The Next Generation: Contemporary Iranian Calligraphy

Jun 13, 2012 Exhibition

Although the artists have been trained in and inspired by classical calligraphy, tradition serves them mainly as a point of departure for their explorations of this art form. In an effort to document and recognize the importance of what is happening in contemporary Iranian art, the exhibition has gathered together work by young artists who represent this exciting period of transition.

'The Next Generation' showcases how these artists, working on both sides of Iran’s borders, deliver rare and unexpected insights into the artistic energy of a culture that is constantly evolving and adapting. Their use of calligraphy is significant: the practice was originally developed to transmit the word of God in written form. The idea was that the perfect word of Allah should be written down in a suitably perfect script. As a result, mastering the art often required years of rigorous training, and learning the various writing styles demanded strict adherence to established rules. Calligraphers, then, viewed themselves as artisans – not as artists. For them, an entirely original creation was not the highest aim; the highest aim was mastery within a long tradition.

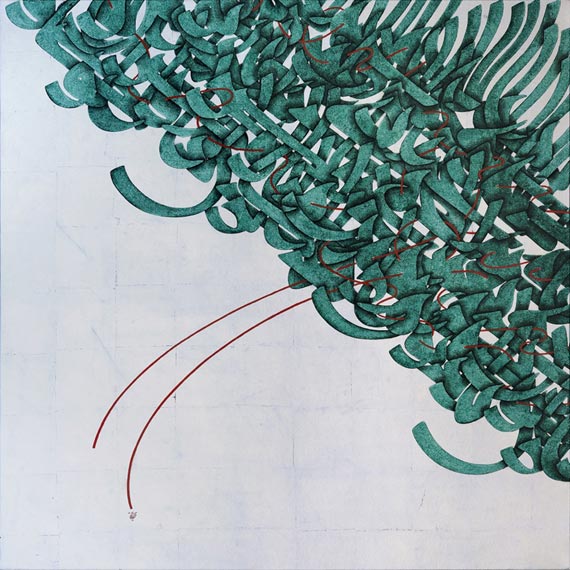

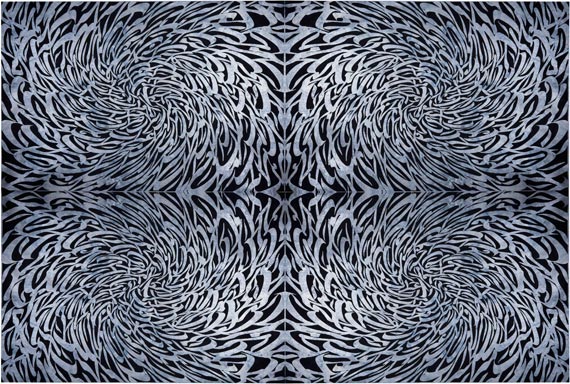

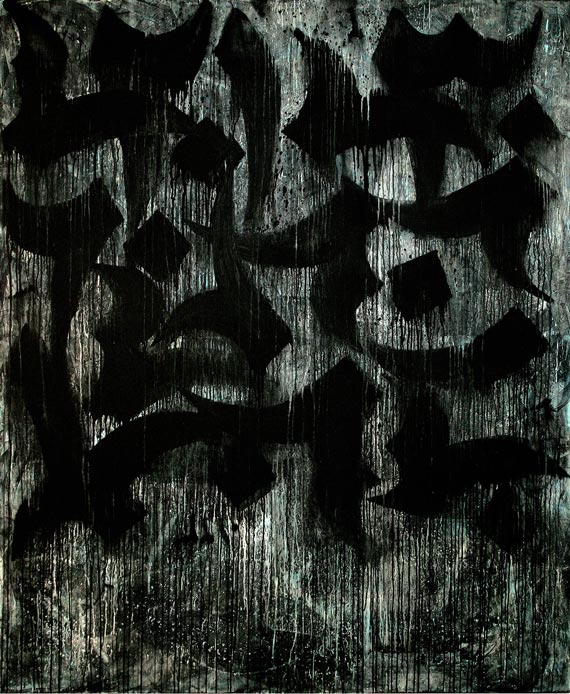

Image above: Aghighi Bakhshayeshi / Traces 8, 150x150cm, oil and silver leaf on canvas, 2012 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Aghighi Bakhshayeshi / Untitled, 150 x 150 cm, silver leaf and oil, 2012 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Aghighi Bakhshayeshi / Untitled, 150 x 150 cm, silver leaf and oil, 2012 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Aghighi Bakhshayeshi / Traces 8,150x150cm, oil and silver lea on