An Interview with Riyadh-Based Artist Eiman Elgibreen Saudi Identity and Speaking Back

Jul 08, 2016 Interview

Anyone keeping a pulse on the global contemporary art market knows that Saudi art has become increasingly visible and sought after in recent years. Exhibitions, art catalogues and news articles have emerged in both East and West as Saudi artists are attaining record-breaking prices for their work. To find out more about the Saudi art scene and to discuss her work, I sat down with Eiman Elgibreen. The young Riyadh-based artist, in addition to making art, teaches art history and criticism at Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University. Eiman’s smart, timely art and uncanny grasp of cultural politics make her definitely an artist to watch, as does her almost overwhelming enthusiasm for art, ideas and her country. She is currently exhibiting work in the group show 'Identity' at the Made in…Art Gallery in Venice.

Well, to be honest, even we Saudi artists are still trying to figure out our art scene. Over the past ten years, a strong movement of change has occurred. There are many exciting initiatives like the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture and opportunities like Jeddah’s 21,39 art festival or Riyadh’s Art Days appearing every day and this keeps pushing the wheel of Saudi art towards new directions that we never anticipated. The sense of ambiguity, instability, and the diversity of styles seen in current Saudi art make it, at least for me, far more interesting than how it used to be prior to 2006, when it had a more defined identity.

Eiman Elgibreen, Three Girls. Clay, iron, and acrylic color. h.40 x w.26 x d.8 cm. Acquired by the Saudi Ministry of Culture and Information / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Three Girls. Clay, iron, and acrylic color. h.40 x w.26 x d.8 cm. Acquired by the Saudi Ministry of Culture and Information / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Treasures That Have Yet to Be Discovered. Clay and acrylic paint. 20x25 cm. Image: Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Treasures That Have Yet to Be Discovered. Clay and acrylic paint. 20x25 cm. Image: Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

I was born in 1981. I therefore grew up in the heyday of the oil wealth. I witnessed the incredible architectural projects of the country being built, and I was raised and educated by a new generation of Saudis who were proud of their contribution to this country. I also grew up hearing my grandmothers' proud stories about their heritage, and learned why many customs and traditions were invented and followed by people in the past. This subject was constantly brought up by old aunties and grandmothers as they were afraid that urbanization and the new materialism might distract us from our true values, that is being human and having cultural agency.

Then, when 9/11 happened, I realized for the first time in my life that the rest of the world sees us differently. It created an identity crisis for me, so I made a conscious act of remembering all the positive ideas and attitudes I heard and witnessed growing up, and tried to incorporate them and share them with others through my art.

Eiman Elgibreen, Do not Judge Me, Just Look at My Work.Mixed media on wood.A series of six panels. Overall size of each panel: (32x36) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Do not Judge Me, Just Look at My Work.Mixed media on wood.A series of six panels. Overall size of each panel: (32x36) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Do not Judge Me, Just Look at My Work.Mixed media on wood.A series of six panels. Overall size of each panel: (32x36) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Do not Judge Me, Just Look at My Work.Mixed media on wood.A series of six panels. Overall size of each panel: (32x36) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Do not Judge Me, Just Look at My Work.Mixed media on wood.A series of six panels. Overall size of each panel: (32x36) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Do not Judge Me, Just Look at My Work.Mixed media on wood.A series of six panels. Overall size of each panel: (32x36) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Do not Judge Me, Just Look at My Work.Mixed media on wood.A series of six panels. Overall size of each panel: (32x36) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Do not Judge Me, Just Look at My Work.Mixed media on wood.A series of six panels. Overall size of each panel: (32x36) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Do not Judge Me, Just Look at My Work.Mixed media on wood.A series of six panels. Overall size of each panel: (32x36) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Do not Judge Me, Just Look at My Work.Mixed media on wood.A series of six panels. Overall size of each panel: (32x36) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Do not Judge Me, Just Look at My Work.Mixed media on wood.A series of six panels. Overall size of each panel: (32x36) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Do not Judge Me, Just Look at My Work.Mixed media on wood.A series of six panels. Overall size of each panel: (32x36) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Yes, this is true. The series you are referring to started as a project about Saudi women's role in art and history. I kept seeing my sisters and I in these colourful, abstract murals here, knowing that it was a form of art made by young women of the southern region to announce the beginning of a new stage of life, proving to their community their capacity to take charge of their lives and express themselves. The three women you see in my painted sculptures made in my mid-twenties represent my younger sister, my twin sister, and me. At the time, we were all trying to find our places in the world, but we also each faced obstacles as any twenty something year old does.

