AN INTERVIEW WITH TURKISH CERAMIC ARTIST Tradition as Innovation in the Fine Art Ceramics of Zehra Çobanlı

Sep 25, 2017 Interview

Dr. Zehra Çobanlı is a major figure in the field of contemporary ceramics in Turkey. Her installations, structured around the notion of the multiple, bridge past and present and challenge the modernist view of their mutual exclusivity. They engage in a novel form of storytelling that probes not only Turkey’s Ottoman heritage and Anatolian culture, but also current critical issues like gender, migration and war. Çobanlı’s expertise in ceramic technology and history also informs her work and contributes to its unique depth and appeal. A graduate of Marmara University, Dr. Çobanlı helped to establish the Department of Ceramics atthe Faculty of Fine Arts of Anadolu University in Eskishehir, Turkey. She served for many years as the departmental head (1989-2007) and, later, as faculty dean (2007-2012)The master ceramic artist has exhibited in many countries, among them Turkey, Finland, Australia, Japan, Italy, China and the United States.

Dr. Zehra Çobanlı / Photo courtesy of the artist

Dr. Zehra Çobanlı / Photo courtesy of the artist

I have always thought that to reach the universal, one needs to consider the traditional and the local. I believe that in order to be universal, it is necessary to carry traces of our local and traditional cultural symbols from the land we live in. I think these offer up an opportunity to capture our originality by transferring our distinctive features to our art. The idea of reaching authenticity with the tips, symbols and messages I want to give, but without either leaving or just copying tradition, is the method that I use up to this day.

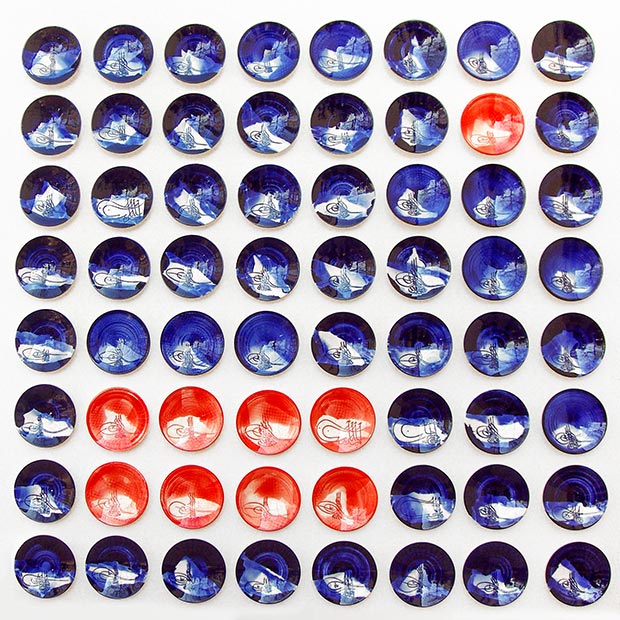

I started this series 'Mystery of Blue: Tughras' with a lot of excitement. During the Ottoman Empire, especially in the 14th and 15th centuries, the most beautiful Iznik ceramics of blue and white Iznik were made. The uniqueness of the blue in my ceramic plates recalls the eternity of the azure sky, the vastness of the seas and, at the same time, the abstract beauty of turquoise associated with a thousand senses. Some critics have said that the colour unifies the beauty of the installation.

I began the work by first examining the Ottoman sultans' signatures and the period in which the sultans lived. Sometimes, I put the sultan’s portrait and small details on the surfaces of the plates. 'Tuğra' comes from the Oğuz Turkish word 'tuğrağ', meaning the signature and order of the 'Hakan' or ruler. It has the same meaning as the Arabic word 'tevki' meaning symbol or signature. The tughra seal simply indicates that a document belongs to a sultan and represents the state. It is also, of course, linked to the art of calligraphy, that charming, independent artistic domain in which the East took shelter and breath. Islamic calligraphy has taken the responsibility of a kind of painting that expresses and describes human emotions such as dignity, immensity, courtesy, purity, loneliness and modesty.

I employed the whole form of the tughra in my plates. Nevertheless, I did not merely copy a specific sample of tughras, but utilized all the sultans’ tughras simultaneously. This work wants to recall and teach our society, often unaware of its culture, the long-lived and great state and art of the Ottoman Empire that emerged from the beyliks and lasted over six hundred years.

