ART HISTORY 19th Century Bosnian Calligrapher Sheikh Muhammed Behauddin Sikiric

Jul 06, 2017 Calligraphy

This article is a part of the project 'Promotion of the Ottoman Cultural Heritage of Bosnia and Turkey' which is organized by Monolit, Association for Promoting Islamic Arts and supported by the Republic of Turkey (YTB - T.C. BAŞBAKANLIK Yurtdışı Türkler ve Akraba Topluluklar Başkanlığı / Prime Ministry, Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities).

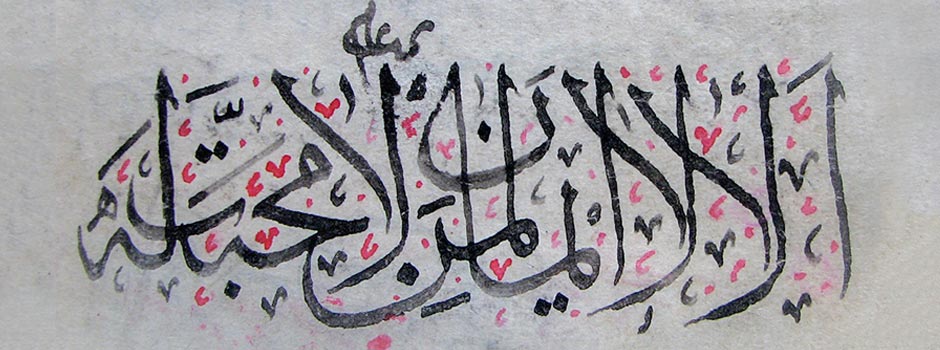

Not much has been written about Muhammed Behauddin Sikiric as a calligrapher. He was born in 1860 in Oglavak, in a family that was high in spiritual education, and the most eminent person from the family was Sheikh Sirri Baba. Behauddin Sikric was educated in Sarajevo where he finished the Merhemi Madrasa and the School for Educators (teachers). He learned calligraphy, first in Bosnia, from Hafiz Hussein Rakim Islamovic, and then continued his studies in Istanbul, as it is said that he had a calligraphy exam in Istanbul in 1911. He taught calligraphy in several schools and madrasas at that time. He signed his work with "Sejh zade-Sehovic," and he also had his seal in the form of a triangle, which included " Es-sejh Behauddin Nuri Naqshibendi " (Muhamed Hadžijamakovic, "The 50th Anniversary of the Death of Behauddin ef Sikiric", in: Glasnik VIS, 6, 1984, 721-725). Behauddin died on September 20, 1934, in Sarajevo.

