An Interview with Jennifer Heath, Writer, Activist and Curator The Veil: Visible and Invisible Spaces

Dec 09, 2012 Interview

Jennifer Heath is an independent scholar, award-winning cultural journalist, critic, curator, and activist. Her most current exhibitions are “The Veil: Visible & Invisible Spaces,†which has been touring the United States since 2008 and “Water, Water Everywhere: Paean to a Vanishing Resource,†which began traveling this year - http://waterwatereverywhere-artshow.com/. Others include the renowned “Black Velvet: The Art We Love to Hate.†She is the author of eleven books of fiction and non-fiction, including The Veil: Women Writers on its History, Lore, and Politics (see www.theveilbook.com) and Land of the Unconquerable: The Lives of Contemporary Afghan Women (with Ashraf Zahedi) both published by the University of California Press. Children of Afghanistan: The Path to Peace (with Ashraf Zahedi) is forthcoming from the University of Texas Press, and her collection, The Jewel and the Ember: Love Stories from the Islamic World, is currently under consideration. Future art exhibitions include “The Map is Not the Territory: Parallel Paths-Palestinian, Native American, Irish,†to launch at The Jerusalem Center Gallery in September 2013.

I love that you say “unpack the veil†– because that is precisely what we’re doing. Unpacking the history and the universality of the veil and veiling practices, so as to bring it to light, engage received wisdom and challenge stereotypes. My motivations are complex, even somewhat convoluted, but in a nutshell, I grew up in veiling cultures –both heavily Roman Catholic and Muslim– and thus know from experience that what the West perceives as the whys and wherefores of veiling –primarily oppressive, antiquated customs of the “Otherâ€â€“ are often distorted. I wanted to dispute those notions. This is also why I wrote The Scimitar and the Veil: Extraordinary Women of Islam. In order to understand the multiple truths inherent in any issue, and speak those truths to power, we must contextualize. The book, The Veil: Women Writers on Its History, Lore, and Politics (University of California Press, 2008) tackled the veil from as many cultural and historical angles as possible –Islam, Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, various secular and pagan and pre-Abrahamic points of view, male veiling, mourning, the arts– by writers who approached the topic via personal, political and/or scholarly paths. Having had a visual arts, as well as a literary background, I wanted also to see what artists were thinking and doing. And since I am interested in issues of social and environmental justice, I wanted to combat what I perceive as violations of civil liberties and discrimination against veiling practices, particularly in Europe.

Well, we have not yet changed the world, or, say, French laws! But the book and the exhibition have been well-received with many reviews and viewer comments that indicate the projects have been eye-opening, that people did not realize how common, how ancient, how universal veiling really is—and to that end, we hope that viewers and readers can drop their prejudices and look at others more deeply and less fearfully.

