THE BRITISH MUSEUM New Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World

Oct 10, 2018 FEATURE, Art Collection

Stanton Williams's design for the British Museum's Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World opens the space up to new views and natural daylight. ©Stanton Williams

Stanton Williams's design for the British Museum's Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World opens the space up to new views and natural daylight. ©Stanton Williams

The Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World will be a comprehensive presentation of the Islamic world through art and material culture. Situated within a new suite of rooms at the heart of the British Museum, it will underscore global connections across a vast region of the world from West Africa to Southeast Asia and reflect links between the ancient and medieval as well as the modern worlds.

Islam has played a significant role in great civilisations as a faith, political system and culture. The new gallery will feature objects that give an overview of cultural exchange in an area stretching from Nigeria to Indonesia and from the 7th century to the present day. From cooking pots to golden vessels, and from 20th-century dress to contemporary art, the objects displayed will demonstrate the extraordinary richness of global encounters. The place and role of other faiths and communities including Christians, Jews and Hindus-will be reflected throughout the gallery, showing their significant contributions to the social, economic and cultural life of the Islamic world.

The British Museum's collection of Islamic material uniquely represents the finest artworks alongside objects of daily life such as modern games and musical instruments. The collection includes archaeology, decorative arts, arts of the book, shadow puppets, textiles and contemporary art. The creation of the Albukhary Foundation Gallery provides an extraordinary opportunity to display these objects in new ways that showcase the peoples and cultures of the Islamic world, as well as the ideas, technologies and interactions that inspired their visual culture.

Enamelled glass mosque lamp, c.1330-45. Egypt or Syria. Gilded and enamelled glass. This object is one of a pair of lamps that bear the name of the Mamlukamir Sayf al-Din Tuquzdamur. He was governor of Hama in Syria and Amir of the Assembly (amiral-majlis) for the Mamluk sultan al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalaun (r. 1293-1341) / © The Trustees of the British Museum

Enamelled glass mosque lamp, c.1330-45. Egypt or Syria. Gilded and enamelled glass. This object is one of a pair of lamps that bear the name of the Mamlukamir Sayf al-Din Tuquzdamur. He was governor of Hama in Syria and Amir of the Assembly (amiral-majlis) for the Mamluk sultan al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalaun (r. 1293-1341) / © The Trustees of the British Museum

The great medieval dynasties up to about 1500 are explored in the first room, highlighting connections within nearby galleries relating to Byzantium, the Vikings, the Crusades and Islamic Spain. A 13th-century incense burner made of intricate inlaid metalwork from Damascus combines techniques developed in Mosul, with decoration depicting Christian scenes demonstrating that such objects were made for a variety of patrons both Christian and Muslim. Rarely seen archaeological material discovered at two major cosmopolitan centres will bring to life the inner workings of these early Islamic cities. Samarra in present-day Iraq is a vast palatial city on the banks of the Tigris, and Siraf is a port city on the south coast of Iran. 20th-century excavations yielded an extraordinary richness of material, from 9th-century wall fragments with painted faces to coveted Chinese porcelain traded across the Indian Ocean in journeys echoing the tales of the legendary Sindbad the sailor from the Arabian Nights.

Inlaid incense burner, c. 1250–1300, Syria, probably Damascus. Cast brass, pierced at the top, inlaid with silver. The shape of this incense burner developed from a type popular in the Byzantine period. It is richly inlaid with silver, a legacy of the styles developed in the workshops of Mosul in the early 13th century / © The Trustees of the British Museum

Inlaid incense burner, c. 1250–1300, Syria, probably Damascus. Cast brass, pierced at the top, inlaid with silver. The shape of this incense burner developed from a type popular in the Byzantine period. It is richly inlaid with silver, a legacy of the styles developed in the workshops of Mosul in the early 13th century / © The Trustees of the British Museum

_Egypt_marble_(c)The_Trustees_of_the_British_Museum.jpg) Stone inscription of early kufic script, dated AH 356 (AD 967). Egypt, marble This marble panel is one of four now in different collections that originally made up a cenotaph that was subsequently taken apart and the backs re-carved. The outer face, probably carved in the 9th century, consists of the beginning of the basmala, In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate. The text is in angular kufic script, with some of the letters terminating in elegant leaf forms. / © The Trustees of the British Museum

Stone inscription of early kufic script, dated AH 356 (AD 967). Egypt, marble This marble panel is one of four now in different collections that originally made up a cenotaph that was subsequently taken apart and the backs re-carved. The outer face, probably carved in the 9th century, consists of the beginning of the basmala, In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate. The text is in angular kufic script, with some of the letters terminating in elegant leaf forms. / © The Trustees of the British Museum