Fig.1 Fotograph of Sheikh Behauddin Sikiric. Photo courtesy of Dr Meliha Teparic

Fig.1 Fotograph of Sheikh Behauddin Sikiric. Photo courtesy of Dr Meliha Teparic

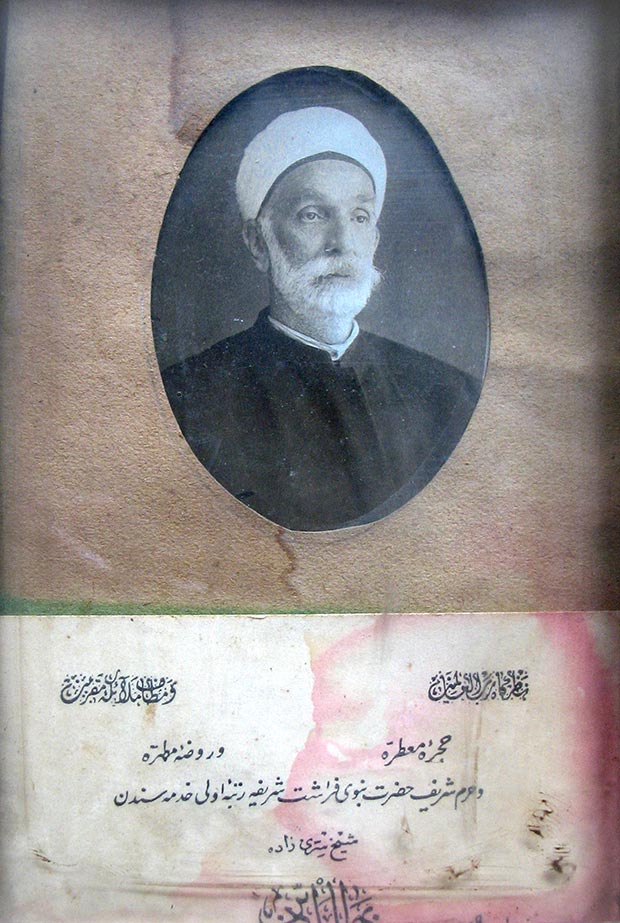

From Sheikh Behauddin there are several calligraphic works preserved: Calligraphic Ijazetnama from the oriental manuscripts collection of the Mesudi Library in Kacuni; The work of Al-'AqÄ'idu'l-islÄmiyyah from the oriental collection of the Bosniak Institute - Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation; transcription of Dala'il al-Khayrat, the photograph of this manuscript is published in the text of Munib Spaho, 'About Islamic Calligraphy in Sarajevo,' in: Blagaj - Islamic Commitment and Bosniak Heritage, 1/1/1997, 82-85, transcription of Kaimi's work 'Varidata' from 1890 (Muhamed Zdralovic, 'Bosnian-Herzegovinian Translators of Works in Arabic Manuscripts I', Sarajevo, Svjetlost, 1988, 144-145); a transcription of three ijazas (R 10315, R 2862 and R 7577), from the oriental collection of the Gazi Husrev Beg Library; several notebooks (medžmua) from the oriental collection of the Bosniak Institute - Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation; and several chronographs for which we believe that Sheikh Behauddin produced the calligraphic designs, and the calligraphic writing for Al-Fatiha, located in the Naqshibendi Tekke in Vukeljici near Fojnica. According to the manuscript of Sheikh Behauddin, Evrad-Behai was printed. (Saicir Sikiric, 'Tekke on Oglavak', in: Gajret - Calendar for 1941, Sarajevo, 1940, 42-51.)

By studying the life of Muhammed Behauddin as a calligrapher, and taking in consideration his family, his study of Arabic calligraphy might have begun early, possibly in his childhood.