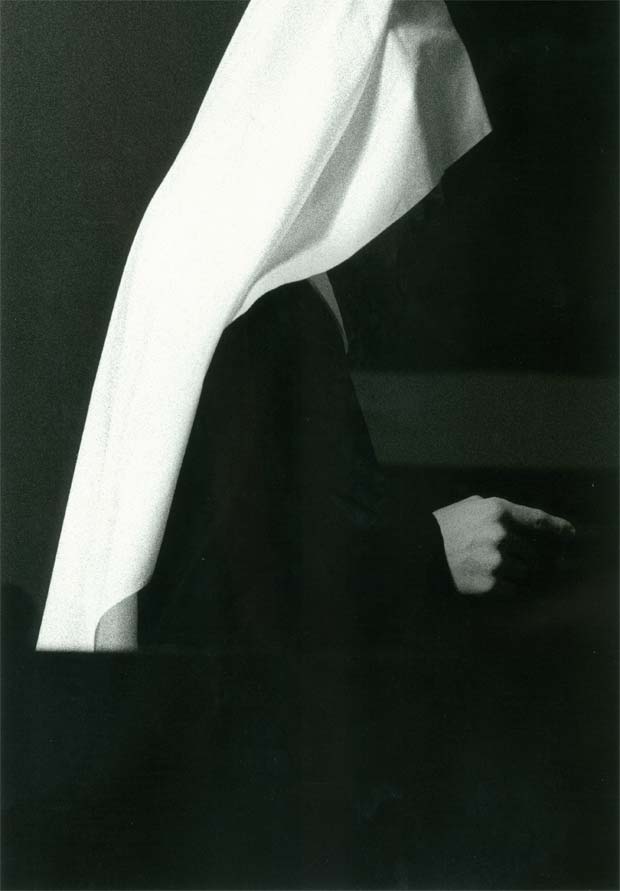

Valari Jack is a portrait and documentary photographer who lives in Boulder, Colorado and who has been involved in photography for twenty-five years. Her images in the show are part of a black and white series executed using only natural light entitled, Quiet Seasons of Grace: A Year in the Life of the Abbey of St. Walburga. In order to do Valari justice, I would like to cite her lovely artist statement and short bio:

“Many years ago, I lived across the road from a community of Benedictine nuns, just outside Boulder, CO. I was fascinated by the sight of a smiling woman wearing a veil and overalls as she drove a tractor over the fields next to a chapel. Within the boundaries of their life as a cloistered religious community and my life as a young mother and aspiring photographer, we got to know each other. I asked if I could photograph their daily lives and with great trust in me, they agreed to let me come with my camera for the Easter rituals. That was the beginning of a defining experience in my life. I spent the next year documenting the seasons of their religious and farming activities. In that year, young women came to test their vocation to monastic life, and stayed or left. Christmas was celebrated. Calves were born in freezing spring snowstorms. The Divine Office was chanted six times a day, every day, in the chapel. The first Mother Superior died at a great age. The Easter Vigil told the story of death and resurrection with a dark chapel transformed by a sequence of candles, newly lit. Young nuns used skateboards to hurry from chapel to the barn. Corn was irrigated in summer heat. All time was sacred and circular and life was eternal. And the veil was worn as a reminder, to both the wearer and the observer, of the choice to live apart from secular life and committed to God.â€

Valari Jack, “Sister Linda at Vespers,†detail from Seasons of Grace: A Year in the Life of the Abbey of St. Walburga, 1988-89, silver gelatin photograph / Courtesy of Jennifer Heath

Valari Jack, “Sister Linda at Vespers,†detail from Seasons of Grace: A Year in the Life of the Abbey of St. Walburga, 1988-89, silver gelatin photograph / Courtesy of Jennifer Heath

Let me say first that I definitely did not want to do a documentary, a sort of National Geographic exhibition. I am not interested in portraying exoticism. Nor was I interested in doing a costume show.

Of course, as you and your readers well know, art is more these days than painting and sculpture, so naturally, I looked to various media, each of which has a different mode and effectiveness of expression, equally essential in conveying ideas and information. I can’t really describe my vision except as I tried to earlier, and my guiding instinct is quite completely beyond me. Instinct is really the right word. It’s almost all intuition. And then, of course, I think about whether a particular work is meaningful to the bigger picture I want to describe. My eyes, as they say, are often bigger than my stomach – I tend to want to make large exhibitions, because I can’t stop and I seem to fall in love with so many works!

In selecting artwork, I tried to follow more or less the thoughts set forth in the book. But I often went through odd labyrinths to do so. Just for one example, I had a conversation with scholar Margot Badran, which I recorded in my book introduction, wherein Dr. Badran spoke of the Egyptian feminist, Huda Shaarawi’s “first unveiling†on paper meaning writing her memoirs. That brought me to invite the artist Tiffany Besonen to submit her work, i am water, created on translucent dress-pattern paper, featuring a poem by LuAnn Muhm: “I am smoke/when I can be/More often/ I am water/In the shape/of my container.†For me, it all fit together – the contents of the poem itself, the fact of writing, the paper that is also attire-in-waiting.

Of course, finding art these days is made relatively easy with the Internet and social media, which spread the word fast. One writer for the book was truly instrumental in spreading the word. Désirée Koslin who wrote the chapter on veiling in medieval Europe and the Early Church also happens to be a visual artist. A retired from teaching at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, she put out the call through Soho20, a woman’s collective in Manhattan with artist members all over the United States.