'Mystery of Blue: Tugras' installation, earthenware, underglaze blue slip and underglaze pigment, cobalt oxide,175x175 cm, 2005 / Courtesy of the artist

'Mystery of Blue: Tugras' installation, earthenware, underglaze blue slip and underglaze pigment, cobalt oxide,175x175 cm, 2005 / Courtesy of the artist

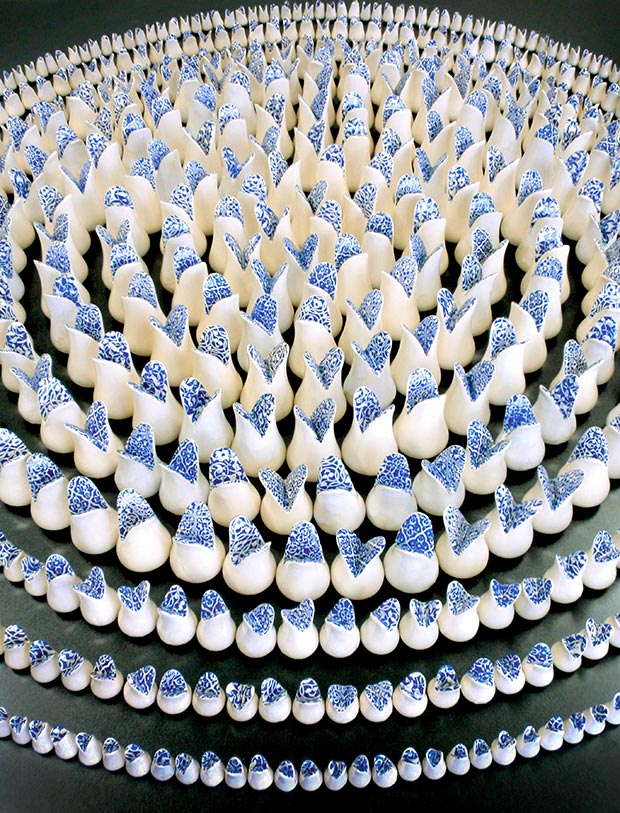

I love nature and flowers. Tulips are my favourite flower. The tulip or ‘laleh’ is said to be elegant, noble and a symbol of love. The tulip reveals the purity of colour and form. If we look at tulips, we can observe that they have opened their hearts to us. In Sufism, the flower symbolizes the Creator because 'Allah' is written with the same letters of alif, lam and ha. These letters are equivalent to the number 66 in abjad numerology used in the Ottoman period. These three letters are also found in the word ‘hilal’ or ‘crescent moon’ that was the emblem of the Ottoman State. For this reason, Turks believe that there exists a spiritual bond between the three words.

Artistic composition occurs through the use of many elements and principles together. Repetition reinforces the sense that an item is used exactly as it is. It also provides meaning. Rumi says "Let's be united, make it easy." 'Tulip Time' wants to convey the meaning of being together, of loving one another and of creating and sharing.

'Tulips time', stoneware, paper stencil, electrical kiln,4x4 meters, 2013 / Courtesy of the artist

'Tulips time', stoneware, paper stencil, electrical kiln,4x4 meters, 2013 / Courtesy of the artist

'Tulips time', stoneware, 2013 / Courtesy of the artist

'Tulips time', stoneware, 2013 / Courtesy of the artist

We were actually immersed in the Bauhaus school and this kept us away from traditional understandings of art. We were facing west. My turning point came when I was a researcher at the Tokyo Fine Arts and Music University in 1992. The influence of the late master of celadon, Professor Mihura Koheiji, was especially great. Japan, while very modern, remains connected to its cultural past. This experience pushed me to reexamine Anatolia and find a new way to observe and research popular idioms and local folk arts.

Ceramic installations in our country were not common in 1990s. I did my first installation work at that time to commemorate the soldiers who lost their lives in the disintegration of Yugoslavia. I used 21 types of different colours of clay-earth, representing the villages and towns where the soldiers came to war, and, because of this reason, I made monumental, geometric forms to represent the soldiers who I assumed were about 21 years old. What I feel is what I do: I do what is supposed to be for me, rather than think about what others would say or think.

