AN INTERVIEW WITH PAKISTANI ARTIST FATIMA ZAHRA HASSAN Thirst of the Soul

Aug 27, 2013 Interview

Fatima Zahra Hassan was one of the early graduates of the innovative miniature painting program established at the National College of Art in Lahore. Having mastered the age-old technique, Hassan set for herself the much more daunting task of infusing her work with the same perennial spirituality that emanates from the best of the Islamic miniature tradition. The artist explored the link between art and mysticism further while pursuing her Masters at the Royal College of Art and then Ph.D. at The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts in London. Currently a professor of fine art in the United Arab Emirates, Hassan continues to paint and show her work in Europe and the Middle East. She is presently participating in “Muslimaâ€, the global online show organized by the International Museum of Women.

Fatima Zahra Hassan / Courtesy of the Artist

Fatima Zahra Hassan / Courtesy of the Artist

Well, I am one of those who believe that teachers should definitely get due credit for their students’ achievements. I can single out Ustadh Bashir Ahmad in Lahore and Keith Critchlow and Paul Marchant in London. But it is not entirely the teaching. It is the traditional training of that very art form, which has stood the test of the time and is part of a living tradition. This particular program connects so well with Pakistan’s illustrious history that students can relate to it. As an early graduate, I probably suffered the most only because I decided to follow the path, which was less travelled at the time. The trend was then to paint something that was popular and called contemporary art and apparently had more followers.

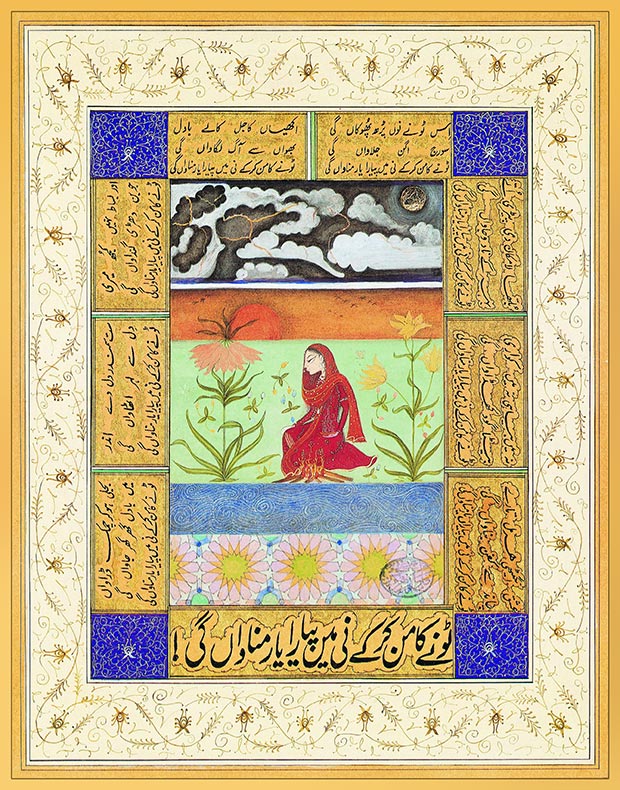

Love Charms (part of Album based on the poetry of Bulleh Shah), Water colour gouache, natural pigments, gold leaf on tea stained ‘Wasli’ paper, 1996/97, 8x12 inches / Courtesy of the Artist

Love Charms (part of Album based on the poetry of Bulleh Shah), Water colour gouache, natural pigments, gold leaf on tea stained ‘Wasli’ paper, 1996/97, 8x12 inches / Courtesy of the Artist

Artists like me who believed in the sanctity of traditional art were far less in number. I strongly believe that modernity grows from tradition and without tradition there is no modernity… there are millions of artists who are breaking away from tradition but people like us keep it alive, otherwise it will all be dead one day and there would not be anything left for posterity. It is also difficult to practice within a discipline and strict regime and follow certain parameters. Whereas it is easier to break away! One needs more time, passion, and skill to produce traditional work as opposed to something that needs manufacturing.