Yes, by that time I had embraced the topic that I had been trying to avoid relating to how I was perceived as a Saudi Muslim woman, but not by the people of England. My awareness came from two sources: first, from the media and second, from a few Saudi-based curators who cancelled their offers to show my work abroad once they realized that I wore a headscarf. For them, this would not be good for business as it would perpetuate the stereotype of Saudis being extremists. They needed a Western model to prove that we are "civilized", unfortunately. It’s a kind of internalized colonialism.

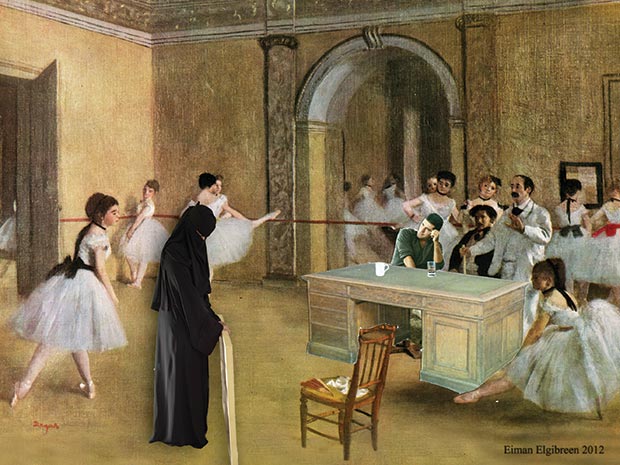

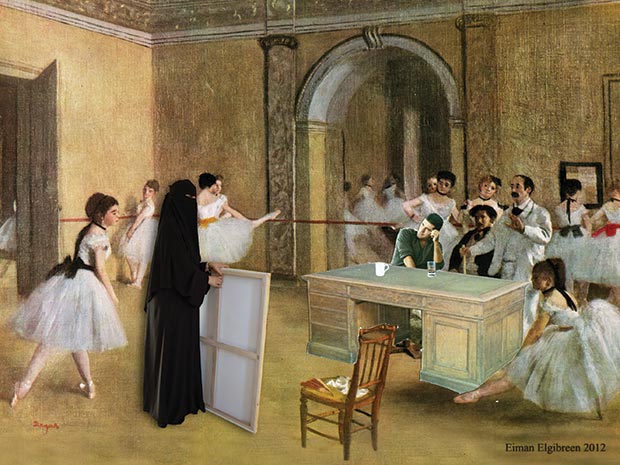

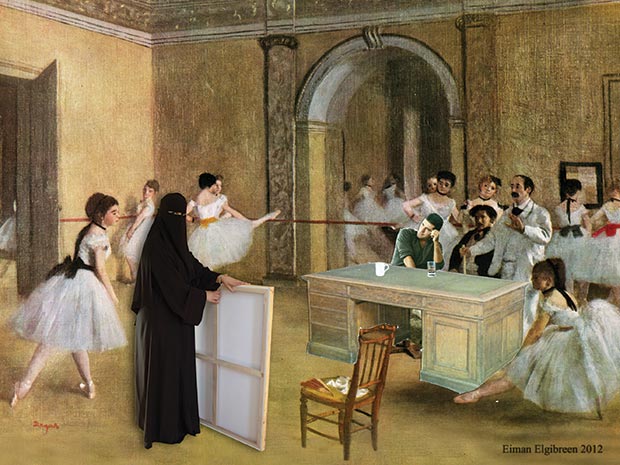

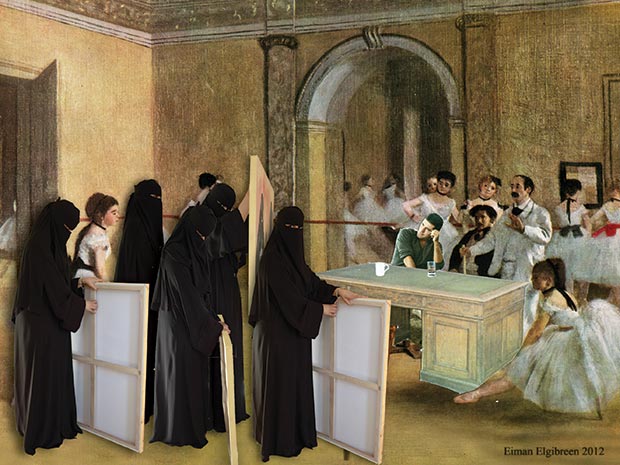

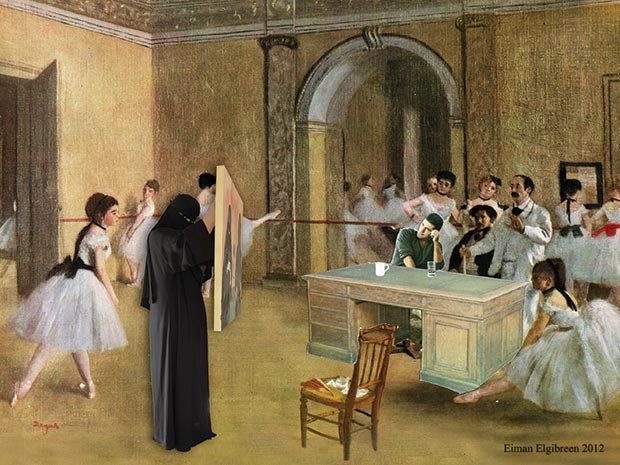

After a series of offer cancellations, I decided to use a more provocative symbol in my work than the simple headscarf, not just to express my anger, but also to allow for discussion by displaying contradictory attitudes with regard to facial veiling: niqab-wearing women, the norm in Riyadh, are deemed to need liberation and, yet, are not allowed to express themselves! Banksy’s photo montage of Dégas's Dance Studio (1872) in which he inserts Simon Cowell's picture shows the similarities in the ways talent was judged then and now, and the painting, highly appreciated by art lovers in both Saudi Arabia and England, seemed a good context in which to reference 'a fully-veiled artist'.

Of course, I never tried to approach any curator with this work as I thought they would never accept it! I decided instead to curate a show of Saudi female artists in London. I convinced the Saudi Cultural Bureau to fund it, and my friend Noof Al-Nassar convinced Brunel University to host the show. They gave us a building lobby for 48 hours only, but the response we received was incredible. A