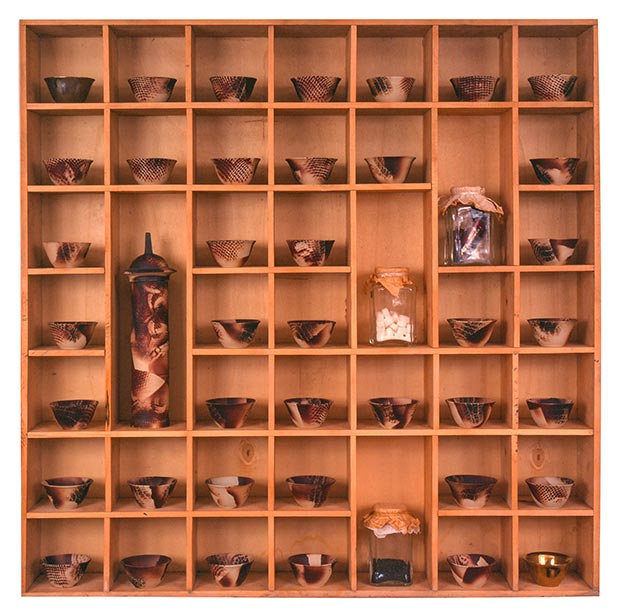

It is known that in the mythology of the Turks from Central Asia and the Middle East, the number 40 is considered a sacred number. This is true also in Islamic culture. In Anatolia, for example, the Qur'an is read 40 days after a death, after a birth and again on the newborn’s 40th day. The number 40 is fertile, ready and complete. It is the product of 4 which points to time and 10 which signifies information. It is very important in terms of spiritual maturity as well. Muhammad became a prophet at the age of 40 and there were 40 men, 40 women and 40 animals on Noah's ship. After celebrating my 40th birthday, both my maturity and the mystic depth of four decades led me to explore the widely-used Anatolian idioms around the number in my art.

'Birfincankahvenin 40 yılhatırıvardır' (One Cup of Coffee Cements 40 Years of Friendship), stoneware, brown slip, gold, 120x120 cm, 1998 / Courtesy of the artist

'Birfincankahvenin 40 yılhatırıvardır' (One Cup of Coffee Cements 40 Years of Friendship), stoneware, brown slip, gold, 120x120 cm, 1998 / Courtesy of the artist

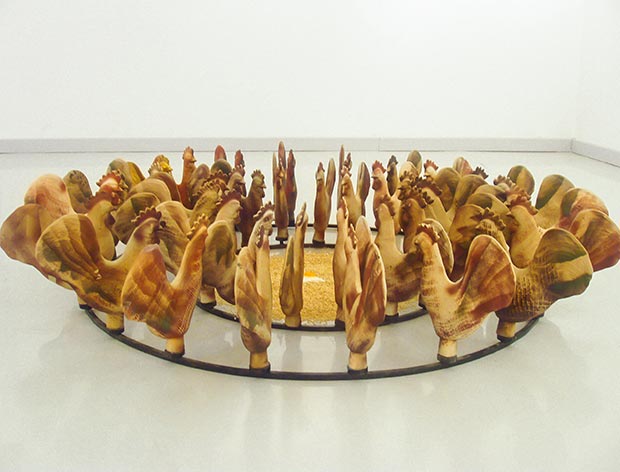

Bir gun horoz olmak 40 gun tavuk olmaktan yegdir, 1998/ Courtesy of the artist

Bir gun horoz olmak 40 gun tavuk olmaktan yegdir, 1998/ Courtesy of the artist

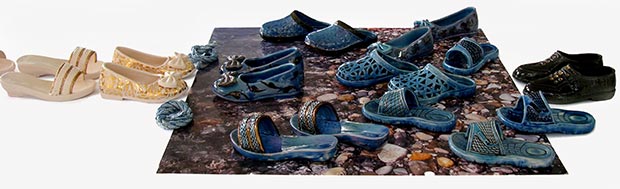

Yes, my works engage in storytelling, especially female storytelling. Although we talk about equality between men and women in Turkey, we are also very sad about not being always able to escape from situations that affect us deeply. For this reason, I cannot give up working in Anatolia to improve women's lives, cultures and rights. Some of my work addresses the female life that we have established in largely male-female social relations in daily life. This explains the references in my work to everyday reality and the bonds of friendship. The shoe is also a recurrent motif drawn from life. Used in repetition, it can indicate social status, social interactions, the difference of power between men and women, or, still yet, painful moments at sea and the plight of displaced children. Sometimes, I am against consumer society now, after all the horror stories of immigration.