A Fall, Watercolour gouache, natural pigments on patterned and printed ‘Wasli’ paper, 2011/12, 15x25 cm / Courtesy of the Artist

A Fall, Watercolour gouache, natural pigments on patterned and printed ‘Wasli’ paper, 2011/12, 15x25 cm / Courtesy of the Artist

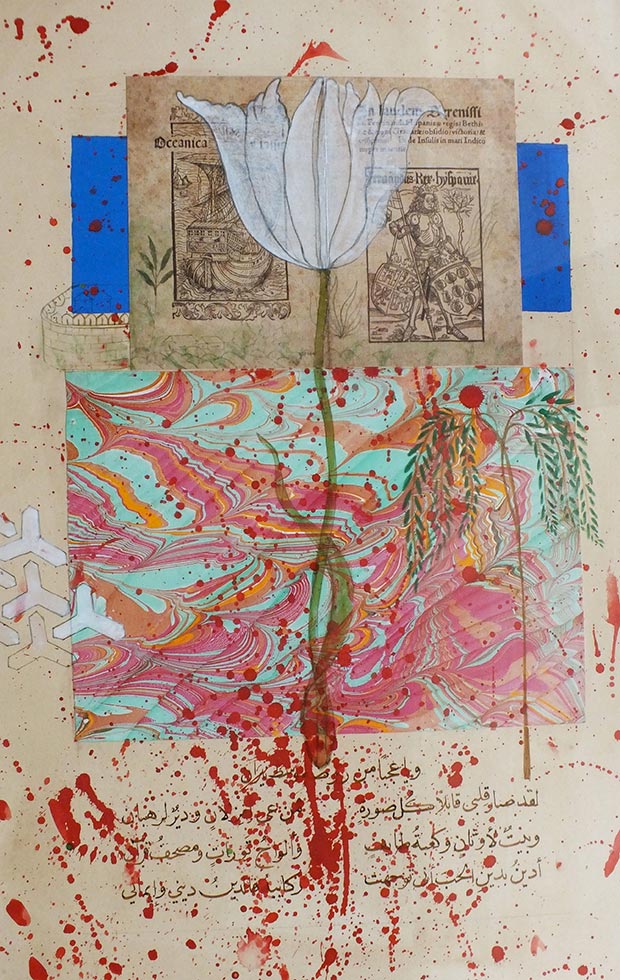

I Follow the Religion of Love, Watercolour gouache on printed tea stained ‘Wasli’ paper, 2012/13, 32x50 cm / Courtesy of the Artist

I Follow the Religion of Love, Watercolour gouache on printed tea stained ‘Wasli’ paper, 2012/13, 32x50 cm / Courtesy of the Artist

The book or kitab has had a pivotal role in Islam and Muslim history in imparting knowledge; therefore the arts of book or paintings done in order to convey what the text had to say became very popular in the Muslim world under various patrons. I grew up in a household where I was surrounded by books. My parents were keen on books, specially my father who had his own library that housed thousands of books and who was and still is an avid reader of history and theology. I grew up reading the poetry and literature of famous Muslim scholars. My maternal grandmother was also instrumental in introducing me to many leading poets and writers as she herself was a poetess and composed poetry in Persian and Urdu. At the age of twelve, I was already exposed to Sa’adi, Rumi, Attar, the Shahnameh, Firdawsi, Jami, Ghalib, Iqbal and many more…

I was keen on classical and Sufi music and was also interested in Qawwali which led me to the poetry of Bulleh Shah. I realized that politics, gender and socio-economic issues become irrelevant when one is a believer and has a spiritual connection with the Divine. For me, as a traditionalist, I have always felt the need to incorporate text in my work, using both image and words to convey the message of Divine Love.

I Am A Flower, Photograph on archival paper and watercolour gouache, 2009/10, 20x30 cm / Courtesy of the Artist

I Am A Flower, Photograph on archival paper and watercolour gouache, 2009/10, 20x30 cm / Courtesy of the Artist

A majority of contemporary artists chose to appropriate or decided to address issues pertaining to their circumstances or needs, I would say. I realized that I had to continue what I was taught and how I was taught. I was not trained to please galleries or collectors and buyers but to please my consciousness and paint on the ethos I believed in. My training in London harnessed the concept of sacred art and taught me a great deal about perennial philosophy, which is a cardinal element in sacred and traditional art. The Islamic Visual Arts’ program advocates “Art for Purpose†and not “Art for Art’s Sakeâ€. Art should have utility and be functional which makes it more like design. However, its’ principal elements are: Truth, Beauty and Goodness. We have to question ourselves, when we look at some artwork, whether or not this art is truthful or whether it has beauty - which is sense datum – and, above all, whether it really emanates goodness.