couple of months later, Ashraf Fyadh from Riyadh’s Athar Gallery, heard about 'Do not Judge Me, Just Look at my Work' and asked me to exhibit in the show 'Rhizoma' he was co-curating in Venice. From that point onward, I was back on track, receiving good reviews and subsequent offers, interestingly, because of 'Do not Judge Me' and the second piece I exhibited, 'Does a Face Make a Difference?'.

Eiman Elgibreen, Banksy and I. Photomontage prints mounted on Scandinavian Redwood. Overall size: 36 x 64 cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Banksy and I. Photomontage prints mounted on Scandinavian Redwood. Overall size: 36 x 64 cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Banksy and I. Photomontage prints mounted on Scandinavian Redwood. Overall size: 36 x 64 cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Banksy and I. Photomontage prints mounted on Scandinavian Redwood. Overall size: 36 x 64 cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

I think that art can help displace this gaze, but it has to be a reciprocal effort. One of my most enjoyable moments when I show my work is seeing people's reactions change after reading my statements. On many occasions, I have been pulled over by a sensitive person who tells me, with a tear in their eye, how badly they feel because Muslim women have to endure oppressive practices. However, their faces, more often than not, turn pale once I explain that this is actually not what I am trying to say. I’m pointing to everyone’s right to have cultural agency. However, I have to stress that I truly understand and even sympathize with how people feel about the Muslim world, as I too am exposed to the same media channels and their portrayals of Muslims and it certainly scares me. This is why I try to challenge people's perceptions and deconstruct stereotypes by merging contrasting symbols and styles.