Tulu Bayar is a Turkish-American artist, teaching at Bucknell University in Pennsylvania. She works primarily, I believe, with photography and video. Confluence is a two-channel magnificent dialogue, reflecting on issues of veiling particularly evident in Turkey (though elsewhere, too). The women in the film trade the headscarf, back and forth, screen to screen, interpreting and reinterpreting the body, the covering, their hair, sacred space. In addition to the cloth, the two women – each confined to her own frame – experiment with a wig. I understand that many observant Turkish women who wish to veil, but in various circumstances are disallowed, have taken to wearing wigs, much in the same spirit as Jewish women of Hasid tradition. Naturally, I also found that element of Confluence appealing – again pointing to commonalities.

Tulu Bayar, film still from Confluence, 2005, DVD (Elvira woman veiled and unveiled) / Courtesy of Jennifer Heath

Tulu Bayar, film still from Confluence, 2005, DVD (Elvira woman veiled and unveiled) / Courtesy of Jennifer Heath

I first saw Swiss-Tunisian artist Fatma Charfi’s Another Space as live performance in about 2000 and in The Veil it is a looped slide show. The artist affixes to the veils she uses in the performance tiny tissue-paper figurines that she models after a special Tunisian bread-making technique. She calls them Abroucs, a Tunisian term describing someone clever, shy and also ludicrous. They are guides, she says, between the modern and the ancient, faceless, genderless shadows. It is somewhat abstract, yet evokes – to me -- images of brides and fertility, as well as protection and prophecy.

Fatma Charfi, detail from Another Space, 2000 performance (slide show) / Courtesy of Jennifer Heath

Fatma Charfi, detail from Another Space, 2000 performance (slide show) / Courtesy of Jennifer Heath

Dressing, costuming, attiring ourselves – even alone before the mirror, even as a private act is performance. We make choices and tell stories consciously or unconsciously in this performance.

Mary Tuma is a Palestinian-American artist and Homes for the Disembodied was originally created for a spectacular show called Made in Palestine. She writes that it is “a memorial to and offering for the Palestinian people displaced from Jerusalem who were unable to return to their homes before their deaths.†She made the piece in Jerusalem in 2000 from fifty continuous yards of silk. It is important for her that the dresses are made from a single continuous piece of fabric because it serves as a metaphor for the bond uniting the Palestinians created in part through their shared misfortune. For Tuma, the monumental scale of the dresses is a testament to the strength of the women who she says “must carry on in unjust circumstances, they have little power to change….†while the emptiness refers to how home is part of the imaginary not just geography. Again to quote the artist: “Whether or not she is seen in Jerusalem, she is there, in spirit, veiled.†I put Homes for the Disembodied in the show, because, among other things, it represents another kind of veiling – that of hidden communities, neglected and ignored.

Mary Tuma, Homes for the Disembodied, 2006, 50 continuous yards of silk / Courtesy of Jennifer Heath

Mary Tuma, Homes for the Disembodied, 2006, 50 continuous yards of silk / Courtesy of Jennifer Heath

Absolutely. Think of the comedy tour, “Allah Made Me Funny.†Suddenly, we all become human together, dissolving in laughter…dissolving our differences. I have always thought that the only way to survive is to try to stay as amused as possible, despite the tragedy, and to remember, as the late historian Howard Zinn wrote, “To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness. What we choose to emphasize…will determine our lives.†Humor is a sign of hope. And certainly of compassion and courage and wisdom.

Incidentally, I have been invited several times to re-curate smaller versions of The Veil: Visible & Invisible Spaces but, unfortunately, I was not aware of Kate’s Flying Burqas until after the larger, original show had hit the road. I regret this terribly. She is an extraordinary artist. At least Flying Burqas could be featured in a satellite veil show at Concordia College in Minnesota. I hope I can use her work again somewhere, someday.