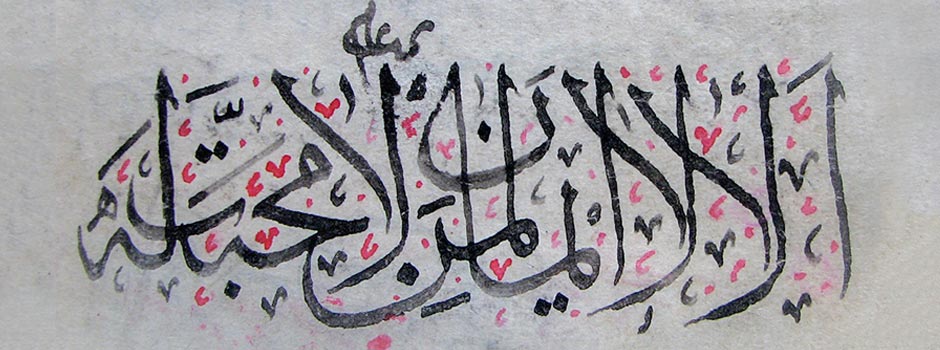

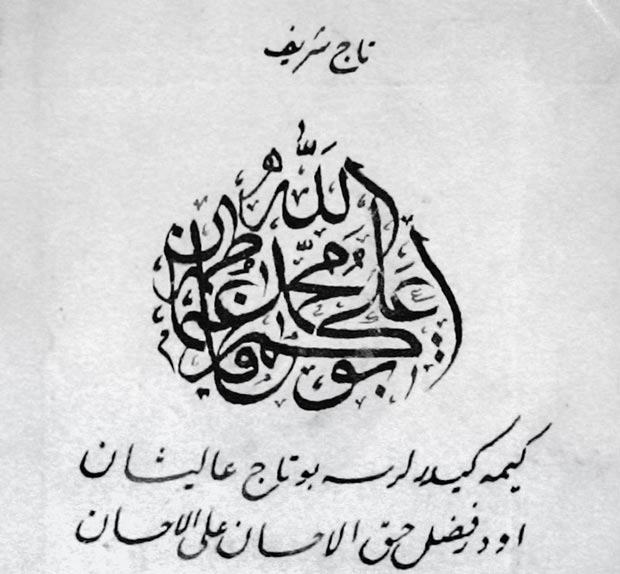

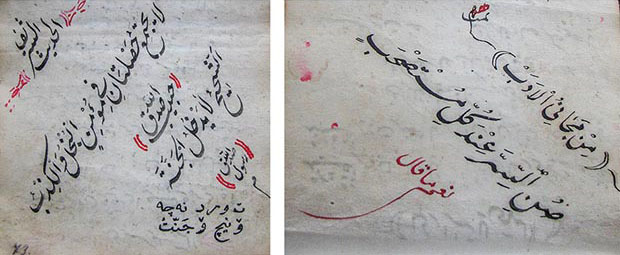

Fig.2 Ijazatnama of Sheikh Behauddin, from the oriental manuscripts collection of the Mesudi Library in Kacuni. Photo courtesy of Mesudi Library

Fig.2 Ijazatnama of Sheikh Behauddin, from the oriental manuscripts collection of the Mesudi Library in Kacuni. Photo courtesy of Mesudi Library

Sikiric was a great Bosnian calligrapher, as the text of his diploma confirms: "He learned fast, so he in a brief time accepted the values of writing by emphasizing his skills (translation of this diploma was published in Meliha Teparic, 'Muhamed Behauddin Sikiric and his Calligraphic Idioms', in Anali Gazi Husev Beg Library, XXXV, 2014, 179 - 202). The diploma also states that he achieved a high title of calligraphy - hattat and that he perfected all the styles (aklam-i sitte) as well as other styles. In ijazatnama it is written: "He has mastered all styles, thuluth, naskh, diwani, riqa, sijaket, rejhani, jeli, kufic, ta'lik, tughra, sinjir, and God alone knows what he has mastered."

Sikric probably went to Istanbul as a calligrapher, and continued his further training in calligraphy, in order to obtain a calligraphic diploma in Istanbul in 1911. (Gacanovic, Emir Sejh Siri baba, Fojnica: Nepoznata Bosna, 2014, 106)

It is indisputable that during his stay in Istanbul Sheikh Behauddin had an opportunity to see, on a daily basis, the most valuable examples of calligraphy artworks in various mosques, tekke, and other sacred and profane monuments, which affected his artistic talent and taste. Since it is not known with whom he improved his calligraphy in Istanbul, Behauddin most certainly met with contemporaries, living masters of calligraphy such as: Sami Efendi (d.1912), Mehmed Nazif Bey (d.1913); Mehmed Fehim Efendi (d.1914), Hasan Riza Efendi (d.1920), Omer Vasfi (d.1928), Mehmed Abdulaziz Efendi (d.1934) and others.

The published notes on Behauddin inform us that he mostly used ta'liq, nesta'liq, and naskh style (Hadžijamaković, 724), however, his manuscripts that have been preserved to this day show that, in addition to the above mentioned styles of Arabic script, he often used also thuluth and riqa. It is possible that levhas (calligraphic panels) were mostly written in ta'liq style.

The well known chronogram by Behauddin (Sikiric, 50-51) is the Sheikh Sakir Rasim's tombstone. The calligraphy, in ta'liq style, is relatively well executed. The inscription leads us to believe that Behauddin, in addition to composing the chronograms, probably also developed a calligraphic design for the same. Considering that the stone is exposed for centuries to different weather conditions which might have caused the destruction of the surface of the tombstone and distorted appearance of the letters. The most interesting are smaller inscriptions and compositions that are found on some parts of the tombstone, such as inscriptions that read Hu, Ja Hakk and others. The tombstone, with the accompanying Sufi iconography and characteristic turban, is quite striking.