Eiman Elgibreen, What Are You Looking at? Mixed media on wood. 32x36.cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, What Are You Looking at? Mixed media on wood. 32x36.cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

This work addresses the important question of whether people’s appearance affects the value of their accomplishments. To challenge the viewer’s perception, the sculpture is presented in a rather contemporary form: 64 cut and painted bricks placed on a large acrylic and mirror base. The black veils covering the female figures make it hard to escape the uncanny feeling which prevents us from seeing beyond the stereotype. But then the viewer discovers, by the reflection in the mirror base, that there is a smiling face of a young girl. The experience is jarring as it highlights that individuality is inherent and beyond the visual and also increases feelings of uncertainty about the reality of things around us. The images of the young girls used in this sculpture are those of accomplished, conservative Saudi women who wanted to object against being seen in any way that undermines their professional accomplishments just because they hold on to cultural traditions of dress.

In fact, 'Does a Face Make a Difference?' was originally inspired by a classical Arabic poem from the 8th century. It tells the tale of a man who fell in love with a beautiful woman who wears a black cloak. Before this poem, Muslim women used to wear cloaks of different colours. However, this poem became so popular that women, hoping to be like the woman described, began wearing black cloaks instead. So, I was also exploring how this poetic symbolic concept of beauty attached to the black cloak in old Arabic culture has changed and, more generally, how signs and symbols are sometimes difficult to translate across cultures.

Eiman Elgibreen, Does A Face Make a Difference? Mixed media on limestone bricks.Overall size: 60x200x100 cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Does A Face Make a Difference? Mixed media on limestone bricks.Overall size: 60x200x100 cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Does A Face Make a Difference? Mixed media on limestone bricks.Overall size: (w.60x l.200 x h.100) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Does A Face Make a Difference? Mixed media on limestone bricks.Overall size: (w.60x l.200 x h.100) cm. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

