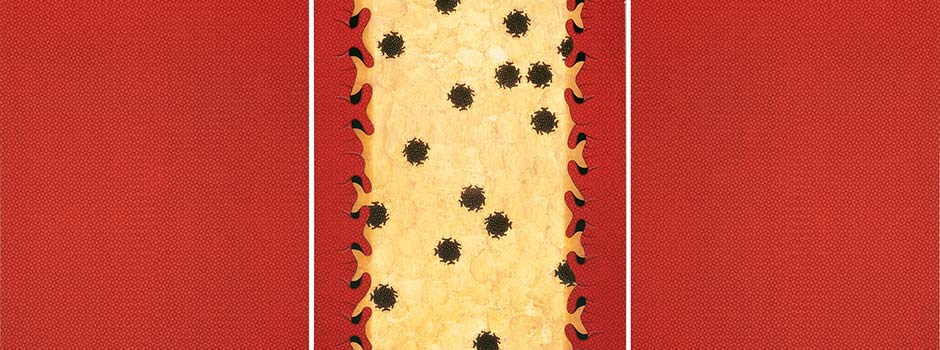

Aisha Khalid / Wound is a Place Where Light Enters You, 2013. Gouache and gold leaves on paper board. Triptych, 116.8 x 82.5 cm / 32.5 x 46 in. each panel, overall 116.8 x 247.5 cm / 32.5 x 138 in / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / Wound is a Place Where Light Enters You, 2013. Gouache and gold leaves on paper board. Triptych, 116.8 x 82.5 cm / 32.5 x 46 in. each panel, overall 116.8 x 247.5 cm / 32.5 x 138 in / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / Installation view / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / Installation view / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

My life and art are interconnected. My interest, before I started painting, was in textiles and they first entered my art in the guise of veils, curtains and tablecloths, and pattern more generally. I enjoy textiles in all their forms. Plus, I like doing things with my hands like knitting, embroidery and sewing, so it's normal that textiles themselves became a medium. 'Yourself of Yourself' is about pain, about the good things that come from pain. Spirituality goes together with pain. When God takes something from you, He rewards you with something else. It also shows the two sides of the human personality: inner and outer, or spiritual and metaphorical.

Aisha Khalid / Yourself Of Yourself, 2013. Fabric and needles. Diptych, 88.9 cm / 35 in. length / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / Yourself Of Yourself, 2013. Fabric and needles. Diptych, 88.9 cm / 35 in. length / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / Yourself Of Yourself, Installation view / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

Aisha Khalid / Yourself Of Yourself, Installation view / Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

'Conversation', the two-channel video installation that I produced in Amsterdam, also incorporates elements of sewing, embroidery, and repetition. In one video, viewers see my hands embroidering a rose. In the other, they see those of a white woman who repeatedly undoes every stitch I've just made. By the end of the video, I've completed a whole red rose, while she has undone it completely.

Comments

Aug 23, 2017 - 10:50:26

Your article is really impressive.

Add a comment