Fig.3-5 L_Photo of Sheikh Sakir's tombstone. Photo by Sahar Kuhen / R_Details of inscriptions Hu and Ja Hakk. Photo by Cazim Hadzimejlic

Fig.3-5 L_Photo of Sheikh Sakir's tombstone. Photo by Sahar Kuhen / R_Details of inscriptions Hu and Ja Hakk. Photo by Cazim Hadzimejlic

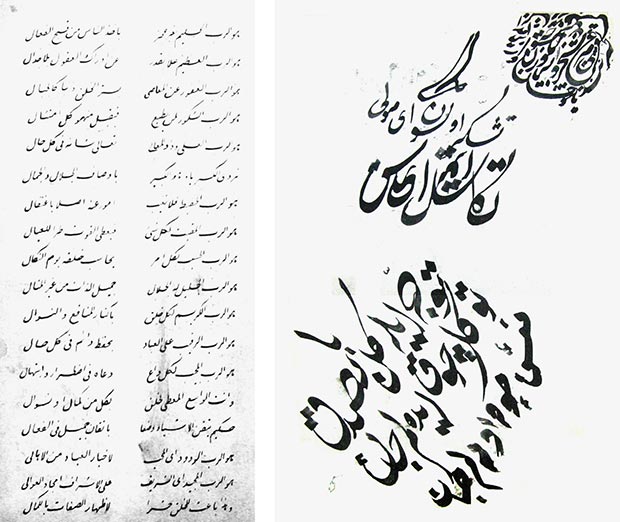

From Behauddin's other works, several of his handwritten notebooks are preserved. One notebook was in possession of Sheikh Behauddin efendi Hadzimejlic, the second notebook was in possession of late professor Seid Strik, and two more are a part of the collection of oriental manuscripts of the Bosniak Institute - Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation (Ms 382 and Ms 371).

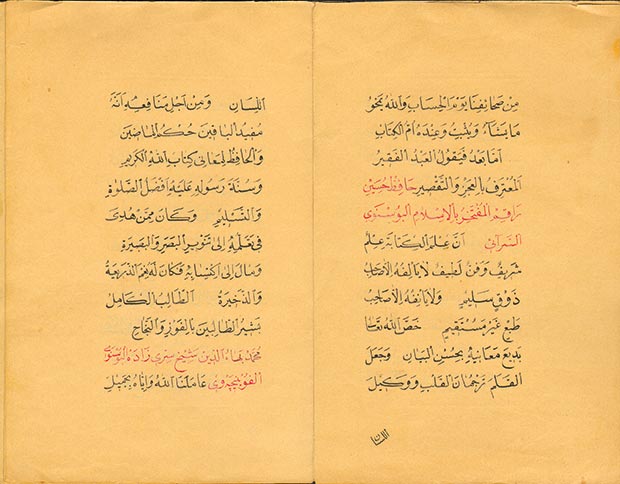

The mentioned notebooks are written in several different styles of Arabic script, which is precious to us as his other calligraphic works are not known. Thus, in these notebooks we find small calligraphic compositions (istif), as they are penned with a large pen, in the form of levha.

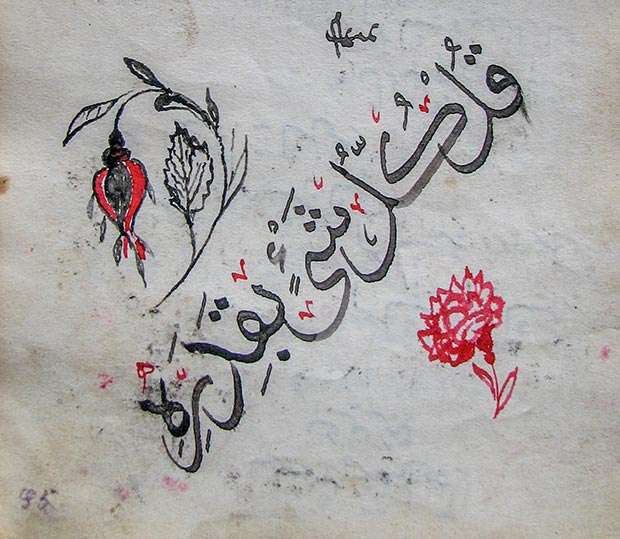

Fig. 6 From the notebook of late professor Seid Strik. Photo by Meliha Teparic

Fig. 6 From the notebook of late professor Seid Strik. Photo by Meliha Teparic

Fig. 7 From the notebook of late professor Seid Strik. Photo by Meliha Teparic

Fig. 7 From the notebook of late professor Seid Strik. Photo by Meliha Teparic

In his notebook, in addition to the usual writing in horizontal rows, Behauddin introduced the accompanying smaller or larger writings which in a certain way represent his artistic calligraphy compositions often found on levhas. Perhaps we could say that they are a kind of a sketch that partially illuminates or illustrates what kind of calligraphic panels (levhas) were created by Behauddin.