canvas, 2012 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Aghighi Bakhshayeshi / Traces 8,150x150cm, oil and silver lea on canvas, 2012 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Tehran-based artist Aghighi Bakhshayeshi was trained in traditional calligraphy forms such as Nas’taliq and Muhaqqaq. Today, however, she incorporates Persian Kufi script into her work, creating symbolic art forms that reference both poetry and religion. Her artistic vision moves seamlessly across the boundary of traditional calligraphy into new modes of artistic creation. With a sensitive use of colour and rhythm and an academic precision, Bakhshayesh gives her work a unique, contemporary flavour.

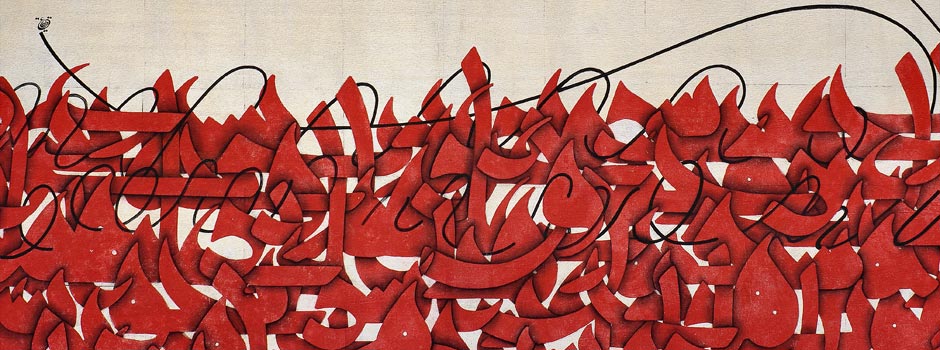

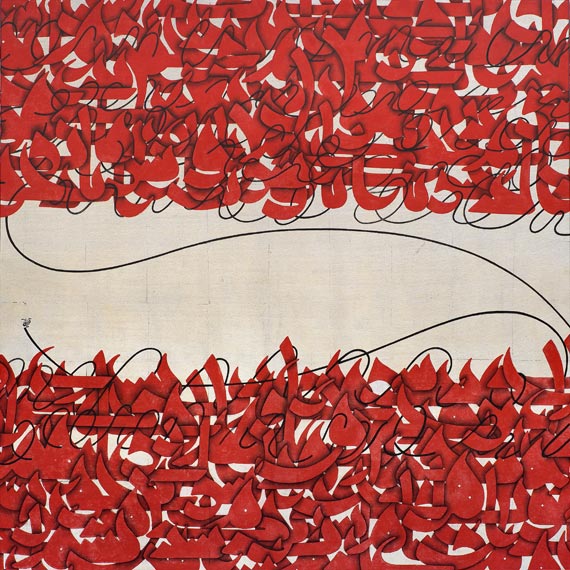

Mohamed Bozorgi / Cry 01, 224x330cm, mixed media on canvas, 2012 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Mohamed Bozorgi / Cry 01, 224x330cm, mixed media on canvas, 2012 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Tehran-based Mohamed Bozorgi practiced with the Society of Iranian calligraphers for 15 years and achieved the Excellent level. However, he stopped his training because he found the Society’s rules too restrictive, that they discouraged any formal innovation. In his practice, he uses the elegant harmonic movements of dancing curves to create beautiful repetitions. In recent years, he has used traditional calligraphic forms to navigate his own visual constructions, which has allowed him to create his own language in a contemporary format. Although the writing he has invented is rooted in Arabic and Persian, his main focus is exploring a more architectural approach. He develops geometric shapes as metaphors for dance and spiritual liberation, and he painstakingly writes by hand, refusing technological mediations.