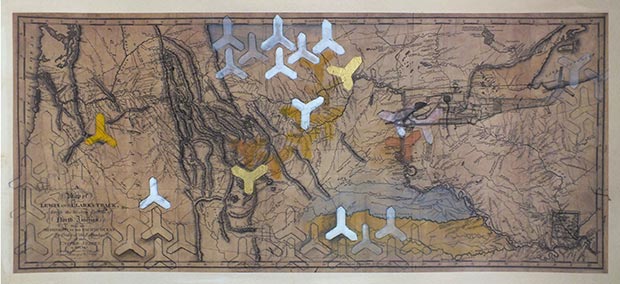

The Drones, Watercolour gouache, gold leaf on printed tea stained ‘Wasli’ paper, 2012/13, 25x8 cm / Courtesy of the Artist

The Drones, Watercolour gouache, gold leaf on printed tea stained ‘Wasli’ paper, 2012/13, 25x8 cm / Courtesy of the Artist

I personally feel that my work is both. My training in traditional South Asian and Middle Eastern manuscript illustration and then further grounding in ornament design including geometric and floral design has trained me to use symbols and allegories and create paintings that have stories to tell, for example the piece “Hide No More†named after the poem which inspired it and concludes with:

But I have fastened you in my heart. Now whither can you flee? O, the spouse of Bullah, I was your slave. And was dying for the sight of your sweet face. Ever and always I made hundreds of entreaties. Now sit securely in the cage of my body.

The poem’s language is so simple but has so much depth. As with all mystical poetry, there is a kind of double meaning. The subject is how elusive the Beloved is and how fast and fleeting the vision of Reality is. There is a perpetual game of hide and seek and the lover, again female, must constantly be on the watch so as not to lose sight of the Beloved, even though the Beloved tries to hide. The one who is constant and persevering and makes "hundreds of entreaties" will eventually capture the Beloved and fasten Him in his or her heart, so that finally He will "sit securely in the cage of my body."

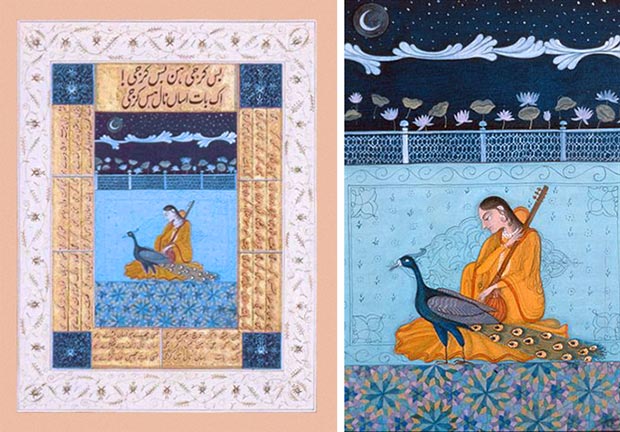

My painting shows a peacock and woman sitting against a pale sea-green background painted as a carpet, a crescent moon in the night-sky behind with stars like a jali screen with lotus flowers and leaves in between. The overall hues are different shades of blue and green. Green, as your readers know, is considered a mystical color in Islam associated with Paradise and the Prophet and blue is the color of the Heavens. I use these two colors most as they seem more than the others to indicate the infinite mystery of the Divine. The female figure is wearing yellow, which represents spring, new life and joy but it is also the color of longing and waiting for the Beloved. And while the peacock represents many different ideas in different traditions, one of its meanings in the Indo-Pakistani tradition, is that it stands for the male Beloved.

Hide no More (part of Album based on the poetry of Bulleh Shah), Watercolour gouache, natural pigments, gold leaf on tea stained ‘Wasli’ paper, 1996/97, 8x12 inches / Courtesy of the Artist

Hide no More (part of Album based on the poetry of Bulleh Shah), Watercolour gouache, natural pigments, gold leaf on tea stained ‘Wasli’ paper, 1996/97, 8x12 inches / Courtesy of the Artist

In traditional society and in particular with reference to Islamic or Muslim society, all is connected. One’s profession, daily life and spirituality are all interconnected. It means that all your work as a visual artist is a spiritual process and has an alchemy, which transforms you into a soul that is contented, known as the “Nafs Al-Mutmainnahâ€.

We have seen how the world changed after 9/11 and while it has done so much harm to Muslims as a whole, it has also done some good to Muslim culture. The world suddenly became interested in Islam and its culture and civilization. The world wanted to see the art, which was produced by artists living in Muslim countries. Curators, collectors, galleries and museum directors were all traveling to these countries to discover the art but the artists with Muslim identity, who were already living in the West, were in a different situation. The ones who submitted fully and were not resilient, they gained and the ones who kept the tradition alive were not necessarily getting any favors. The West generally wants to see art from the Islamic world that shows the negative side and all the lows rather than give an opportunity to everyone including those who are working on interfaith subjects, such as peace, benevolence, harmony and the love for humanity. The West is keener to see burka-clad women, women in niqab, and women who are deprived. I have yet to see interest in art from the Muslim world, which shows the positive side. In my case, I do not work with any gallery or agent but rather through a network, which helps me to see and undertake commissions.