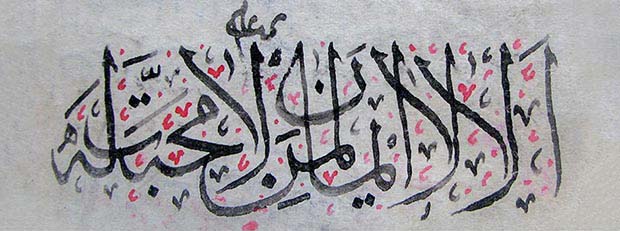

Fig 8 Details of thuluth style from the notebook (Ms 382, The Bosniak Institute – Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation). Photo courtesy of The Bosniak Institute – Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation

Fig 8 Details of thuluth style from the notebook (Ms 382, The Bosniak Institute – Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation). Photo courtesy of The Bosniak Institute – Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation

Fig 9 Details of thuluth style from the notebook (Ms 382, The Bosniak Institute – Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation). Photo courtesy of The Bosniak Institute – Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation

Fig 9 Details of thuluth style from the notebook (Ms 382, The Bosniak Institute – Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation). Photo courtesy of The Bosniak Institute – Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation

Calligraphic writings, especially those presented on the photographs 8 and 9, represent the type of calligraphic composition called istif. Thus, these examples represent harmoniously composed units that could serve as a sketch for a larger jeli pen, or levha. Given the character and purpose of the manuscript, these small inscriptions are artistically very well developed, as they testify to maturity of the calligrapher and his experience in creating compositions.

In addition to the usual black ink used by calligrapher Behauddin, the red ink is also mentioned in the diploma: "... and the red ink of his pen he left on whiteness of the pages." Thus, notebooks contain examples of scripts penned by red ink, which is used more or less for the writing of diacritical signs and certain sentences. In addition to the calligraphic writings, there is obvious tendency towards floral decoration, and perhaps we can assume that his levhas have been decorated with similar motifs.

Although in the notebook there are various examples of his artistic mastery, the parts penned in ta'liq style are extremely fine and created with a lot of attention, which confirms that his calligraphic expression was mostly perfected in ta'liq script where a high dose of precision, concentration, and delicacy is noticeable. As a result, these are examples of calligraphy with the highest degree of elegance and sophistication, although these patterns are certainly not his most representative works, as it could be expected on his larger compositions - levhas.

A good example of Sikric's calligraphy in ta'liq script can also be found in the notebook from the Bosniak Institute (Ms 382) originating from the Sikirić family, from Oglavak near Fojnica.

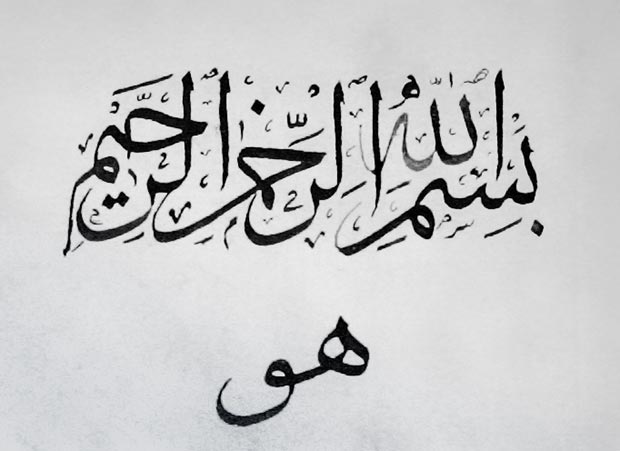

Fig. 10-11 Details of ta'liq style from the notebook of late professor Seid Strik. Photo by Meliha Teparic