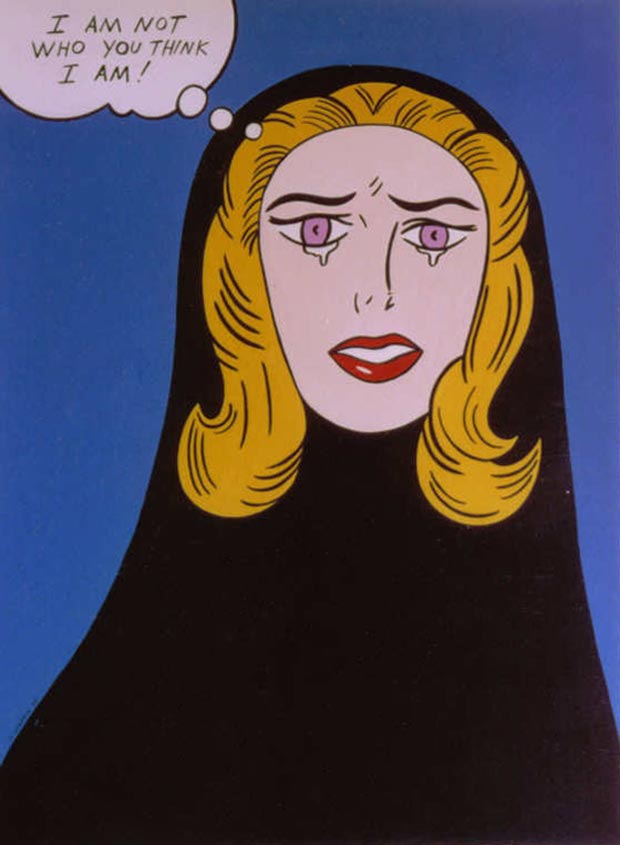

Helen Zughaib, “Abaya Lichtenstein,†detail from Secrets Under the ‘Abaya, 2005-2006, gouache on board / Courtesy of Jennifer Heath

Helen Zughaib, “Abaya Lichtenstein,†detail from Secrets Under the ‘Abaya, 2005-2006, gouache on board / Courtesy of Jennifer Heath

It’s exciting to me that the exhibit looks slightly different in each gallery. Some galleries have more flexibility, more space, more equipment – for projecting DVDs, for instance – so installations are varied. One museum painted the walls a ocre-ish yellow for the show. I was stunned – it was dazzling. And I’m always almost as happy to see The Veil each time I’m invited to do a gallery talk as I am to see my children after an absence. But, no, I don’t add to it or take anything away. There’s too much preparation involved – crates, carefully built to fit the work, written materials, wall texts, and so on. It would be impossible to alter it. But that’s a nice part of being privileged to re-curate The Veil. I can feature new additions like Kate Hamilton’s Flying Burqas, and therefore kind of re-contextualize whatever work from the original show that I can repeat (prints, DVDs e.g.).

I require that all the galleries make available a viewer comment book and send them to me when the show is over, along with installation images, condition reports and that kind of thing. Forgive the way this sounds, but we have only had two unhappy comments in four years. The show has drawn record viewers, the comments are inevitably happy and grateful, expounding on the exhibition’s beauty and how much the viewers have learned. Naturally, I’m very flattered and relieved and happy about it. I send the comments to all the artists each time we receive them. One artist quipped recently that it was “same old same old high praise.†It’s actually a little alarming, now that I think about it.

The last show will be at the Handwerker Gallery at Ithaca College in New York. The plan was always to go through 2013, though I think we’d all welcome another year or so if opportunities arose. Each work is emblazoned in my memory, I really love and admire them all, and I hope to work again in other capacities with many of the artists. Some of the artists were already friends, and some have become friends, as have some of the curators who took the show. I think when it’s over, I’ll have a raging case of what we used to call post-performance blues.

I have just launched a new international traveling exhibition called Water, Water Everywhere: Paean to a Vanishing Resource, which is comprised entirely of new-media work on DVD. Partly, this is because film “feels†like water – the show is predicated on the fact that water is the most crucial issue of our time – and also because of expenses in shipping – sending 45 disks on the road is much easier in these difficult economic times than shipping eight crates of artwork!

I am also working with The Jerusalem Fund Gallery in Washington, D.C., on an exhibition called The Map is Not the Territory: Parallel Paths-Palestinians, Native Americans, Irish. It will be small works on paper, and like The Veil, will grapple with context and commonalities. Such understandings are urgent to me. We can’t change injustice anywhere without seeing the whole picture. These three groups are by no means the only ones who have been oppressed and mistreated, not by a long shot. But these are especially interesting because they have actual relationships to one another, in addition to common histories that have been profoundly meaningful. Jerusalem Fund curator Dagmar Painter and I have put out an artist call and artwork is due to be submitted in January.

Valerie, thank you. I so appreciate the chance to prattle about The Veil and about my work in general. It is truly an honor.

Comments

Add a comment