Rumi, The Seeker, Watercolour gouache, natural pigments, gold leaf on tea stained ‘Wasli’ paper / Courtesy of the Artist

Rumi, The Seeker, Watercolour gouache, natural pigments, gold leaf on tea stained ‘Wasli’ paper / Courtesy of the Artist

As I mentioned earlier, beauty is a sense datum. Its’ importance is repeatedly stated in the Qur’an and the Hadith such as, "Verily, Allah is beautiful and loves beauty" and "God has inscribed beauty upon all things". Beauty is an abstract reality that needs shape and form for its manifestation. The process of its’ intentional and purposeful manifestation through form, colour, pattern and shape is what I call Art.

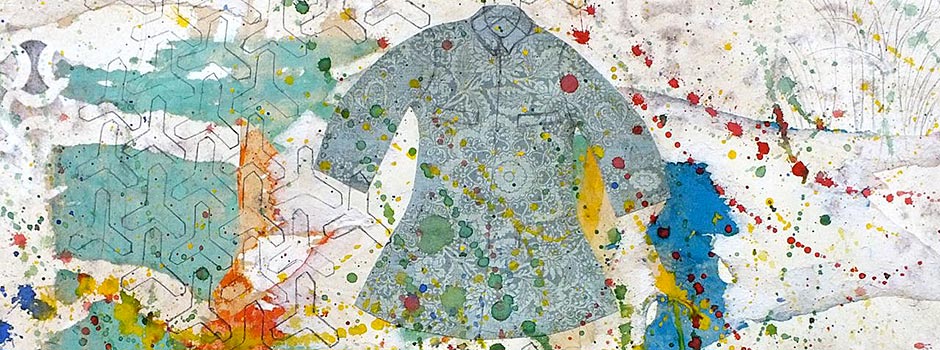

The Green Coat (Coat of Khidr), Watercolour gouache, natural pigments on ‘Wasli’ paper, 2012/13, 20x16 cm / Courtesy of the Artist

The Green Coat (Coat of Khidr), Watercolour gouache, natural pigments on ‘Wasli’ paper, 2012/13, 20x16 cm / Courtesy of the Artist

I am currently working on a series of paintings based on various topics such as construc-tion and building and how the South Asian labor force has played such an important role in building the modern UAE. I have taken an inspiration from an old 15th century Bihzad miniature in which he has painted a scene of the city of Herat’s construction.

Another series is based on “Objects of Desire†from the 60s and 70s such as the Vespa Scooter, typewriters, Raleigh bicycles, the Singer sewing machine and so on. The idea is to show these objects well drawn and painted to a 21st century audience. These were every one’s dream objects as opposed to today’s gadgets. I was born in the late sixties and I grew up with these objects myself, which were very beautiful. Being a British Pakistani, I strongly feel connected to these objects. For my kids, however, they have no meaning.

I am also working on old maps of the world, in particular US maps, and trying to transform and insert one Islamic pattern using a part of it to symbolize a drone. I never take a direct approach; rather, I use symbols, allegory and metaphor. I believe in painting that needs to be unfolded. I like mystery and most of my works have a maze or a labyrinth like structure, which is complex. Traditional miniature paintings or paintings from manuscripts always had mystery and, to this day, when you view a painting you will keep on unfolding it. The more you look at it, the more you discover.

I have two solo exhibitions and one group show coming up and am trying to paint different subjects from what I have painted before. In addition, I write and have many writing projects on the go and so life is very busy.

Night Of Union (part of Album based on the poetry of Bulleh Shah), Watercolour gouache, natural pigments, gold leaf on tea stained ‘Wasli’ paper, 1996/97, 8x12 inches / Courtesy of the Artist

Night Of Union (part of Album based on the poetry of Bulleh Shah), Watercolour gouache, natural pigments, gold leaf on tea stained ‘Wasli’ paper, 1996/97, 8x12 inches / Courtesy of the Artist

I really want to thank you and the IAM team for giving this opportunity to speak about my humble contribution to the arts of the Muslim World. I shall surely keep IAM posted with my projects, Insha Allah!

Comments

Add a comment