Art Basel, Hong Kong (29-31 March, 2018) The Third Line at Art Basel Hong Kong

Apr 01, 2018 Art Event

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Decagon, 2009, Mirror and Plaster on Wood, Diameter of a 100cm circle / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Decagon, 2009, Mirror and Plaster on Wood, Diameter of a 100cm circle / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

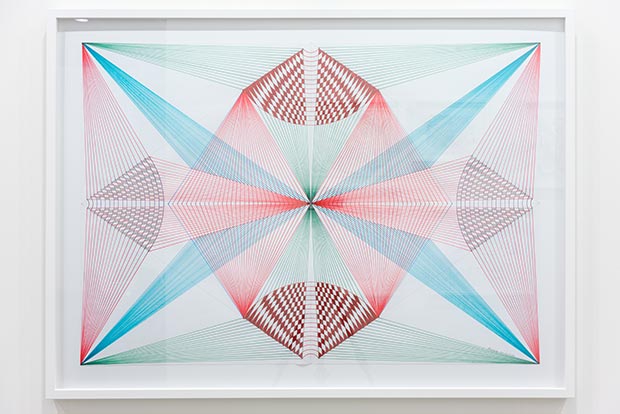

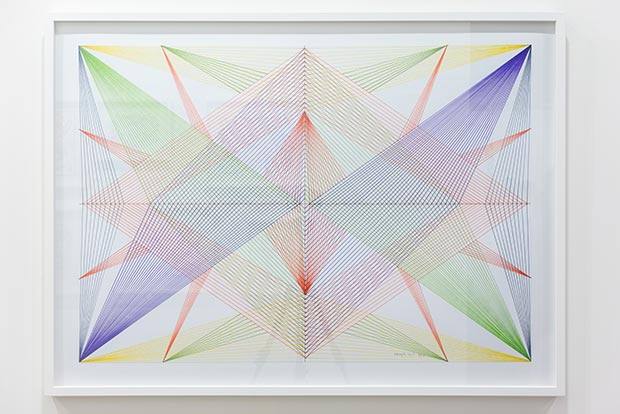

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian highlights the way the gallery’s artists both contemporise and revolutionise traditional regional crafts—in this case, reverse glass painting and the decorative technique of aineh kari which dates back to the 16th century. In its whorled central vortex, the multifaceted sculpture suggests Sufi cosmology’s meditations on time, space, and infinity even as it resembles the heart of a flower. It is joined by a rarely-seen series of colourful felt tip drawings from the 1990s, produced while the artist was living in New York, whose curvilinear, freewheeling squiggles suggest the rich tradition of Iranian carpet weaving even as they reveal a playful, whimsical side to an artist beloved for the immaculate precision of her geometric forms.

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Untitled 2, 2017, Felt tip marker and glitter on paper, 70 x 100 cm / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Untitled 2, 2017, Felt tip marker and glitter on paper, 70 x 100 cm / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Untitled 7, 2017, Felt tip marker and glitter on paper, 70 x 100 cm / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Untitled 7, 2017, Felt tip marker and glitter on paper, 70 x 100 cm / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Rana Begum similarly draws inspiration from the abstract clashes of form and colour found in urban environments with the repetitive geometry of Islamic art. The Folds grows from a series of experimental manipulations of paper that explored the materiality of drawing, which soon became works in their own right. Paper becomes sheets of copper and mild steel as the artist pulls this folded geometry into crisp, brightly-coloured three-dimensional forms that both challenge and expand relationships between colour, form and space. The wall-mounted sculptures are assertive yet retain the lightness and delicacy inherent in their inspiration. At the same time, their insistent physicality require the viewer to walk around them, which adds a visceral dimension to the experience.

Installation view, left Rana begum, right Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Installation view, left Rana begum, right Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Installation view / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Installation view / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

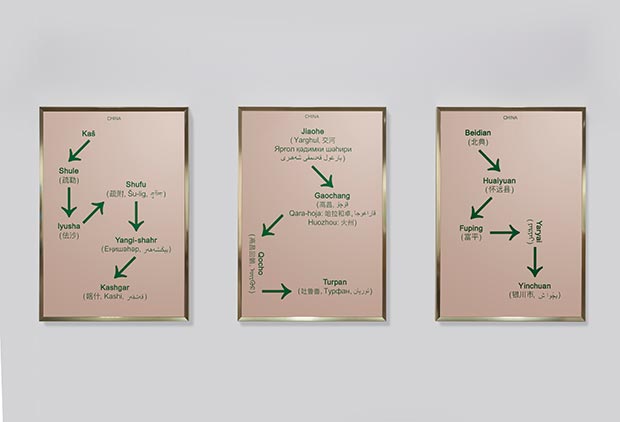

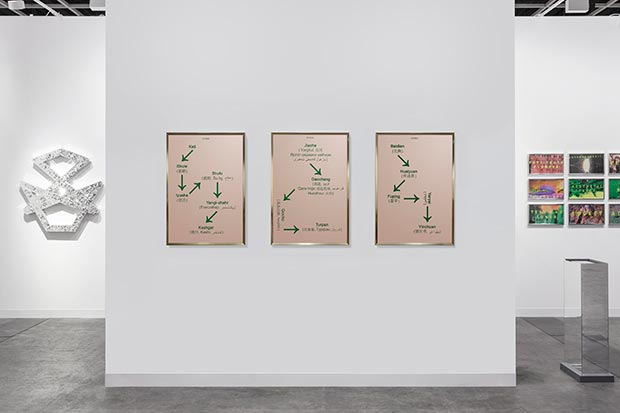

Slavs and Tatars ground themselves in a particular dialectical and geographic terrain, specifically the vast swathe east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China. Their series Love Me, Love Me Not considers these waves of power as they play out in the constantly changing names of 150 cities within their Eurasian remit. Like the eponymous game of unrequited love, each work plucks off the former names imposed on a city by its former colonisers to create a thorny record of an often brutal history. All three mirrors on view here feature ancient Silk Road cities with significant Muslim populations: Yinchuan, for example, is located in the Ninxiang Gui province, and is home to the Chinese Muslims known as Hui. Its mirror bears its former moniker of Yarvai, written in the vertical Mongol script. Another work features the former oasis stop of Kashgar; as one of China’s westernmost cities, it has variously been part of Turkic, Mongol, and Tibetean empires. A third mirror pays testament to another Xinjiang oasis city of Turpan, renowned for its grape production and a cave that is the holiest Muslim site in China. Given the difficulty of obtaining governmental permission to travel to Mecca, Turpan has become an important pilgrimage site.

Installation view, Slavs and Tatars / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Installation view, Slavs and Tatars / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Installation view, Slavs and Tatars / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Installation view, Slavs and Tatars / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Sometimes a piece of mirror catches the sun and blinds, as with the erasure of cultural and material histories that underwrites artist Sophia Al Maria’s practice. Best known for her coinage of Gulf Futurism, she considers how hypermediation, reactionary Islam, and the corrosive effects of consumerism result in the atomised isolation of individuals. In the short video Another Day Having Doubts (2015), Sophia transposes her interstitial experience growing up between two cultures to the peculiar condition of being not quite a digital native, but deeply precarious all the same. Crushed pills covers the screen in a nod to her generation’s preferred adaptive coping strategy, while on a nearby wall, digital prints from Everything Must Go, scream the exhortations of semiocapital.

Installation view / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Installation view / Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Comments

Add a comment