'Child Alyan and Others', earthenware, turquoise glaze, china paint, gold, tile, 10x120x60 cm, 2015 / Courtesy of the artist

'Child Alyan and Others', earthenware, turquoise glaze, china paint, gold, tile, 10x120x60 cm, 2015 / Courtesy of the artist

Tebdili huyda vayda vardır, 2006 / Courtesy of the artist

Tebdili huyda vayda vardır, 2006 / Courtesy of the artist

I'm not a feminist. I defend the equality of men and women. For this reason, I spent a lot of my life working, asking permission from no one. I mean to be a good example for young women, adult women and women colleagues, as a mother, wife and female artist, educator and administrator. I believe in women's strength and ability. You discover yourself through the work you do. I mean there's nothing you cannot do. I think that this idea is reinforced in my art produced in a country whose ceramic culture extends for thousands of years.

_earthenware-coloured_brown_slip_135x135cm_1997.jpg) 'KadınınFendi (Woman Power)', earthenware, coloured brown slip, 135x135 cm, 1997 / Courtesy of the artist

'KadınınFendi (Woman Power)', earthenware, coloured brown slip, 135x135 cm, 1997 / Courtesy of the artist

'El ağzıileyolacikilmaz', beige stoneware, black glaze by brush, 22x26 cm, 2005 / Courtesy of the artist

'El ağzıileyolacikilmaz', beige stoneware, black glaze by brush, 22x26 cm, 2005 / Courtesy of the artist

I did not retire from my art life. I retired from public service only! Now, I find time to read, explore, travel, learn and design more. I can listen to myself. First of all, I would like to have a retrospective exhibition of my research and art with an accompanying catalogue. In terms of work, I want to continue exploring the beauty of blue as well as undertake some more nature-related studies that depict social events via symbols. As you get older, you understand that thousands of years and more have witnessed the traces of life —trust, eternity, distance or accessibility, etc.— like mountains, for example. And once I realized this, I desire to reach such eternal emotions too.

I would also like to found a comprehensive ceramics museum in Turkey that would exhibit and combine traditional and contemporary ceramic traditions, and find a home for my own body of work.

White Light Diet, 2,5x2,5m, 2006/ Courtesy of the artist<

White Light Diet, 2,5x2,5m, 2006/ Courtesy of the artist<

After graduation, I wanted to learn more about ceramics and art. For this reason, I worked on high-grade ceramics and ceramic technology in Australia. I realized that I wanted to share my experience and knowledge with students and colleagues in the Ceramics Department of a Faculty of Fine Arts at a university established in the middle of Anatolia. I have trained very good students. They have done well at other universities. They work as educators, administrators and artists. I have designed education programs to contribute not only to my students, but also to the field of ceramics more generally.

I am still working to improve the place of contemporary ceramics in Turkey and worldwide. This is why I set up 'Ceramic Art, Education and Exchange'(SSEDD) association in 2013 in Turkey that supports global ceramic education initiatives. Our activities are carried out regularly every year. I still get great pleasure from teaching, learning and doing ceramics. Looking back on the past, I have organized numerous shows, competitions, exhibitions of women's arts and handicrafts, conferences, and demonstrations, written several books and articles, prepared myriad lectures, travelled around the world and made many friends, My life has been full and useful.

_2017.jpg) Mountain, 2017, stoneware, blue coloured slips, transparent glaze, (L. 17x23 cm, R. 15x15 cm), 2017

Mountain, 2017, stoneware, blue coloured slips, transparent glaze, (L. 17x23 cm, R. 15x15 cm), 2017

There are so many things to tell and share, and so I thank Islamic Arts Magazine and its readers for their short entry in my life and art. Thank you.

Comments

Add a comment