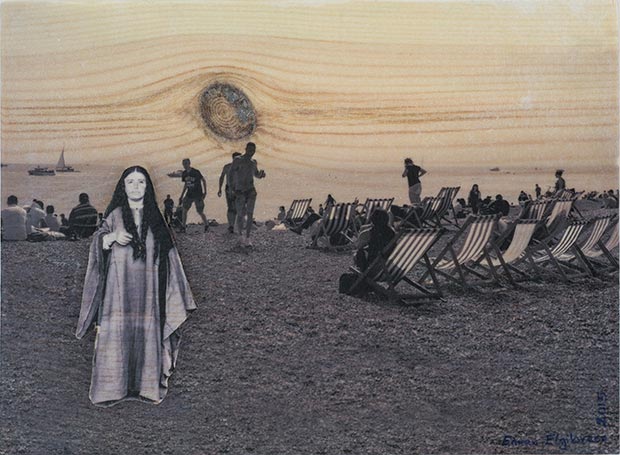

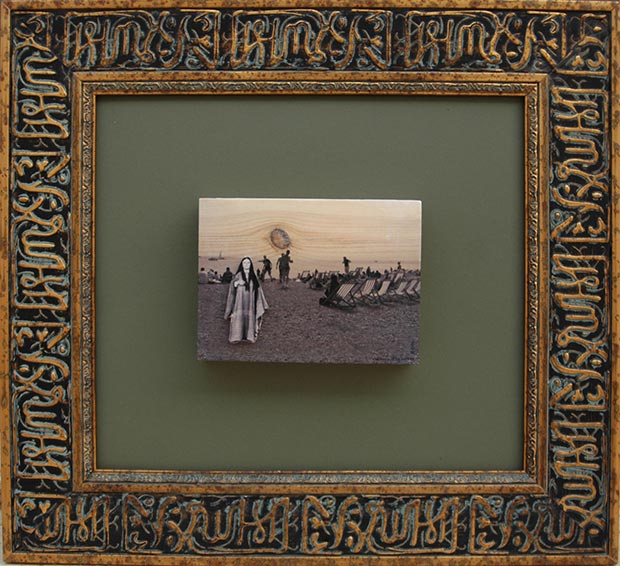

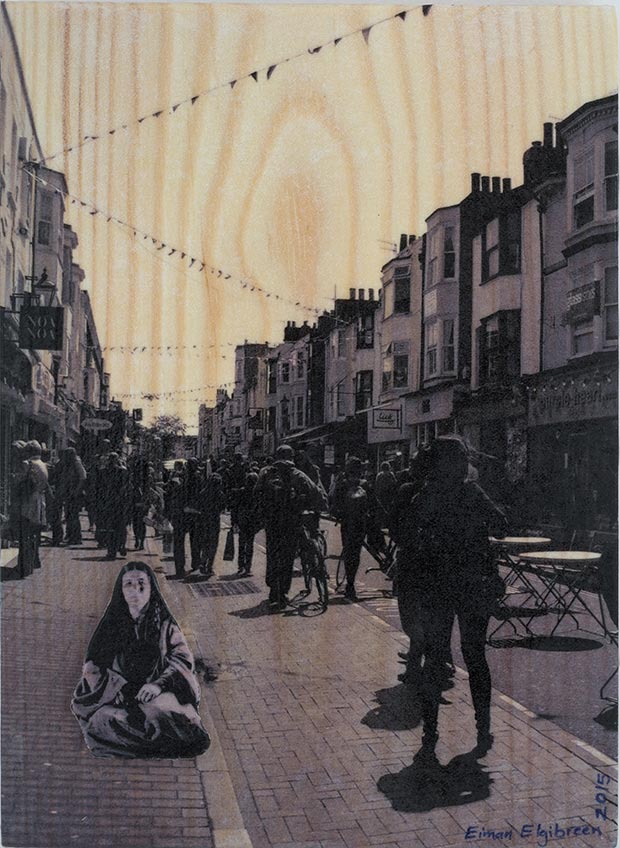

Yes, she is a source of comfort. I found Turkiyyeh’s image and her story written with it in the archive of Gertrude Bell at Newcastle University. She was the only identified woman from my region in the archive. The rest were anonymous. ‘Turkiyyeh’ was kidnapped as a young girl and sold in the slave market in Turkey, then moved from one house to another until she reached her final destination of Hail, Saudi Arabia, where she met Gertrude Bell. So I felt I knew her and I could not leave her alone.

The irony is that for years, Saudis have circulated her image on the internet mistaking her for another woman. Many have claimed that she was their grandmother, but no one ever bothered to research her real identity. I saw her image as a potent sign of the identity crisis and nostalgic feelings experienced by many Saudis, not just by me; she was therefore perfect to address key questions at the heart of my work, such as Who I am? Can I fit in to this hybrid world? Will I ever be accepted? Will I be misrepresented and overshadowed by rumours like Turkiyyeh?

Eiman Elgibreen, Turkiyyeh at the Seafront. Mixed media on wood panels. h.15 x w.20 cm. 2015. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Turkiyyeh at the Seafront. Mixed media on wood panels. h.15 x w.20 cm. 2015. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Turkiyyeh at the Seafront (framed). Mixed media on wood panels. h.15 x w.20 cm. 2015. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Turkiyyeh at the Seafront (framed). Mixed media on wood panels. h.15 x w.20 cm. 2015. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Turkiyyeh in the North Laines. Mixed media on wood panels. w.15 x h.20 cm. 2015. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Turkiyyeh in the North Laines. Mixed media on wood panels. w.15 x h.20 cm. 2015. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

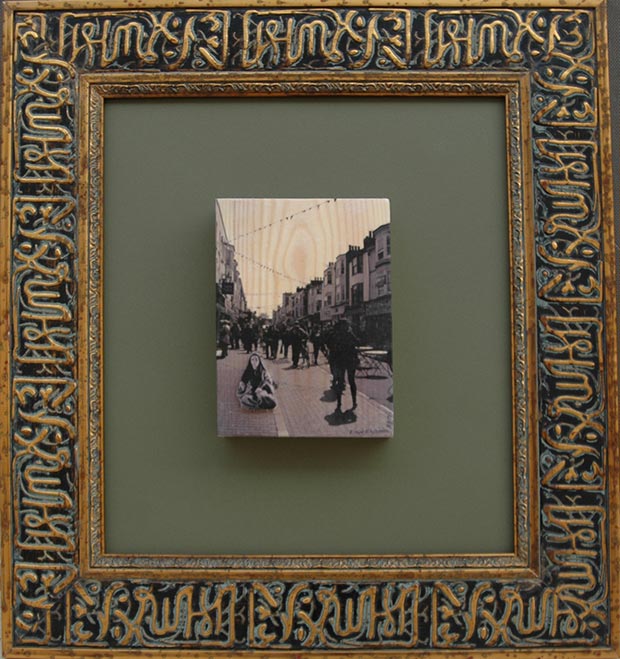

Eiman Elgibreen, Turkiyyeh in the North Laines (framed). Mixed media on wood panels. w.15 x h.20 cm. 2015. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Turkiyyeh in the North Laines (framed). Mixed media on wood panels. w.15 x h.20 cm. 2015. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