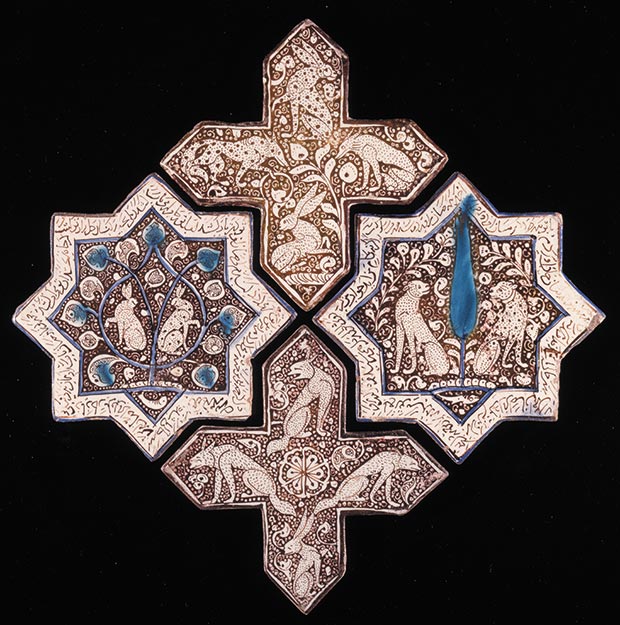

Star and cross tiles, AH 664-65 (AD 1266-67). Iran, probably Kashan. Stone paste, moulded and painted in blue, turquoise and lustre over an opaque white glaze. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Star and cross tiles, AH 664-65 (AD 1266-67). Iran, probably Kashan. Stone paste, moulded and painted in blue, turquoise and lustre over an opaque white glaze. © The Trustees of the British Museum

The_Trustees_of_the_British_Museum.jpg) Astrolabe, AH 638 (AD1240/1). Probably southeast Turkey, northern Iraq or Syria. Brass, silver, copper. Heavily inlaid with silver and copper, this astrolabe features striking figural imagery on its front and back. It is signed Abd al-Karim al-Asturlabi (the Astrolabist) / © The Trustees of the British Museum

Astrolabe, AH 638 (AD1240/1). Probably southeast Turkey, northern Iraq or Syria. Brass, silver, copper. Heavily inlaid with silver and copper, this astrolabe features striking figural imagery on its front and back. It is signed Abd al-Karim al-Asturlabi (the Astrolabist) / © The Trustees of the British Museum

The second room introduces the three major dynasties dominating the Islamic world from the 16th century: the Ottomans, Safavids and Mughals. Their patronage saw the production and trade of magnificent objects, including ceramics, jewellery and painting. A new approach in this gallery is to also include 19th- and 20th-century objects and textiles from Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, and South and Southeast Asia, many of which have not been displayed before. From elaborate 19th-century mother-of-pearl inlaid wooden Turkish bath clogs to a brightly decorated Uzbek woman's robe with Russian lining, juxtapositions of objects will continually draw attention to the cross-fertilisation between regions and time periods.

Uzbek woman's ikat coat with Russian lining. 1870-the 1920s, cotton and silk. High-quality silk robes served as status symbols and were worn in layers for added ostentation. A woman would have worn this robe (munisak) over a dress and trousers during important rites of passage, from weddings to funerals. It is woven with stylised horns and pomegranate flowers, symbols of strength, abundance and fertility / © The Trustees of the British Museum

Uzbek woman's ikat coat with Russian lining. 1870-the 1920s, cotton and silk. High-quality silk robes served as status symbols and were worn in layers for added ostentation. A woman would have worn this robe (munisak) over a dress and trousers during important rites of passage, from weddings to funerals. It is woven with stylised horns and pomegranate flowers, symbols of strength, abundance and fertility / © The Trustees of the British Museum

_The_Trustees_of_the_British_Museum.jpg) Alhambra tile, late 14th century, Malaga or Granada, Spain. Earthenware painted over and incised in an opaque white glaze. This tile was acquired from Alhambra in1791by a traveller to the site. The Nasrid rulers were responsible from 1232 for the construction of the Alhambra in Granada, one of the best-known examples of Islamic architecture in the world. / © The Trustees of the British Museum

Alhambra tile, late 14th century, Malaga or Granada, Spain. Earthenware painted over and incised in an opaque white glaze. This tile was acquired from Alhambra in1791by a traveller to the site. The Nasrid rulers were responsible from 1232 for the construction of the Alhambra in Granada, one of the best-known examples of Islamic architecture in the world. / © The Trustees of the British Museum