Habib Farajabadi / Light, 180x150cm, acrylic on canvas, 2011 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Habib Farajabadi / Light, 180x150cm, acrylic on canvas, 2011 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Farajabadi heralds the dawn of a new generation of Middle Eastern abstraction. He is developing a unique personal vocabulary, finding inspiration in elements of postmodern western practices and merging them with Middle Eastern ones: in his work, De Kooning dances with calligraphy and Tehran graffiti mingles with Basquiat. A bohemian philosophy guides his practice, and he has found that borrowing styles and images from, for example, the Italian Arte Povera or the American Pattern and Decoration movement has been profoundly liberating.

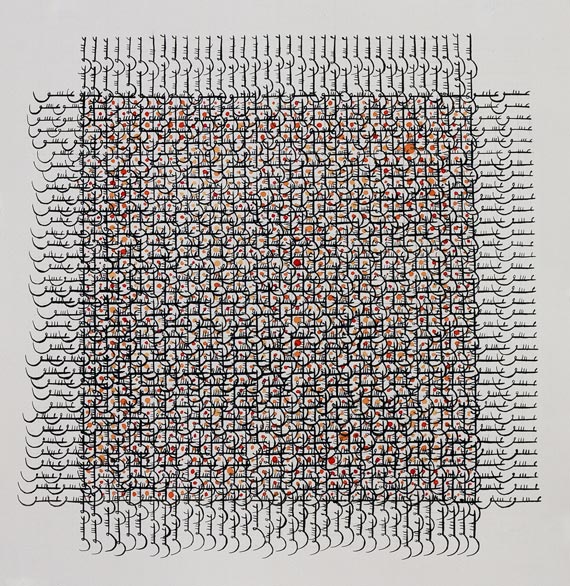

Hadieh Shafie / Fringe, 66x66cm, acrylic and ink on arches paper, 2011 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Hadieh Shafie / Fringe, 66x66cm, acrylic and ink on arches paper, 2011 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

In choosing to ignore the rules of calligraphy, Baltimore-based artist Hadieh Shafie creates works that foreground process, repetition, and time. To create her scroll pieces, Shafie marks thousands of strips of paper with handwritten and printed Farsi texts and then rolls them in concentric circles, concealing or revealing different elements of the texts. The concentric forms of both text and paper echo the dance of the whirling dervishes. In 2011, Shafie was short-listed for the Jameel prize, which is given by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, UK to artists who present traditional Islamic art and architecture in a contemporary way.