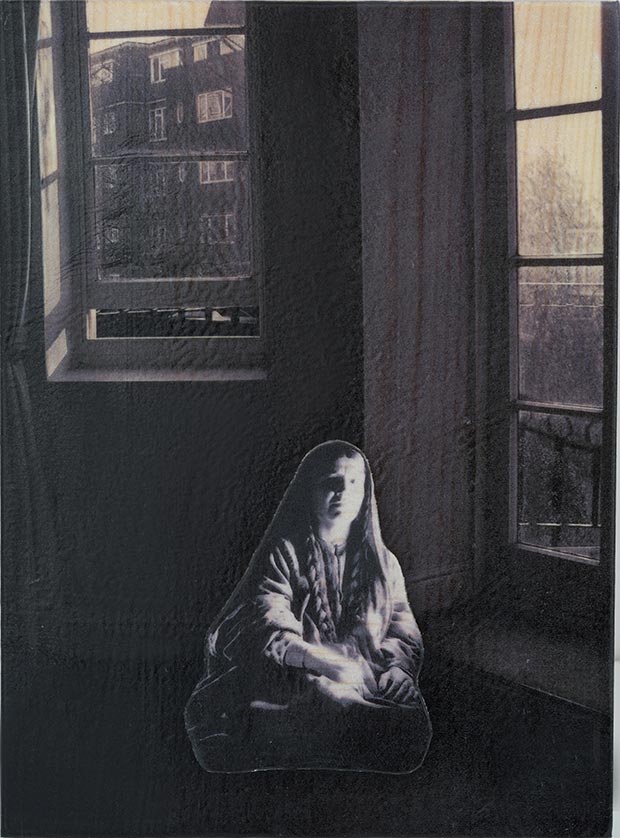

Eiman Elgibreen, Turkiyyeh at Home. Mixed media on wood panels. w.15 x h.20 cm. 2015. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Turkiyyeh at Home. Mixed media on wood panels. w.15 x h.20 cm. 2015. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

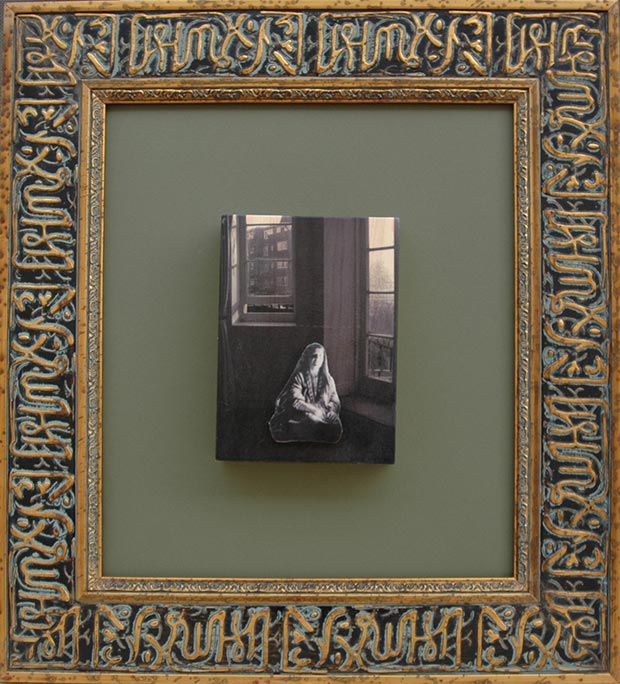

Eiman Elgibreen, Turkiyyeh at Home (framed). Mixed media on wood panels. w.15 x h.20 cm. 2015. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

Eiman Elgibreen, Turkiyyeh at Home (framed). Mixed media on wood panels. w.15 x h.20 cm. 2015. Private collection / Courtesy of the Artist

I have many projects simmering, but I am currently participating in a group exhibition called 'Identity' at the 'Made in… Art Gallery' in Venice from the 25th of June to the 15th of July.

Comments

Add a comment