Iznik basin, c. 1545-1550, Ottoman dynasty, Iznik, Turkey. Made of cobalt, green, turquoise painted and glazed stone paste. This magnificent bowl, which may have been used for ablutions by the sultan or his entourage, is decorated with lotuses, saz leaves, tulips and prunus stems amongst other flora, a style typical of Ottoman court art. It was made at Iznik the major centre of ceramic production during the Ottoman era. / © The Trustees of the British Museum

Iznik basin, c. 1545-1550, Ottoman dynasty, Iznik, Turkey. Made of cobalt, green, turquoise painted and glazed stone paste. This magnificent bowl, which may have been used for ablutions by the sultan or his entourage, is decorated with lotuses, saz leaves, tulips and prunus stems amongst other flora, a style typical of Ottoman court art. It was made at Iznik the major centre of ceramic production during the Ottoman era. / © The Trustees of the British Museum

The new gallery will accommodate a permanent presence for light-sensitive objects such as works on paper and textiles which will be regularly changed. These will include stunning 14th-century illustrated pages from one of the most celebrated oral traditions, the Persian epic Shahnama (Book of Kings) which will be shown alongside monumental folios of the 16th-century Indian Mughal emperor Akbar's Hamzanama (Adventures of Hamza). These belong to the Islamic literary tradition, which stems from a rich and diverse history of storytelling that pre-dates the advent of Islam, featuring epics about real and mythical kings and heroes, as well as romances and religious narratives.

Seated youth reading, c. 1625-26. Isfahan, Iran. Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper. While this figure's face and the vegetation surrounding him recall other works by Riza Abbasi, features such as the sitter's slender proportions, his seat, and an intriguing Persian inscription suggest that the painting may pay homage to Muhammadi, a 16th-century artist from Herat. The inscription also references the effaced royal seal below the figure's seat, suggesting the work may have been commissioned by the Safavid ruler, Shah Abbas I (r. 1588-1629). / © The Trustees of the British Museum

Seated youth reading, c. 1625-26. Isfahan, Iran. Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper. While this figure's face and the vegetation surrounding him recall other works by Riza Abbasi, features such as the sitter's slender proportions, his seat, and an intriguing Persian inscription suggest that the painting may pay homage to Muhammadi, a 16th-century artist from Herat. The inscription also references the effaced royal seal below the figure's seat, suggesting the work may have been commissioned by the Safavid ruler, Shah Abbas I (r. 1588-1629). / © The Trustees of the British Museum