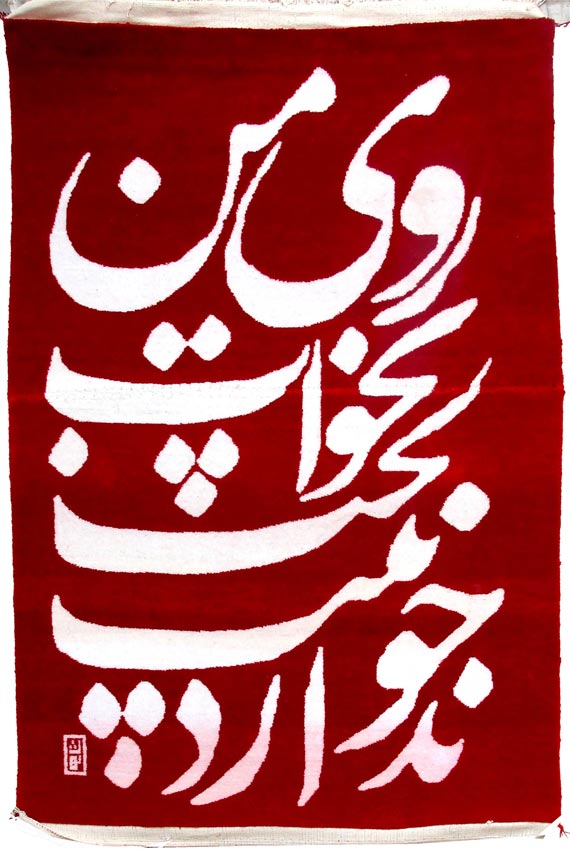

Abolfazi Shai / Don't sleep naked on me it is not good, 190x122cm, cotton and natural dye / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Abolfazi Shai / Don't sleep naked on me it is not good, 190x122cm, cotton and natural dye / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Though fully trained as a calligrapher, Abolfazi Shai has turned to creating carpets that make playful and ironic statements about Iranian culture. Literature, calligraphy, and carpet making have long been a vibrant part of Persian heritage, and while words are ever present in Persian culture – texts rendered in beautiful calligraphy adorn the mosques and public spaces – it is not common to find them on carpets, as it would be disrespectful for texts to be walked upon. Indeed, it is the intention of the artist for these carpets not to be walked on. Shai, however, uses these carpets as a showcase for texts from popular songs that the women weavers sing while working making a playful statement about popular songs and modern life.

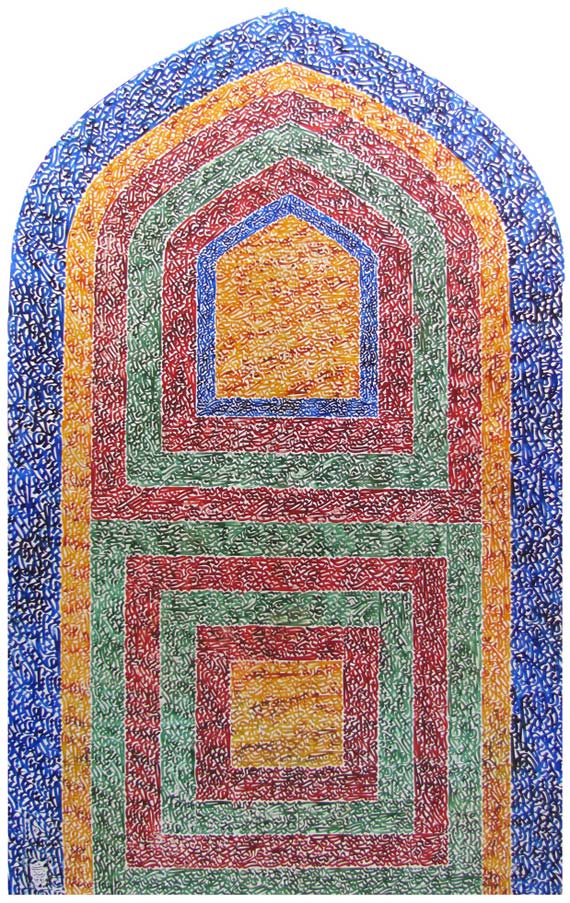

Behrouz Zindashti / Mihrab series 2, 230x140cm, ink on gold leaf, 2011 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Behrouz Zindashti / Mihrab series 2, 230x140cm, ink on gold leaf, 2011 / Courtesy of Galerie Kashya Hildebrand

Based in Tabrinz, Zindashti is influenced by an architectural principle that draws a correlation between architecture and ethics. He believes that his works function as alternative spaces for prayer, repeating the text of the Prayers for Prosperity in abstracted and improvisational Seljukain and Talisman scripts. His works express humbleness and spiritual devotion, but they also attempt to revive a forgotten art ethics, where repetitions of texts become prayers in their own right. Unlike traditional calligraphy that illustrates specific Koranic texts or poetry, Zindashti creates spiritual works with no direct references.

While the “next generation†of artists in this exhibition have received varying degrees of calligraphy training, their artistic journeys and their particular historical moment have inspired them to become artists, not artisans. Instead of following calligraphic traditions, these artists have followed in the footsteps of the early masters who first began to revolutionize the form, including Mohammed Ehsai, Charles Hossein Zenderoudi, and Nasrollah Afjehei, who were able to study in Iran as well as at art academies in Europe and could travel easily between east and west to pursue new inspirations while developing their own visual language.

Collectively, these selected artists’ practices push the boundaries of calligraphy, exploring it as a medium for expressing the self, originality, and the creative impulse. In consciously choosing to move into a fine art practice with their work, many of these artists have even abandoned the objective of rendering words in a readable form or in a specific calligraphic style; instead, their goal is to expand the expressive potential of the practice. To achieve their own free expression, they are breaking the rules; in doing so, they provide viewers with tangible, sensual experiences that invite them into various modes of expression that would otherwise be inaccessible.

Comments

Add a comment