Fig. 10-11 Details of ta'liq style from the notebook of late professor Seid Strik. Photo by Meliha Teparic

L_Fig. 12 Detail from the notebook (Ms 382, The Bosniak Institute –Adil Zulfikarpasic Fondation) / R_Fig. 13 The page from the manuscript (Ms 385), informal writing with a visible combination of three styles: ta'liq, diwani and riqa'. The Bosniak Institute – Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation / Photo courtesy of The Bosniak Institute – Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation

L_Fig. 12 Detail from the notebook (Ms 382, The Bosniak Institute –Adil Zulfikarpasic Fondation) / R_Fig. 13 The page from the manuscript (Ms 385), informal writing with a visible combination of three styles: ta'liq, diwani and riqa'. The Bosniak Institute – Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation / Photo courtesy of The Bosniak Institute – Adil Zulfikarpasic Foundation

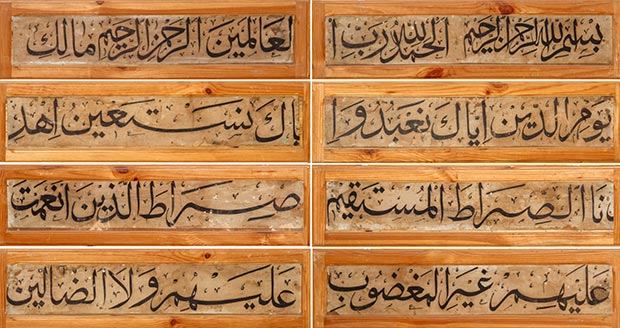

In the Naqshibendi Teki 'Pir-i Sani Husein-babe' in Vukeljici several calligraphic panels are attributed to Behauddin Sikiric, and are protected by the Commission for the Preservation of the National Monuments. On the wooden dome's ring there is Surah Al-Fatiha written with jeli thuluth (large) script in 8 rectangular parts, and all of the writings on paper were later probably laminated on a wooden base. There is no signature, so the year of creation is not known. By analyzing these inscriptions, it is evident that the work was probably done on a single paper or on a pair of larger units. In a later conservation, probably when laminating on wood, the work was divided into 8 parts. Unfortunately, due to unprofessional conservation, work was poorly cut so that individual letters or words do not run to the end. As for the script itself, this Sikiric's work could be dated as his early period. Letters give the character of hardness, and the pen is quite wide in proportion to the letters, so the curved parts of the letters are somewhat sharper at the transitions from the vertical to the horizontal, etc. While the examples of thuluth style found in the notebooks have much more delicate proportions and transitions. All these inscriptions in thuluth have a lot of similarities in their execution. Based on that, we are inclined to believe that these works belong to the early, rather than the mature Sikric period. The calligraphic works by Sheikh Behauddin that have been discovered so far, are the only testimony to his artistic work. Partially visible are his calligraphies from the found notebooks, with the compositions in thuluth and ta'liq style. From these clippings, it can be concluded that Sheikh Muhammed Behauddin Sikiric was an outstanding calligrapher. By comparing examples of thuluth style in the notebooks with calligraphic panels from the Teke in Vukeljici, it is noticeable that Sikric had a somewhat thicker, or wider pen, which was obviously characteristic in this calligraphic style of the Arabic script. Better examples written in ta'liq style emanate with special energy and feeling. The proportions of the letters, the trace of the pen, the harmony, the elegance, the sophistication, all contribute to the quality of his work. Since these works are not even the most representative examples of his calligraphic achievements, it can be assumed that his calligraphic panels, mentioned in various sources, were at a high level of aesthetics of the calligraphic art. It is a great loss for the art of Islamic calligraphy in Bosnia, that it is unknown where Behudin Sikric's levhas are located, as they certainly exist in private collections. Fig. 14 Al-Fatiha in the dome's ring at the teki Pir'i Sani Husein-baba in Vukeljici. Photo by Sara Kuehn

Fig. 14 Al-Fatiha in the dome's ring at the teki Pir'i Sani Husein-baba in Vukeljici. Photo by Sara Kuehn

Comments

Add a comment