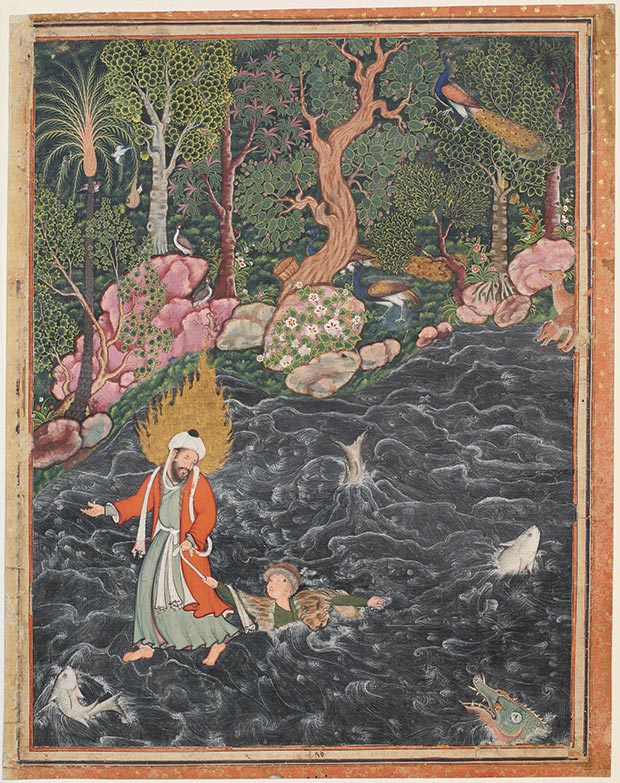

The Hamzanama, c.1558-73. India. Ink and opaque watercolour on cloth; text side: ink on paper. This page is from the Hamzanama (Adventures of Hamza), an epic romance inspired by the legendary adventures of Prophet Muhammad's uncle Amir Hamza. The Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1556-1605) enjoyed reciting and listening to tales from the Hamzanama so much that he commissioned an illustrated version in Persian, the language of the court. Taking fifteen years to complete, the final work encompassed 14 volumes with 1,400 paintings by Indian and Iranian artists, less than 150 of which survive today. / © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Hamzanama, c.1558-73. India. Ink and opaque watercolour on cloth; text side: ink on paper. This page is from the Hamzanama (Adventures of Hamza), an epic romance inspired by the legendary adventures of Prophet Muhammad's uncle Amir Hamza. The Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1556-1605) enjoyed reciting and listening to tales from the Hamzanama so much that he commissioned an illustrated version in Persian, the language of the court. Taking fifteen years to complete, the final work encompassed 14 volumes with 1,400 paintings by Indian and Iranian artists, less than 150 of which survive today. / © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Raven addresses an assembly of animals, c.1590. India. Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper; mounted on an album folio. This densely populated scene of a raven addressing a gathering of real and fantastic animals probably once belonged to an illustrated manuscript and is attributed to the Mughal court artist Miskin. / © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Raven addresses an assembly of animals, c.1590. India. Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper; mounted on an album folio. This densely populated scene of a raven addressing a gathering of real and fantastic animals probably once belonged to an illustrated manuscript and is attributed to the Mughal court artist Miskin. / © The Trustees of the British Museum

The arts of the book and calligraphy will be displayed alongside musical instruments, including an outstanding 19th-century lyre from Sudan and 20th-century shadow puppets from Turkey. Works on paper by artists from the Museum's growing collection of contemporary art will be presented in dialogue with the cultures of the past. An exciting collaboration with the Prince's School of Traditional Arts will also emphasise continuing traditions of paper-making, painting and illumination alongside masterpieces of Persian and Indian painting. An area dedicated to temporary displays will open with an exhibition from the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia exploring the idea of the arabesque; an abstract vegetal motif that spread across the Muslim world for over 1000 years.

Keris and sheath, 19th century, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Metal, wood, gold, ivory, diamonds, silk and silver-wrapped thread. This keris or ceremonial dagger was made by the Muslim Bugis people of south Sulawesi, Indonesia’s third largest island. The dagger's hilt (handle) and sheath (cover) indicate the specific region in which they were produced, and this high-status example has an ivory hilt and metal collar inlaid with diamonds. A blade-smith constructs blades using layers of iron ore and meteorite nickel which are folded dozens or hundreds of times, creating distinct damascened patterns called pamor. / © The Trustees of the British Museum

Keris and sheath, 19th century, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Metal, wood, gold, ivory, diamonds, silk and silver-wrapped thread. This keris or ceremonial dagger was made by the Muslim Bugis people of south Sulawesi, Indonesia’s third largest island. The dagger's hilt (handle) and sheath (cover) indicate the specific region in which they were produced, and this high-status example has an ivory hilt and metal collar inlaid with diamonds. A blade-smith constructs blades using layers of iron ore and meteorite nickel which are folded dozens or hundreds of times, creating distinct damascened patterns called pamor. / © The Trustees of the British Museum

The displays are enhanced by an engaging new programme of digital media that comprises a series of introductory films focusing on topics such as architectural decoration, ceramic technology, arts of the book and music. An accompanying website will allow for further research and exploration of the collections on display. The visitor will have the opportunity to engage directly with objects at a dedicated handling desk managed by the Museum's volunteer programme.

Designed by Stirling Prize-winning architects Stanton Williams and in close collaboration with the British Museum, the new gallery has been created by opening up and significantly refurbishing two historic, 19th-century spaces on the first floor of the Museum. Adjacent to recently renovated European galleries, these spaces have been closed to visitors for several years.

The curatorial team consists of Venetia Porter, Ladan Akbarnia, Fahmida Suleman, Zeina Klink-Hoppe, Amandine Marat and William Greenwood.

Hartwig Fisher, Director of the British Museum, said, "The galleries and permanent displays of the British Museum's collection show us the interconnectedness of our shared cultures. The Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World allows us to display this world-class collection to tell a more universal story of Islam in a global context. I am grateful to the Albukhary Foundation and the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia for supporting this important new gallery."

Venetia Porter, Assistant Keeper of Islamic and Contemporary Middle East at the British Museum, said, "This new gallery has given us the opportunity to completely re-visit our collection and to explore the history, complexity and diversity of the cultures of the Islamic world from West Africa to the Malay Archipelago."

Syed Mokhtar Albukhary, Chairman of the Albukhary Foundation, said, "I would like to thank the British Museum for a fruitful collaboration and for the opening of the Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World which aims at displaying the convergence and divergence of Islam. In the context of globalisation, I sincerely hope that this new galley will attract a multicultural audience, and contribute to understanding the history, arts and cultures of the Islamic World".

Syed Mohamad Albukhary, Director of the Islamic Art Museum Malaysia, said, "After years of preparation, it is enormously gratifying to see the Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World open to the public. This gallery will certainly form an educational space and will contribute to strengthening the visitor's experience and in their understanding of the Islamic civilisation".

Comments

Add a comment